| Windows on the World | |

|---|---|

Logo designed by Milton Glaser |

|

|

|

| Restaurant information | |

| Established | April 19, 1976; 47 years ago |

| Closed | September 11, 2001 (destroyed in September 11 attacks) |

| Previous owner(s) | David Emil |

| Head chef | Michael Lomonaco |

| Street address | 1 World Trade Center, 107th Floor, Manhattan, New York City, NY, U.S. |

| City | New York City, New York |

| Postal/ZIP Code | 10048 |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 40°42′44″N 74°0′47″W / 40.71222°N 74.01306°W |

| Seating capacity | 240 |

| Website | windowsontheworld.com (archived) |

Windows on the World was a complex of dining, meeting, and entertainment venues on the top floors (106th and 107th) of the North Tower (Building One) of the original World Trade Center complex in Lower Manhattan.[1]

It included a restaurant called Windows on the World, a smaller restaurant called Wild Blue[1] (before 1999 was called «Cellar in the Sky»), a bar called The Greatest Bar on Earth[1] (which had previously been the Hors d’Oeuvrerie[2]) as well as a wine school and conference and banquet rooms for private functions located on the 106th floor. Developed by restaurateur Joe Baum and designed initially by Warren Platner, Windows on the World occupied 50,000 square feet (4,600 m2) of space in the North Tower. The Skydive Restaurant, which was a 180 seat cafeteria on the 44th floor of 1 WTC conceived for office workers, was also operated by Windows on the World.[3][4]

The restaurants opened on April 19, 1976, and were destroyed in the September 11 attacks.[5][6] All of the staff members who were present in the restaurant on the day of the attacks perished; escape was impossible from the 92nd floor or higher.[7]

Operations[edit]

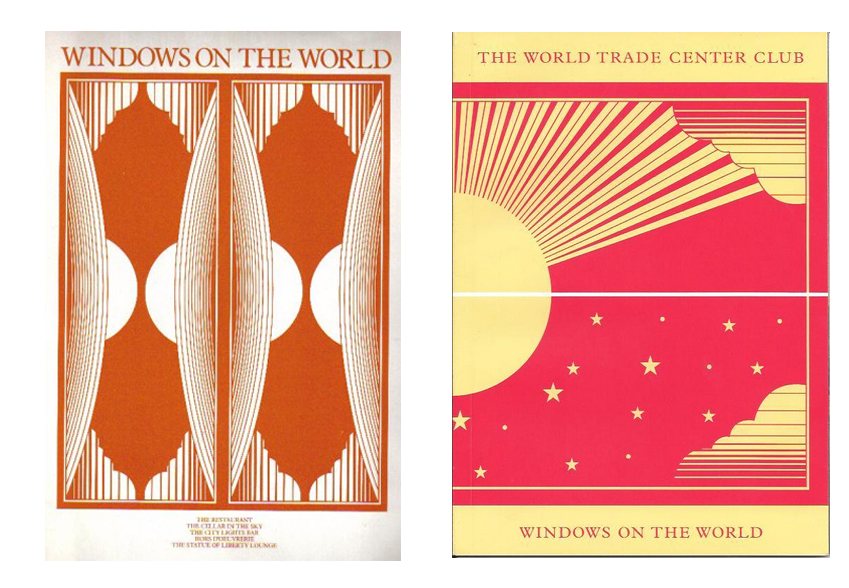

The main dining room faced north and east, allowing guests to look out onto the skyline of Manhattan. The dress code required jackets for men and was strictly enforced; a man who arrived with a reservation but without a jacket was seated at the bar. The restaurant offered jackets that were loaned to the patrons so they could eat in the main dining room.[8] The dinnerware, rugs, lighting fixtures, menus and the communication equipment were designed by Milton Glaser.[9][10][11]

A more intimate dining room, Wild Blue, was located on the south side of the restaurant. The bar extended along the south side of 1 World Trade Center as well as the corner over part of the east side. Looking out from the bar through the full length windows, one could see views of the southern tip of Manhattan, where the Hudson and East Rivers meet. In addition, one could see the Liberty State Park with Ellis Island and Staten Island with the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. The kitchens, utility spaces, and conference center in the restaurant were located on the 106th floor.

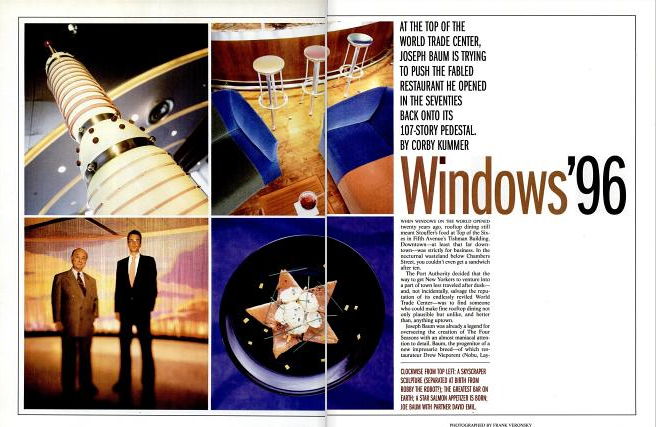

Windows on the World closed after the 1993 bombing, in which employee Wilfredo Mercado was killed while checking in deliveries in the building’s underground garage. The explosion also damaged receiving areas, storage and parking spots used by the restaurant complex.[12] On May 12, 1994, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey announced that the Joseph Baum & Michael Whiteman Company had won the contract to run the restaurants after Windows’s former operator, Inhilco, gave up its lease.[13] It underwent a US$25 million renovation and reopened in June 26, 1996.[14][15] Cellar in the Sky, which was a different space within the restaurant (it could only seat 60 people), reopened after Labor Day.[16] In 1999, Cellar in the Sky was changed into an American steakhouse and renamed «Wild Blue».[17] In 2000, its final full year of operation, it reported revenues of US$37 million, making it the highest-grossing restaurant in the United States.[18]

The executive chefs of Windows on the World included Philippe Feret of Brasserie Julien while the last chef was Michael Lomonaco.

September 11 attacks[edit]

Windows on the World was destroyed when the North Tower collapsed during the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. While the restaurant was hosting regular breakfast patrons and the Risk Waters Financial Technology Congress, Egyptian terrorist Mohamed Atta and four other Al-Qaeda hijackers crashed American Airlines Flight 11 into the North Tower between floors 93 and 99 at 8:46 a.m.[19] Everyone present in the restaurant died that day, as all means of escape (including the stairwells and elevators leading down from the impact zones) were instantly severed by the impact. Victims trapped in Windows on the World either died from smoke inhalation from the ensuing fire, jumping or falling to their deaths from the restaurant, or being killed in the eventual collapse of the North Tower 102 minutes later at 10:28 A.M. At least five Windows occupants were witnessed jumping or falling to their deaths from the restaurant.[20]

There were 72 restaurant staff present in the restaurant, including assistant general manager Christine Olender, whose desperate calls to Port Authority police represented the restaurant’s final communications.[21] Sixteen Incisive Media-Risk Waters Group employees, as well as 76 other guests/contractors, were also present.[22] Among those also present was the executive director of the Port Authority, Neil Levin, who was having breakfast. After about 9:40 a.m., no further distress calls from the restaurant were made. The last people to leave the restaurant before Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower at 8:46 a.m. were Michael Nestor, Liz Thompson, Geoffrey Wharton, and Richard Tierney, who all shared an elevator together. They departed at 8:44 a.m. and survived the attack.[23]

World Trade Center lessor, Larry Silverstein, was regularly holding breakfast meetings in Windows on the World with tenants as part of his recent acquisition of the Twin Towers from the Port Authority, and was scheduled to be in the restaurant on the morning of the attacks. However, his wife insisted that he had to go to a dermatologist’s appointment that morning,[24] whereby he avoided death.

Critical review[edit]

In its last iteration, Windows on the World received mixed reviews. Ruth Reichl, a New York Times food critic, said in December 1996 that «nobody will ever go to Windows on the World just to eat, but even the fussiest food person can now be content dining at one of New York’s favorite tourist destinations.» She gave the restaurant two out of four stars, signifying a «very good» quality rather than «excellent» (three stars) or «extraordinary» (four stars).[25] In his 2009 book Appetite, William Grimes wrote that «At Windows, New York was the main course.»[26] In 2014, Ryan Sutton of Eater.com compared the now-destroyed restaurant’s cuisine to that of its replacement, One World Observatory. He stated, «Windows helped usher in a new era of captive audience dining in that the restaurant was a destination in itself, rather than a lazy byproduct of the vital institution it resided in.»[27]

Cultural impact and legacy[edit]

Windows of Hope Family Relief Fund was organized soon after the attacks to provide support and services to the families of those in the food, beverage, and hospitality industries who had been killed on September 11 in the World Trade Center. Windows on the World executive chef Michael Lomonaco and owner-operator David Emil were among the founders of that fund.

It has been speculated that The Falling Man, a famous photograph of a man dressed in white falling headfirst on September 11, was an employee at Windows on the World. Although his identity has never been conclusively established, he was believed to be Jonathan Briley, an audio technician at the restaurant. Jonathan was the younger brother of Alex Briley, the original «G.I.» from the band Village People .[28]

On March 30, 2005, the novel Windows on the World, by French novelist Frédéric Beigbeder, was released. The novel focuses on two brothers, aged seven and nine years, who are in the restaurant with their dad Carthew Yorsten. The novel starts at 8:29 a.m. (just before the plane hits the tower) and tells about every event on every following minute, ending at 10:30 a.m., just after the collapse. Published in 2012, Kenneth Womack’s novel The Restaurant at the End of the World offers a fictive recreation of the lives of the staff and visitors at the Windows on the World complex on the morning of September 11.

On January 4, 2006, a number of former Windows on the World staff opened Colors, a co-operative restaurant in Manhattan that serves as a tribute to their colleagues and whose menu reflects the diversity of the former Windows’ staff. That original restaurant closed, but its founders’ umbrella organization, Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, continues its mission, including at Colors restaurants in New York and other cities.

Windows on the World was planned to reopen on the top floors of the new One World Trade Center, when the tower was complete. However, on March 7, 2011, it was cancelled because of cost concerns and other troubles finding support for the project.[29] Instead, One World Observatory contains eateries named ONE Dine, ONE Mix and ONE Café.[30]

See also[edit]

- List of tenants in 1 World Trade Center (1971–2001)

- Top of the World Trade Center Observatories

References[edit]

- ^ a b c «Fine Dining, Eateries/Specialty Foods». Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on June 9, 2001. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ Morabito, Greg (September 11, 2013). «Windows on the World, New York’s Sky-High Restaurant». Eater NY. New York City. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ Grimes, William (September 19, 2001). «Windows That Rose So Close To the Sun». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 17, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Roston, Tom (2019). The Most Spectacular Restaurant in the World: The Twin Towers, Windows on the World, and the Rebirth of New York. New York City: Abrams Books. ISBN 978-1-4197-3799-2. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ «Trade Center to Let Public In for Lunch At Roof Restaurant». New York Times. April 16, 1976. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

- ^ Windows ’96. New York City: New York Magazine. July 15, 1996. pp. 42–47. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ «Windows That Rose So Close To the Sun». The New York Times. September 19, 2001. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ Chong, Ping (2004). The East/West Quartet. Theatre Communications Grou. p. 143. ISBN 9781559362290.

- ^ «CASE STUDY # 12 Windows on the World». miltonglaser.com. New York City. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ «The Work — Windows on the World». miltonglaser.com. New York City. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ «Milton Glaser’s menus for the World Trade Center». New York City: SVA Archives. January 25, 2014. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Fabricant, Florence (September 22, 1993). «A New Era for Windows on the World». The New York Times. New York City. p. 10. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Bryan (May 13, 1994). «Familiar Face Behind New ‘Windows’«. The New York Times. New York City. p. 3. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ Roca, John (June 26, 1996). «Opening of Windows of the World restaurant in the World Trade Center». Getty Images. New York City. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ «New Windows on a New World;Can the Food Ever Match the View?». The New York Times. June 19, 1996. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ Siano, Joseph (June 23, 1996). «TRAVEL ADVISORY;World Trade Center Restaurant to Reopen». The New York Times. New York City. p. 3. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ Grimes, William (June 9, 1999). «RESTAURANTS; In a Cozy Cabin Amid the Shooting Stars». The New York Times. New York City. p. 8. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ The Wine News Magazine Archived 2012-02-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Risk Waters Group World Trade Center Appeal».

- ^ National Institute of Standards and Technology (2005). «OBSERVATIONS OF FALLING HUMAN BEINGS FOR WTC 1» (PDF).

- ^ «‘We need to find a safe haven,’ WTC restaurant manager pleads». USA Today. August 28, 2003. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ «Risk Waters Group archived home page». Archived from the original on August 2, 2002.

- ^ «9/11: Distant voices, still lives (part one)». The Guardian. London. August 18, 2002. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- ^ «Larry Silverstein: Silverstein Properties». New York Observer. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ Reichl, Ruth (December 31, 1997). «Restaurants; Food That’s Nearly Worthy of the View». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Grimes, William (October 13, 2009). Appetite City: A Culinary History of New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-42999-027-1.

- ^ Sutton, Ryan (June 30, 2015). «Everything You Need to Know About Dining at One World Trade». Eater NY. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Henry Singer (director) (2006). 9/11: The Falling Man (Documentary). Channel 4.

- ^ Feiden, Douglas (March 7, 2011). «Plans to build new version of Windows on the World at top of Freedom Tower are scrapped». New York Daily News. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ «One Dine». One World Observatory. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

External links[edit]

- Windows on the World (Archive)

- Archived snapshot of the former WotW website, August 2, 2002

- Last pre-9/11 archived snapshot of the former WotW website, February 1, 2001

- Photographs of WotW

The Windows On The World restaurant located in the North Tower of the WTC demonstrated how life and death can sometimes be decided on a razor thin wire of chance. In rare cases, one small change to a persons circumstances can significantly change the course or outcome of an event. The details of this decision-incident can often remain completely hidden to all the individuals involved until the event is completely over. Only then does the clear picture begin to unfold.

WTC North Tower – September 11th – Slim Chance Between Life and Death.

In this terrible tragedy, the North Tower, also known as 1 World Trade Center had it the worst. Not only was it the first building to be hit by one of the planes, but it was also the last building to fall. It was the only building that had all its fire stairs knocked out, that meant no-one above air strike on the 92nd floor ever got out and there would be no escape for its trapped occupants, where they would forced to witness the increasing carnage around them with their own slow realization of their ultimate demise.

The Hijacked Planes Strike

On September 11th 2001 at 8:46:26 a.m. American Airlines Flight 11 Boeing 767 impacted the north side of the North Tower of 1 World Trade Center. The plane entered the North Tower between the 94th and 98th floors. Flight 11 was flying at a speed of 490 miles per hour at the time of impact. North Tower occupants had no clue what was about to happen and they had no chance of survival from above the impact site, because, unlike the South Tower that was hit a few minutes later, all the fire escapes were destroyed by the impact of the plane. Documented accounts of human losses that morning at the North Tower at The World Trade Center included employees from such companies as Aon Corp, Cantor Fitzgerald and Marsh & McLennan. One particular company, Risk Waters Group Ltd, A British company, was at The Windows On The World conference facility that morning, they would not normally have been there.

Windows On The World – Background On This Most Famous Restaurant

Windows On The World was a world famous 40,000 square foot restaurant near the top of the North tower on the 107th Floor at 1 World Trade Center. It boasted a popular “New American” style menu and had a first class wine list that included Chateau Lafite-Rothschild 1928 for $3000.00. The 107th floor was also occupied by “The Greatest Bar on Earth”, aka GBOE. This 13,000 square foot happy hour bar was popular with tourists and Wall Street types alike. It was a traditional for New Yorkers to often complain about its “poor quality” and “expensive” drinks, but its location spoke volumes with amazing panoramic views of Manhattan and the tri-state area that was pretty hard to beat. The 107th floor was also occupied by Wild Blue, a romantic and quieter restaurant and bar in the space formerly occupied by Cellar in the Sky. A popular misconception is that Windows on the World was at the very top of the North tower, when in fact the top enclosed floor was the 110th floor, where CNN and some other television companies sited equipment and staff.

The South tower, across the square, was home to the public glass-enclosed observatory located on the 107th floor and the world’s highest open-air deck on the 110th floor, that the tourists could visit. On the fateful day of 9/11 2001 the Windows on The World Conference Facility on the 106th floor was playing host to the Risk Waters Financial seminar. One floor above, on the 107th floor, the main restaurant and the bar were closed. Wild Blue, however was the only thing open on that floor and was serving breakfast to a number of WTC tenants and occupants.

The Risk Waters Financial Conference

The Risk Waters Group would not have normally been at the World Trade Center that day. They had organized a financial technology conference that was due to run both days of Tuesday 11th and Wednesday 12th of September 2001. They had invited a number of delegates from various financial companies and vendors in New York and the United States. What distinguishes those delegates from the other victims in the WTC is that they wouldn’t normally be there and chance had a way of putting them there that morning. This, of course, is of no solace to the families left behind, but nevertheless remains a gruesome fact. The delegate’s presence at the WTC is somewhat akin to the people who died at the (alleged) job interviews at Cantor Fitzgerald on the 95th floor. People who wouldn’t have normally been there, but happenstance put them there.

The Risk Waters conference was due to start at 8:00 AM with Breakfast, with the first speaker due to begin at 9:00 AM.At the precise time of the impact were 16 staff from Risk Waters and 53 delegates from various invited companies and vendors in attendance. An additional 137 delegates had been invited but had not arrived at the time of the impact or did not plan in coming after all. Following the plane impact there were reports that delegates from this conference were being moved to the 107th floor. Conflicting reports indicate that smoke was heavy at the 107th floor and all the “Windows” staff was moved to the 106th floor to join the delegates.

No Survivors From Above The 92nd Floor

Other people above the impact site in the North Tower included staff from Windows on the World located on the 106th and 107th floors and from other companies on various floors above and below. It is understood that the roof deck was not accessible by the staff and delegates, but this is perhaps irrelevant as they may have sought adequate refuge on the 106th floor and rooftop rescue by helicopter was not a viable option, due to the updraft caused by the burning aviation fuel

It is estimated over 200 people jumped to their death, with the majority of that number being made up from the North tower, where the fire and smoke were limited to fewer floors – which made it more intense. The estimate was because “Jumper” injuries were very similar to injuries sustained by enclosed occupants and could not be clearly established following the event. The figure was arrived at by analyzing photographs of descending bodies that were taken at the scene.

In the North Tower there were 1360 fatalities above the 92nd floor, which was 100% of its occupants at the time.In contrast, the South tower had one fire escape that was passable after their impact, so in fact 350 people escaped even though they were above the point of impact.Being above the 92nd floor in the North tower on that fateful day meant certain death for its occupants. No one survived.

While many WTC corporations knew the risk of an attack following the 1993 bomb was high, they had accepted the risk of this occurrence and went on with their daily lives. In retrospect all the regular daily inhabitants of the WTC were a walking probability. The Risk Waters group and delegates exemplify the randomness of the event. It seems sadly ironic that the Risk Waters Group range of products and services are dedicated to risk management.

Individuals of Special Note Who Died in the North Tower

Liz Thompson, executive director of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council

Liz Thompson 61 is executive director of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (LMCC). Thompson was on what was to be the last elevator down from the 91st floor in the north tower of the World Trade Center. She was in a meeting concerning a public art commission; Liz is reported to have exited the lobby at 8:43 AM. LMCC artist in residence Michael Richards, was not so lucky, he remained on the 91st floor and perished.

George Sleigh, naval architect

62-year old naval architect, George Sleigh, was in a north-facing office on the telephone to a colleague on the 91st floor. Incredibly, George witnessed the aircraft heading towards his building when it was just two to three plane lengths away. “It was quite a shock to see a large passenger plane that close to the building. Almost immediately upon me seeing it, the plane hit the building,” he says. George works for the American Bureau of Shipping; its suite of offices was on the 91st floor, immediately to the left of the impact zone. It took George 50 minutes to descend the 91 flights to safety within a northern stairwell. He remains the highest survivor from the North Tower, no others from his floor (or above) survived

Peter Field, the chairman and chief executive of Risk Waters Group

Peter Field, the chairman and chief executive of Risk Waters Group, was scheduled to be at the Risk Waters conference that morning. He recalls, “I was up at about 6:30am to check my e-mail and phone the London office, intending to leave for the inaugural Waters Financial Technology Congress at the World Trade Center no later than 8:00 am. But I had trouble retrieving my e-mail and I decided to call our IT manager in London to get the problem sorted out. It was this simple act that probably saved my life. By the time I’d accessed my e-mail, I was running late, eventually leaving my hotel on the Upper West Side at about 8:10am. I ran across the road from my hotel to the 66th St. subway entrance only to find there was a long delay in the service on the 1 and 9 lines to the Cortlandt St./World Trade Center station. Eventually, I crammed myself on to a train at around 8:25am. I thought: “I might still catch David’s opening remarks because the conference is bound to start a little late.” Delegates always register at the last minute on the first day of conferences. David Rivers, our company’s editorial director in New York, knew more about financial technology than many in the industry and was therefore ideal to open the first Waters Congress at Windows on the World, on the 106th floor of the north tower of the World Trade Center”When Peter arrived at street level at Cortlandt St at 8:50am he found the tragedy beginning to unfold “There was a sickening smell of what I thought was gas but which I later discovered was jet fuel”. ” On the shopping concourse above the station, I remember a brief glimpse of broken glass and a cacophony of alarms before I became aware of security guards screaming at us, “Run, run for your life””.

Greg Manning, Trader at Euro Brokers

Greg Manning who stood, horrified, on the morning of Sept. 11 as he watched the towers burn – smoke belching, he was certain, from the 105th floor of Tower One, where his wife Lauren worked, and the 84th floor of Tower Two, where his employer, Euro Brokers, was located. Friends and family called immediately. “I could not say whether Lauren was alive,” Greg Manning wrote in his book. “I was almost certain she was dead.” Behind schedule that day, Greg, a Euro Brokers vice president, was to have attended the Risk Waters conference at the Windows on the World on the 106th floor of Tower One.

Tony Mann, President of E-J Electric

Tony Mann, president of E-J Electric, Long Island City, which had an office in Tower 2, built and maintained the World Trade Center’s entire security system. On the morning of Sept. 11, the electricians were doing routine maintenance work when the first hijacked commercial airliner slammed into Tower 1.”Five minutes before it happened, one of our foremen was on the 107th floor,” Mann said. “His radio wasn’t working, so he came down and was walking across the lobby when the first plane hit. He then ran down to the basement to make sure all our people got out.”

Rick Weisfeld, President of Bronx Builders

For Rick Weisfeld, president of Bronx Builders, a woodworking firm, the morning was especially hard. Three of his employees were in the World Trade Center, attending an early morning meeting at Windows on the World on the 107th floor “We were renovating one of the bars there,” Weisfeld recalled. Later, he would learn that all three, including one a key foreman and a close friend, were among the nearly 3,000 people who were killed in the World Trade Center attacks. Architect Obdulio Ruiz-Diaz, a draftsman with Bronx Builders, was one of those men with co-workers Joshua Poptean and Manuel DaMota.

Chris Morrison (34) of Zurich Scudder Investments

Chris Morrison (34) of Zurich Scudder Investments, grew up on High Plain Road, Andover, New York – where his parents – Joe and Maureen – still live. Chris was a popular and successful graduate of Central Catholic High School and St. Lawrence University. He was another delegate attending the Risk Waters seminar on the 106th floor.

Heather Ho, executive pastry chef at New York’s Windows on the World restaurant

Heather Ho, age 32 was an executive pastry chef at New York’s Windows on the World restaurant on the 107th floor of the World Trade Center. Heather was always early for her job and worked hard. She was greatly admired for creative new ideas in the approach to traditional recipes. Her dream was to open her own pastry shop. A roommate described her as a unique and amazing person. She said she knew how to have a good time and also worked and played hard.

Neil D. Levin, Executive Director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

Neil D. Levin, executive director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, wanted the agency’s airports to be showcases for the region, and pushed workers to develop high-tech improvements for airline passengers and time-deprived commuters. He was on the 106th floor talking with his secretary on the 67th floor of the North Tower. It is unclear why he was at

the Risk Waters meeting, as it was primarily for the financial community and no other meetings were taking place on that floor that morning. His wife, Christy Ferer, an author and former television reporter said “The last time someone talked to him, he was on the 106th floor. His secretary [from his office on the 67th floor] was talking to him by phone, and as he was talking the plane hit, and they both said `Holy cow!’ at the same time. The line went dead. Then [a co-worker] said she ran into someone who said he was on the 63rd floor, and that’s what gave me false hope.” “He never returned home”

The Final Messages To Loved Ones

The final messages to the loved ones came in a variety of ways from Windows on the World. Some came via email, others by Blackberry, some managed to use land lines or mobile phones. Some accounts have faxes and others have cherished voicemail’s. By all reports the mobile phone network survived right up until the last minute because the primary transmitter was on the roof, albeit severely impaired by the volume of calls being placed throughout downtown Manhattan. When the final messages were being delivered through the various means, those who were trapped had no chance of survival, they just didn’t know it, neither did anyone else. It was assumed that they had a fighting chance, a slim opportunity to survive, surely someone would survive the dreadful tragedy.

Brian Clark, a World Trade Center survivor in the 1993 and 2001 incidents said in his book “Why couldn’t there have been just one survivor from the North Tower above the impact site? – With a parachute or something, I know it sounds absurd, just so we can say one person survived” He added “Perhaps that individual would have been vilified by grieving families, or maybe it would have brought hope of man’s ability to endure however hopeless the odds”, “To see him jumping out of the building and gliding down in bright colors framed with the beautiful blue sky amid the terrible turmoil of the scene would have raised the hearts of both the trapped and the grieving families alike”, “It’s not their son, but he would have carried the spirit of all of them” “If that had been me, I can’t imagine how I would have been able to turn my back on those left behind though”

With hindsight, many opportunities to avoid being caught up in this terrible tragedy existed, but who was to know such a terrible thing could happen on such a beautiful day. It seems that the odds of the event occurring remained constant and that time was the only unknown factor. This adds weight to the probability argument that, given time, everything can happen to everyone, everywhere. This single event has forever changed the way Americans live their lives, unlike any other single event in modern US history, save for Pearl Harbor and D-Day.

The tenants above the 91st floor of the North Tower at the World Trade Center were:

| Organizations Above 91st Floor 1 WTC — North Tower | Floor |

|---|---|

| American Bureau of Shipping | 91 |

| Lower Manhattan Cultural Council | 91 |

| Carr Futures | 92 |

| Fred Alger Management | 93 |

| Marsh USA | 93 -100 |

| Kidder Peabody & Co. | 101 |

| Cantor Fitzgerald Securities | 101-105 |

| The Nishi-Nippon Bank Ltd. | 102 |

| Channel 4 (NBC) | 104 |

| Windows on the World Rest. | 106-107 |

| Greatest Bar on Earth | 107 |

| World Trade Club | 107 |

| Channel 5 (WNYW) | 110 |

| Channel 31 (WBIS) | 110 |

| Channel 47 (WNJU) | 110 |

| Channel 2 (WCBS) | 110 |

| Channel 11 (WPIX) | 110 |

| CNN | 110 |

25 Photos Of Windows On The World, From Its ‘Spectacular’ Beginnings To Its Tragic Destruction On 9/11

Published September 9, 2023

Updated September 11, 2023

Windows on the World opened in April 1976 to critical acclaim — and by 2000 it was the top-grossing restaurant in the U.S.

1 of 26

Employees work to set up tables at the restaurant. Instagram

2 of 26

A woman lights a man’s cigarette at Windows on the World. 1976. Nestlé Library

3 of 26

A bustling day at Windows on the World. Reddit

4 of 26

The stunning view of New York City from Windows on the World. Reddit

5 of 26

A table with a view of the city.Instagram

6 of 26

One of the main draws of Windows on the World was, of course, its spectacular view. Instagram

7 of 26

A menu from Windows on the World. National Museum of American History

8 of 26

Kitchen staff at Windows on the World. Instagram

9 of 26

Guests at Windows on the World in 1976.Nestlé Library

10 of 26

By 2001, the restaurant was broken into three parts: Windows on the World; a bar called the Greatest Bar on Earth, pictured here in 1996; and a smaller, more intimate restaurant called Wild Blue.Nestlé Library

11 of 26

A corner of the restaurant. School of Visual Arts Archives

12 of 26

Cellar in the Sky, which was replaced by Wild Blue in 1999. Baum + Whiteman

13 of 26

A view from the restaurant looking down.Chris Morgan/Wikimedia Commons

14 of 26

Dishware from the Windows on the World restaurant. National Museum of American History

15 of 26

An interior shot of Windows on the World.Nestlé Library

16 of 26

An inside shot of the restaurant, which drew tourists and locals alike.Reddit

17 of 26

Cellar in the Sky in 1976.Nestlé Library

18 of 26

The interior of the restaurant bathed in red light.Pinterest

19 of 26

A Wild Blue napkin from the ruins of 9/11. Smithsonian

20 of 26

A dazzling view of the water from the restaurant, which was split between the 106th and 107th floors of the North Tower. Pinterest

21 of 26

A view from inside the restaurant at night.Reddit

22 of 26

A view over the water. Skyscraper City

23 of 26

A pamphlet from Windows on the World.Pinterest

24 of 26

People at Hors d’Oeuvrerie, which later became the Greatest Bar on Earth. Nestlé Library

25 of 26

The view from Windows on the World at night.Skyscraper City

25 Photos Of Windows On The World, From Its ‘Spectacular’ Beginnings To Its Tragic Destruction On 9/11

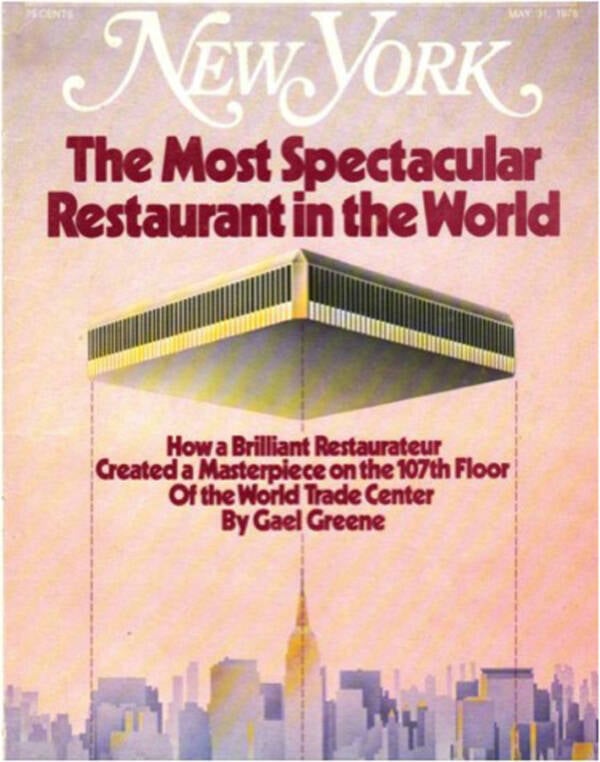

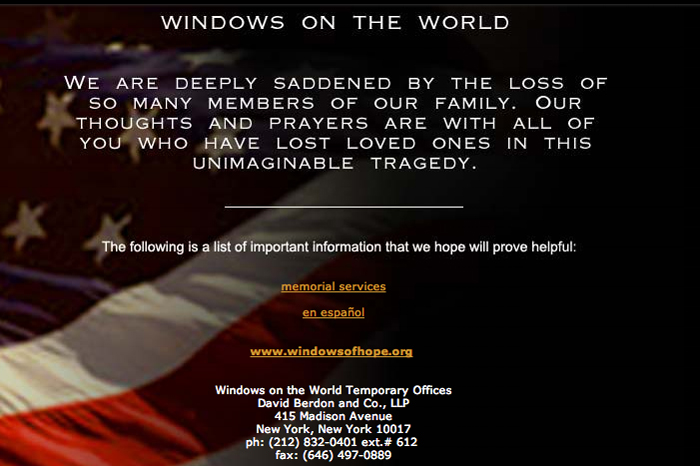

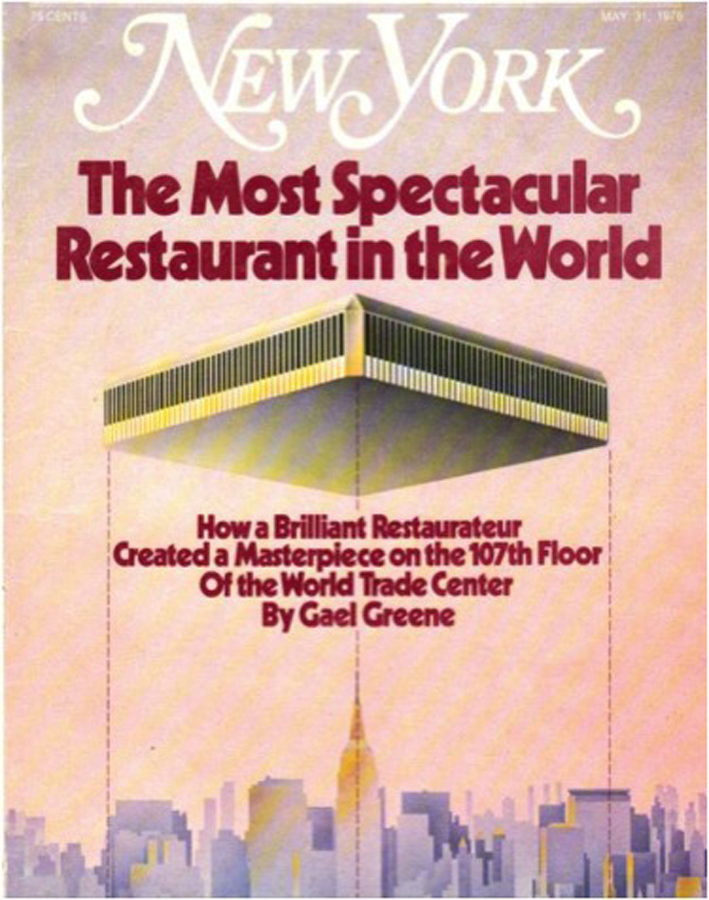

When Windows on the World opened in 1976 on the 106th and 107th floors of the World Trade Center’s North Tower, New York Magazine dubbed it: «The Most Spectacular Restaurant in the World.» Today, however, the restaurant is best known for its tragic end in the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

On September 11, 2001, all 170 people in the restaurant — including 72 Windows on the World employees — were killed after hijackers crashed American Airlines Flight 11 into the North Tower at 8:46 a.m, blocking off any means of escape. Less than two hours later, the tower collapsed.

But out of the tragedy and horror came great generosity. In the years since, surviving employees have come together to take care of their former co-workers’ families. This is the story of Windows on the World.

Building A Restaurant In The Sky

Three decades before the 9/11 attacks, restaurateur Joe Baum was hired by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey to develop restaurants at the World Trade Center, which opened in 1973. According to Eater NY, he developed 22 restaurants for the new complex, including Windows on the World, a sophisticated restaurant located on the North Tower’s 106th and 107th floors.

Windows on the World opened in April 1976 to great acclaim. Gael Greene, writing for New York Magazine, praised its optimistic opulence. It was a sure sign, she declared, that New York City was back after a difficult decade.

New York MagazineThe Windows on the World restaurant was dubbed a triumph by New York Magazine in 1976.

«Suddenly I knew — absolutely knew — New York would survive,» Greene raved of the new restaurant in the magazine’s cover story. «If money and power and ego and a passion for perfection could create this extraordinary pleasure… this instant landmark, Windows on the World… money and power and ego could rescue the city from its ashes. What a high. New York would prevail. Forget about Acapulco gold. This is Manhattan green.»

By 2001, the restaurant was broken up into three basic sections: Windows on the World itself, which offered diners jaw-dropping views of New York City; a bar called the Greatest Bar on Earth; and a smaller, more intimate restaurant beloved by locals, Wild Blue.

«We didn’t just want people to come up and spend a lot of money,» Glenn Vogt, a former general manager at the restaurant, told USA Today. «We were going to give you really good food, really good wine, really good cocktails.»

As a result, the restaurant attracted both tourists and New Yorkers. According to USA Today, it also drew celebrities like Warren Beatty and Wayne Gretzky.

Behind the scenes, restaurant workers became close friends. Hailing from more than two dozen countries, they often bonded over food they brought in to share with each other in the kitchen, which led one former employee to describe the band of Windows on the World workers as «the little UN.»

Windows on the World had its ups and downs — and was briefly closed following the 1993 World Trade Center bombing — but it remained a New York City institution. Then, in September 2001, the unthinkable happened.

Windows On The World And The 9/11 Attacks

For Windows on the World employees, September 11, 2001, started like any other day. By 8 a.m., the restaurant was already buzzing, as various business people and power brokers enjoyed breakfast, coffee, and the stunning views from the 106th and 107th floors of the World Trade Center.

The Guardian reports that Risk Waters Group was holding a conference that day on information technology, which drew dozens of people, including executives from companies like Merrill Lynch.

At 8:44 a.m., Michael Nestor and Richard Tierney, who worked for the Port Authority, and Liz Thompson, the executive director of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, finished their breakfasts and boarded an elevator.

«We rode down, and I guess we were joking around or talking,» Nestor told NPR 10 years later. «And it didn’t take long. You know, those elevators were fast. It didn’t take long. And then we got off, and the plane hit.»

ZUMA Press, Inc. / Alamy Stock PhotoSmoke billows from the World Trade Center shortly after hijackers flew American Airline 11 into the North Tower.

They didn’t know it at the time, but Nestor, Tierney, and Thompson were the last people to leave Windows on the World. At 8:46 a.m., the first hijacked plane, American Airlines Flight 11, struck the North Tower, tearing through floors 93 to 99 and cutting off any means of escape for the people above.

About 15 minutes later, around 9 a.m., an assistant manager for Windows on the World named Christine Olender called Port Authority for help. The Guardian reports that Olender had gathered all the restaurant’s employees and guests on the 106th floor, and she was looking for guidance as the three emergency stairwells filled with smoke.

«We are getting no direction up here,» she said. «We need direction as to where we need to direct our guests and our employees as soon as possible.»

«We’re doing our best. We’ve got the fire department, everybody, we’re trying to get up to you, dear,» a police officer told her, telling her to call back in two minutes. Olender called back four more times. But there was nothing she — or the first responders on the ground — could do.

«The fresh air is going down fast! I’m not exaggerating,» Olender said in her last call, asking if she and the others could break windows to get the smoke out. The officer told her to go ahead.

Meanwhile, Vogt, the general manager, arrived on the scene. At that point, he didn’t understand the gravity of the calamity unfolding above.

«I thought, ‘Oh, we’re going to have to be closed for months.’ I didn’t know the severity of what was going on,» he later told USA Today.

Then, someone fell or jumped from the tower above and landed close to him. A fireman told him to get away from the building, and Vogt obeyed.

And at 10:28 a.m., the North Tower collapsed. Everyone at Windows on the World restaurant, including 72 employees, perished.

The Ongoing Legacy Of Windows On The World

In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, employees of Windows on the World who hadn’t been at the restaurant struggled with how to respond to the tragedy. There was grief, of course, but also a determination to help.

Mirko Chianucci/Alamy Stock PhotoThe names of people who lost their lives at Windows on the World during the 9/11 attack, including Ehtesham U. Raja, 28, who was in the restaurant for a conference, are inscribed on the 9/11 Memorial in Manhattan.

As Eater NY reports, a Windows on the World hotline was set up a week after the attacks in order to find employees who were unaccounted for. The restaurant’s final chef, Michael Lomonaco, also set up a relief fund called Windows of Hope, which raised $30 million for families who’d lost loved ones. This fund was especially helpful for the undocumented workers at the restaurant, who were not eligible for other benefits.

«It really helped a lot of people survive,» Vogt told USA Today. «There were a lot of people who passed away who were the main breadwinners. Not just for their families in New York, but back in their home countries, too.»

Help also came from FEMA and even from Windows on the World customers. And many former employees found comfort in each other. As USA Today reported in 2021, several continue to attend 9/11 anniversary events to remember the co-workers that they lost.

Today, there’s a new restaurant at One World Trade Center, the building that replaced the World Trade Center towers. Called ONE Dine, it’s located on the 101st floor and offers stunning views, just like Windows on the World did.

But the Windows on the World experience — for both diners and employees — is lost forever.

After reading about Windows on the World, look through these heartbreaking stories of nine 9/11 victims. Or, see how Gander, Newfoundland, stepped up after the 9/11 attacks to host displaced airplane passengers.

Windows on the World was one of the greatest restaurants New York City has ever seen. Located on the 107th floor of the World Trade Center, it offered guests soaring views of not only Manhattan, but also Brooklyn and New Jersey. Although the food couldn’t always match the scenery, at its best, Windows provided guests with a sophisticated, forward-thinking dining experience unlike any other in New York City.

Windows on the World vanished 12 years ago. On that horrific day, 79 employees of the restaurant lost their lives. Here, now, is a remembrance of Windows on the World, with an afterword from the restaurant’s last chef and greatest champion, Michael Lomonaco:

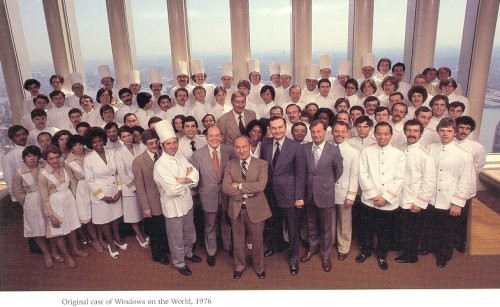

[GM Alan Lewis, chef Andrew Renee, restaurateur Joe Baum via Edible Manhattan]

Windows on the World was the brainchild of visionary restaurateur Joe Baum. With the Restaurant Associates group, Baum created a string of ’60s blockbusters including La Fonda Del Sol, The Forum of the Twelve Caesars, and The Four Seasons. In 1970, after parting ways with Restaurant Associates, Baum was hired by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey to help develop the restaurants at the World Trade Center.

[A ’70s menu for Windows via Typofile; A pamphlet for the world Trade Center Club via eBay]

Baum, along with partners Michael Whitman and Dennis Sweeney, created 22 restaurants for the World Trade Center, many of which were casual operations located in the basement concourse. But the most elaborate Baum creation was Windows on the World, which occupied the 106th and 107th floors of the North Tower. The restaurateur hired architect Warren Platner to design a grand, modern space.

[Windows on the World Ephemera from Milton Glaser.com]

Graphic designer Milton Glaser (of the I ? NY and Brooklyn Brewery logos) contributed the menu artwork, dishware patterns, and logo. Barbara Kafka picked the plateware and silverware. And James Beard and Jacques Pepin helped develop the menu.

The Port Authority then signed a master lease with Inhilco, a subsidiary of Hilton International, to run the World Trade Center restaurants. Baum and his team then moved to Inhilco to put their plans into action.

[Kevin Zraly talking to guests in 1976 via The Nestle Library]

Windows on the World opened on April 19, 1976, as a private club with 1,500 members who paid dues based on their relationship with and proximity to the World Trade Center — WTC tenants paid $360 a year, and those who lived outside the «port district» paid just $50. But anyone could visit Windows on the World in the early days if they paid $10 in dues, plus $3 per guest.

[The Hors d’Oeuvrerie via The Nestle Library]

In addition to the main dining room, where a table d’hote dinner was $13.50, Windows on the World had an Hors d’Oeuvrerie that served global small plates.

[Cellar in the Sky via Baum + Whiteman]

One offshoot, dubbed the Cellar in the Sky, offered an expansive wine list from young gun sommelier Kevin Zraly, plus a five-course menu of American and European fare.

Every view is brand-new? a miracle. In the Statue of Liberty Lounge, the harbor’s heroic blue sweep makes you feel like the ruler of some extraordinary universe. All the bridges of Brooklyn and Queens and Staten Island stretch across the restaurant’s promenade. Even New Jersey looks good from here. Down below are all of Manhattan and helicopters and clouds. Everything to hate and fear is invisible. Pollution is but a cloud. A fire raging below Washington Square is a dream, silent, almost unreal, though you can see the arc of water licking flame. Default is a silly nightmare. There is no doggy doo. Garbage is an illusion.

[Cellar in the Sky via Baum + Whiteman]

Windows on the World was an immediate success. New York Times critic Mimi Sheraton describes the dining experience:

Unquestionably the best thing about this place, other than the toy-town views of bridges and rivers, skylines and avenues is the menu. It represents an international crossroads of gastronomy, stylish and contemporary, and perfectly suited to this particular setting and this particular city.

The restaurant quickly became a favorite hangout of high-powered businessmen, politicians, and celebrities. By the end of its first year, Windows on the World had a waiting list that was fully booked for six months straight.

[The view facing west via The David Blahg]

In 2001, Joe Baum’s creative partner Michael Whiteman told the Times: «In a way, it was the symbol of the beginning of the turnaround of New York…We were successful because New York wanted us to be successful. It couldn’t stand another heartbreaking failure.»

[The original Windows on the World crew via Suzette Howes]

Joe Baum was only involved in the management of Windows on the World during its first three years in business, but the restaurant sailed along through the ’80s and early ’90s. During this period, the restaurant employed a number of chefs that would go on to find success on their own, including Kurt Gutenbrunner, Christian Delouvrier, Eberhard Müller, and Cyril Reynaud. The critics were not always kind to Windows on the World, but year after year, it remained one of the top-grossing restaurants in the country.

On February 26, 1993, a group of terrorists detonated a bomb inside a truck that was parked below the North Tower. The bombing killed six people, and injured over a thousand. The explosion damaged storing and receiving areas used by Windows on the World, and the restaurant was forced to shutter. Hilton International gave up its lease after the bombing, and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey asked 35 restaurant groups for proposals for the Windows on the World space.

[a New York article on the revamp from July 15, 1996]

On May 13, 1994, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey announced that the Joseph Baum & Michael Whiteman Company had won the contract. Almost two decades after opening the restaurant, Joe Baum was back in control of Windows on the World.

[Cellar in the Sky, 1996 via Baum + Whiteman]

Baum and his partners tapped Hugh Hardy to create a dining room that was more colorful and whimsical than the original. Unlike the old Windows, which served Continental fare with a sharp American influence, the new restaurant offered a globetrotting menu from chef Philippe Feret.

[The Greatest Bar on Earth via Skyscrapercity]

The Hors d’Oeuvrerie was replaced by The Greatest Bar on Earth, a splashy space that had three bars and a menu of fun international fare. Before the reopening in summer of 1996, Baum told the Times: «When Windows first opened it was a great restaurant for New Yorkers…When tourists came, they came mostly because New Yorkers were proud to bring them here. We want Windows to be a great restaurant for New Yorkers again.»

[Windows on the World in 1996 via the Container List]

Feret left Windows in May of 1997, and he was replaced by Michael Lomonaco, a chef that had earned raves at the ’21’ Club. A few months after he took control of the kitchen, Ruth Reichl bestowed two stars on Windows on the World. In 1999, Cellar in the Sky was replaced by Wild Blue, a cozy American restaurant, that was also overseen by Lomonaco. In his review, William Grimes wrote: «When night falls, Wild Blue feels like a plush space capsule hurtling through the cosmos.»

79 Windows of the World employees died on September 11, 2001. Michael Lomonaco was conducting an errand in the concourse of the World Trade Center when the first plane hit. The chef was evacuated from the building immediately, and witnessed the second plane hit the WTC from the street. Lomonaco then headed north and made it up to his home on the Upper East Side, where he immediately started figuring out who was working that day.

2001: Lomonaco and His Team Search for Employees:

By the following week, a Windows on the World hotline was set up at the restaurant’s sister establishment, Beacon, and Lomonaco and his head of human resources, Elizabeth Ortiz, began working to find the 50 employees that were unaccounted for. Lomonaco soon helped set up an relief fund called Windows of Hope, which raised over $22 million for the families of Windows workers.

[A screengrab of the Windows on the World website from 2002]

Windows on the World co-owner David Emil opened a Theater District restaurant in 2002 called Noche, which was staffed by several Windows employees, including Lomonaco — it closed in 2004. Some of the Windows employees opened a Noho restaurant in 2006 called Colors — it’s still open, but only for parties and private events. For the past seven years, Lomonaco has been the co-owner and executive chef of Porter House in the Time Warner Center, and he recently opened Center Bar, a casual spinoff on the same floor as Porter House.

The Port Authority has ruled out the possibility of putting a fine dining restaurant like Windows on the World at the top of the new World Trade Center, which is slated to open in 2014.

Earlier this week, Eater interviewed Michael Lomonaco about his experiences on the 106th and 107th floors of the North Tower. Here’s an extended look back:

[Michael Lomonaco via Porter House]

What did it mean to you to get that job at Windows on the World?

Michael Lomonaco: Well I’d never been there before. I’d never worked there. I’m a native New Yorker, and I remember very clearly when Windows on the World opened. I have very clear memories of that, even the review that they did in New York magazine. But one of the key memories I had always had was Cellar in the Sky, because the original Cellar in the Sky was a prix fixe restaurant — that was pretty new to New York. And it was advertised weekly in the dining section of the Times — they advertised the menu as changed every week, or every other week. That ad always stuck in my mind, how they promoted Cellar in the Sky. It just sounded so incredible.

So fast-forward to the ’80s. I got out of culinary school in 1984, and Windows on the World had become this giant place that was historic, and I’d never been there. I’d never gone to the Cellar. I’d never gone to Windows. In fact, the first time that I had ever gone up there was at the reopening in 1996 when they hosted an industry night, and I went up there for an evening.

I knew Joe Baum pretty well in my days at ’21.’ Joe was a regular and I was introduced to him, and he was a very passionate, warm, hospitable guy. He really was magnetic, in many ways. I had some sense of what was going on there. In the early ’90s, when I met Joe, it was no longer associated with us. But then in 1996, when they did the big reopening, I was still at ’21’ and had started doing television at the Food Network, so I was in a transitional period.

[Windows on the World in 1976 via the Container List]

I’d left ’21’ in the last quarter of ’96 to film Michael’s Place at the Food Network. Then in ’97, I was introduced to David Emil and Joe Baum. My relationship began with them at that time, and I really had some long talks with David Emil and with Joe Baum about joining them and becoming part of their team. I was the «chef-director.» This was Joe Baum’s title for me. Direct all of the chefs. We had Windows on the World, there was Cellar in the Sky, and there was the Greatest Bar on Earth, and it was all private dining on the 106th floor, so there was quite a team of people. So that, for me, in ’97 when I joined them, was really very exciting. It was very exciting because it was such a historic place, it was such a beloved place, and it was really at the pinnacle of its own opportunity to reinvent itself again. And that’s the opportunity I took. That was the great step forward for me — it was the chance to reinvent Windows on the World. And, in fact, we shuttered Cellar in the Sky in ’98, and reopened the space as Wild Blue in ’99. It became a very kind of beloved space. It’s small, 55 seats.

Were you proud of your work up there?

Absolutely. First of all, I had a great team. You know, there was a great group of people. There were 450, 500 people that worked up at Windows on the World at one time. And I had a great team with me. My chef de cuisine is still with me today — Michael Ammirati. He came with me. Michael, who would be here now at Porter House, he was a key component, because it was really just the two of us with a culinary team that was 35 people, trying to turn it to a new direction. I think we were able to fulfill, to some degree, an original vision that Joe Baum had for Windows on the World.

You know, I thought that Joe’s vision was that Windows on the World should be a beacon of American cooking, on American products, on American foods. And, also, shine a spotlight on local ingredients. So we started working with the local suppliers at the greenmarket in 1997, and a bunch of the produce that we bought came from the greenmarket at the World Trade Center. This is something that fit into my vision of what we could do, and also Joe’s vision. And I’ll tell you, in 1998, we were talking about planting an herb garden and a vegetable garden on the roof of the World Trade Center. Sustainable cuisine, sustainable cooking was something that Joe started talking about back in ’97, probably before, and it was really a big topic when we met and talked about ideas.

On a Saturday night, we could do 700 or 800 covers, but all of that was from-scratch cooking. Everything was cooked à la minute. And we did that with a great team of cooks in the kitchen, and our culinary chef staff. We just did it through organization, and sheer will that we would cook everything à la minute.

[The Greatest Bar in the World via The Container List]

Cellar in the Sky reopened in 1996. It was expensive. It was a prix fixe, $125-a-head dinner and it was kind of staid. It wasn’t getting the traffic, because there were so many more things happening in the culinary world. And so what we did in 1998 was we closed Cellar in the Sky with the idea of turning it into an American chophouse, and that’s what Wild Blue was. 55 seats and a very aggressive wine-by-the-glass program. We served, I think, really delicious American chophouse fair. Prime beef, game birds, duck, squab, and it was all family-style. It was really kind of a fun place that became more of a locals restaurant. The tourist crowd, the visitor crowd would go to Windows, which had dramatic views. Wild Blue also had dramatic views, but on the south side of the building, facing the Statue of Liberty. We had a very kind of local crowd. I’m very proud of the work we did there, and I’m very proud of the people I met and had the chance to work with.

Do you have a favorite memory from working on the 106th and 107th floors?

A real favorite memory was the annual holiday party that David Emil and Joe Baum hosted, and that was held in January at Windows. That’s where everyone who worked there was invited to bring members of the family and come to one of the private dining rooms, which could seat 500 people, if not more. That holiday party was a fantastic memory. Everyone came with family. Everyone who worked there got dressed up. We had people from the around the world at Windows, and it was an incredibly global staff. The team would refer to themselves as the U.N. of restaurants. They had such diversity in the workforce, the staff that worked there. And there were more than 60 languages that were spoken among the staff. You could alway find someone who could act as a translator for any guest who needed help. This diversity was exciting.

But on that day when we had our holiday party, it was really wonderful to see all of the people we worked with. Much of them came in the finest clothes that they wore in their original, native homelands. It was like being at a party at the U.N. with beautiful clothing from around the world — from Africa, from Asia, from India, and Latin America. Just a beautiful thing where people were proud of where they worked. Everyone had a good time.

You devoted a lot of your life after 9/11 to working with the families of the employees that died, and the employees that were displaced. Did you think that, after a year or two, there would be another Windows on the World? Did you think that you would be able to work together again?

There was a lot of pain and loss felt by everyone and it was different for each individual. We lost 79 of our co-workers. But I think that there was some sense of time to recover. It’s a very difficult question to answer, because I think it’s personal to each individual. You’ve got to see it from this point of view: There were people lost at Windows who had family members who worked there who weren’t lost. We had a family that worked in our kitchen, there were four brothers, the Gomez brothers, two were lost and two were not. There was a lot of recovery. I think the pain of recovery leads to, «We want to get back to where we were…» I think there was a sense of people trying to stay together.

There was also a lot of confusion in the aftermath thinking, «What is the right thing to do?» It was something I wish could’ve happened overnight. For me, I wish that this never would have happened, of course, but there were different configurations of people trying to stay together. We had Noche in Times Square with nearly 50 of our co-workers. That’s a small number compared to Windows Hospitality Group, which was one of the largest in the world in sheer volume and size. So, 50 people working together was a comforting thing for some of us to be able to continue to work together. Others went down to the restaurant on Lafayette Street — there were groups that felt they wanted to keep some of their friends and co-workers together. The loss of something so immense was a shock in itself.

12 years later, what is your relationship with the families of the employees you worked with?

As in any situation, you know some people better than others. You have to cultivate some relationships…you have to imagine 450 people working together. I’m just trying to stress that that’s a lot of people. There are some people that I knew quite well, and I am in touch with some of the family members of those who lost. I do keep in touch with some. There are others who, we work together, and we have some contact during the year. I have a few of my co-workers who were with me at Windows, who now work with me at Porter House.

If this is something that can answer your question…The Windows of Hope Relief Fund, we raised 22 million dollars with the help of Tom Valenti, David Emil, the board members, and the group of people who were with me. That fund is still paying for education for 150 children who are eligible to receive education grants from that fund, every year. A great portion of the original funds went to emergency aid to those families who lost someone on that day. There was emergency aid and health insurance that the funds paid for, for the first five years. The original mission was emergency aid, health insurance, and educational opportunities for the children of the victims, of the food service worker victims. All of the food service workers who were identified, of which there were 102, Windows being the greatest. Just so you understand, when we established that fund, we worked with the Community Service Society of New York to administer the families’ needs, and I think the most important thing that we could give them was a sense of dignity and a respect for their loss, and maintain the respect for their privacy. So, in a way, it kind of cut off having personal relationships with people that were included in this fund.

Do you think New York will ever have a restaurant like Windows on the World again?

Oh yeah, that’s the spirit of New York and our nation and humanity. To build, to create, to entertain our guests — that’s what we do. Windows was incredible, and because it had really been reborn in its incarnation in 1996, that version of Windows wasn’t meant to be exclusive. It was a very inclusive and democratic restaurant. The prices were not exorbitantly high, and people could come in and go to the bar and have a Coke and having this incredible experience of seeing the city. It was very open, hospitable, and friendly.

I think in that spirit, New York will have something like this. I’m very happy to talk to you, because what I want you to understand is….That day, aside from the fact that I survived it…the greatest thing I could offer is doing what I was doing before, so that the memory of my friends and colleagues lost that day have honor. I feel privileged to wake up every day and do what I do. What I do, in part, is a tribute to my friends and colleagues.

[A view from Windows on the World]

Further Reading:

· From Windows on the World to Windows of Hope [Thirteen]

· Lomonco Escaped 9/11 but Dedicates Cooking to Friends he Lost [NYDN]

· Windows That Rose So Close To the Sun [NYT]

· Drinking at 1,300 Ft: A 9/11 Story About Wine and Wisdom [Esquire]

· Ruth Reichl Remembers Windows on the World [NYM]

· Windows on the World: The Wine Community’s True North [Wine News]

· The Legacy of Joe Baum [Edible Manhattan]

· Windows on the World Opening Report (Subscription required) [NYT]

· Gael Greene’s First Visit [Insatiable Critic]

· Mimi Sheraton’s First Visit (Subscription required) [NYT]

· Gael Greene’s Review from November of 1976 [Google Books]

· Mimi Sheraton’s Second Visit (Subscription Required) [NYT]

· Bryan Miller’s One Star Review from 1987 [NYT]

· Bryan Miller’s Review from 1990 [NYT]

· Renovation Report from 1996: Can the Food Ever Match the View? [NYT]

· Ruth Reichl’s Two Star Review from 1997 [NYT]

World Trade Center, New York, NY

Well since the last post on the dining options at the World Trade Center, I’ve kept running across additional leads that I wished I’d known about to include in that listing. For example, the Big Kitchen food mall in the WTC’s concourse was organized by one of the early popularizers of French food in America, Jacques Pépin (who is a personal favorite TV chef). It was apparently the first such mall in America (which probably means anywhere).

All the way on the other end of the tower, the ultra-luxe Windows On The World restaurant — which, along with every other food-purveyor in the complex, was headed up by restaurateur Joe Baum — hired James Beard (Baum’s old pal, who likely had many a free drink at Baum’s Four Seasons bar) to be the food consultant.

Accounts of the project usually detail how Beard and Baum and Glaser and several other top-level consultants collaborated on Windows On The World when the WTC was implementing its food services in 1976. But I noticed in the archive we have examples from this project (grouped together for reasons of provenance) that come from two distinct phases: the founding of the restaurant in 1976 and a re-design in the mid-90s (though there are indications Glaser worked on everything in the room, bottom to top).

The story of the restaurant, it turns out, is amazingly consonant with that of the building. The first terrorist attack on the WTC — the bombing on 26 February 1993, which fell short of the perpetrators’ intentions, but still damaged the structure of the building — led to the iconic Windows restaurant laying dormant for three years. It had, up to that point, changed hands a few times: Baum’s group handed it over to Hilton, during which time the quality apparently suffered; Hilton in turn sloughed it off to the UK hotel chain Ladbroke, in whose stewardship it declined even more.

WOTW restaurant, 1976. Photograph from the Nestlé library. Not a scene that happens much anymore.

After the 1993 bombing, the Port Authority undertook repairs on the 106th and 107th floors, which had suffered severe structural problems, and at the same time began soliciting bids for the new operators of Windows On The World. The finalists for the bid were prominent New York restaurant impresarios: Allan Wollensky, of Smith and Wollensky; Warner LeRoy, who ran Tavern on the Green; David Bouley; and once again Joe Baum, who was, at the time, operating the Rainbow Room (also a Milton Glaser production). Baum prevailed, and brought back his whole original ’76 team. The budget was $25m. Their redesign reconfigured the space so that the main restaurant room straddled both floors, and gave every seat a plum view. But one kink remained: the food. As I wrote before,

The fare seems suspiciously eclectic to today’s eyes: sushi, “Indonesian pork saté,” Leverpostej (Scandanavian pork liver paté), guacamole and “James Beard’s chicken hash” on the same menu.

And that was the 1976 menu! In 1996 they were still focusing on “world cuisine” (I guess the rather literally-minded justification being that the “Windows” were “On” said “World”). After a bunch of bad reviews they decided bring the buffet, a la carte service, and bar menu — previously entirely separate services — under the control of one chef. New hire Michael Lomonaco, hot off the 21 Club, whipped the menu into shape. He describes his approach in a 2010 interview,

When I got there, “global cuisine” was the phrase they used: the menu had a dish from Holland, Hong Kong, South Africa… It didn’t have a personality. I thought what we had to do was get back to Joe Baum’s original vision, and to spotlight American cooking, ingredients that were grown and raised and caught here.

Napkin from the Wild Blue restaurant, rescued from the WTC ruins December 2001. From the Smithsonian.

So there it is: Jacques Pépin’s Big Kitchen in 1976 put the emphasis on a produce-centric, fresh and simple cuisine. In 1996, upstairs, Lomonaco revised the same principle into line with Alice Waters’ local food philosophy. This was particularly apparent in the somewhat more casual steakhouse, Wild Blue, which replaced the 1976 Windows On The World special room Cellar In The Sky. I’m pretty sure the Wild Blue name was lifted from one of the Cellar’s adjacent banquet rooms — the Nestlé library has photos of a “Rose Room” along with “Wild Blue,” both dated 1976.

Plate designed for Windows On The World restaurant reopening, ca. 1996.

On his new (rather snazzy) website, Milton groups both ’76 and ’96 designs for the WOTW together which was a little confusing to me at first, since they’re two decades apart and stylistically very different. Though the treatment of the menu, it is true, uses the same sun-motif, the scale has changed.

Above: Milton Glaser’s design for the original menu, 1976. Below: the 1996 redesign.

The interior was also totally different. Apart from reconfiguring the entire restaurant seating system around the view, the style departs from the original Deco meteorological symbolism in favor of sci-fi-ish geometrical treatments of space (like the irregular vertices of the ceiling). The lounge room of the original restaurant was lined with brass globes that echoed the sun motif, and featured light, natural materials (like the chairs below by Warren Platner, who was the interior architect on the whole project). The ’90s version (pictured at the top of the post) kept some golden orbs (at the buffet) but replaced the Platner furniture and muted textural variation of the wall textiles with pristine white and chrome.

Interior of the Windows On The World restaurant, ca. 1976. Designed by Warren Platner and Milton Glaser. Photograph from the Nestlé library.

The Cellar In The Sky, the more intimate dining room at the 1976 WOTW, was not revived. An early advertisement from the archive touts it as “the jewel of the Windows of the World … light, filtered through racks of great wines, dapples each table like moonlight.” The tables are certainly dappled, but I’m not entirely convinced this is the work of the wine-bottles rather than clever lighting design.

Cellar In The Sky, ca. 1976. Photograph from the Nestlé library.

This charmingly eccentric bit of Mediterrania was, perhaps, a reflection of the New York of its day, while the 1996 addition of the so-named Greatest Bar In The World was a reflection of its contemporary New York, as might be pieced together from this reminiscence from the Chicago Bar Project site:

Greatest Bar on Earth patrons consisted of an interesting mix of tourists from all over the world, Wall Street-types, lounge lizards, and pick-up chicks looking for a sugar-daddy. Time Out New York noted that, “Mixed in among the yuppies and cocktail nation twits here is a sizable delegation of actual hipsters–DJs, fashion and design fold, and other party people.” Whether tourists or the young and affluent, all came to enjoy a selection of booze that included 16 different kinds of vodka, 1,500 wines (!), and a variety of specialty cocktails like the WOW Martini, Mandarin Crush, and Ellis Island Iced Tea. Mixed drinks were not for the faint of heart, as prices ranged from $8 to $16 (for a Cosmopolitan) … Bands typically came on after 9:00 p.m., and consisted of classic funk Mondays; R&B Tuesdays; “Mondo 107 Lounge” Wednesdays; “Mambo, Baby” Latin Thursdays; “Glitter” Disco Fridays; Saturday night “Swing!” …

View of “The Greatest Bar in the World” in the World Trade Center, 1996. Photograph from the Nestlé library.

See also: the earlier part of this story.