В Windows 10 разработчики решили убрать с панели переходов опцию «Недавние места», заменив ее панелью быстрого доступа, позволяющей получать сведения о наиболее часто используемых папках и файлах, которые открывались последними. Надо сказать, далеко не все пользователи нашли это нововведение удобным, ведь раньше получить доступ к истории можно было одним кликом мыши, а главное имелась возможность просматривать историю открытых папок.

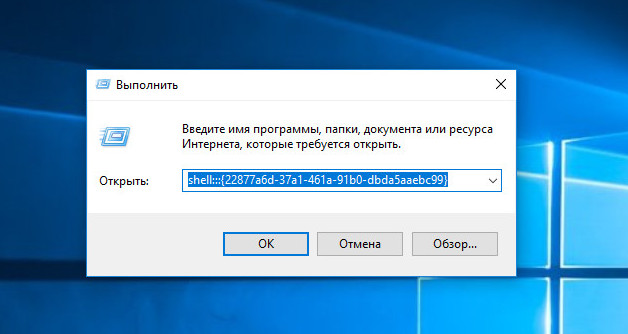

Вернуть пункт «Недавние места» в Windows 10 не составляет особого труда, достаточно выполнить в окошке Run команду:

shell:::{22877a6d-37a1-461a-91b0-dbda5aaebc99}

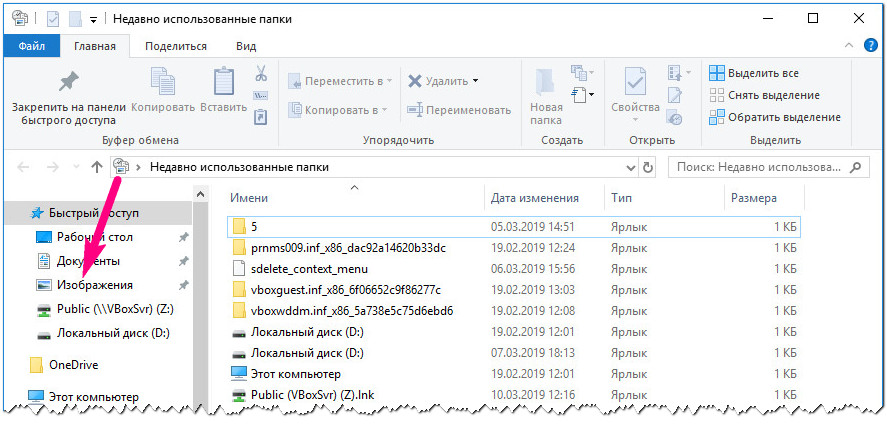

А затем перетаскиванием значка в адресной строке закрепить опцию в панели переходов.

В общем, восстановить доступ к функции не проблема, но если присмотреться к ней повнимательней, можно обнаружить, что предоставляемые ею возможности довольно-таки ограничены.

Чтобы просмотреть путь к объекту, приходится лезть в свойства ярлыка, из дополнительных сведений доступна разве что дата изменения, чего никак нельзя сказать о слотах и ключах реестра. Если вы являетесь пытливым пользователем и хотите знать как можно больше, вам нужны более эффективные инструменты.

ShellBagsView

Хотите получать больше сведений об истории открытых папок?

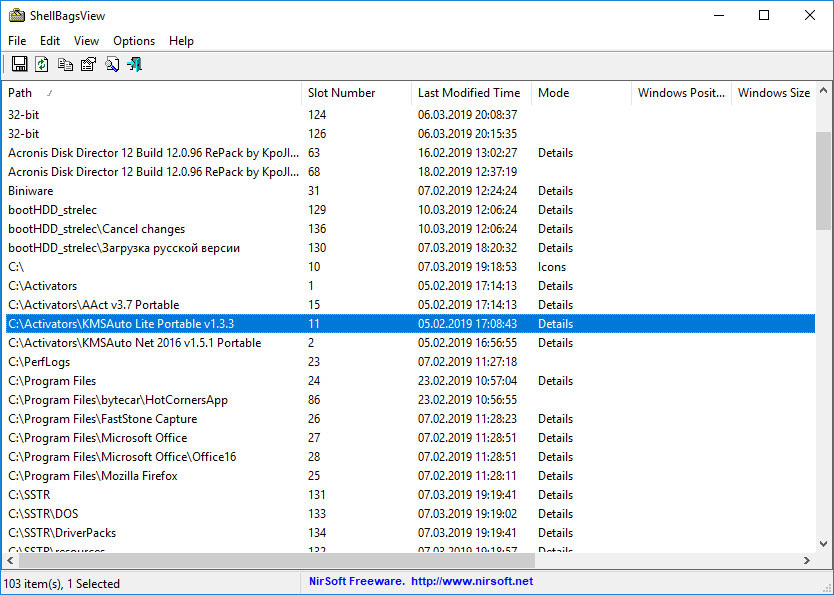

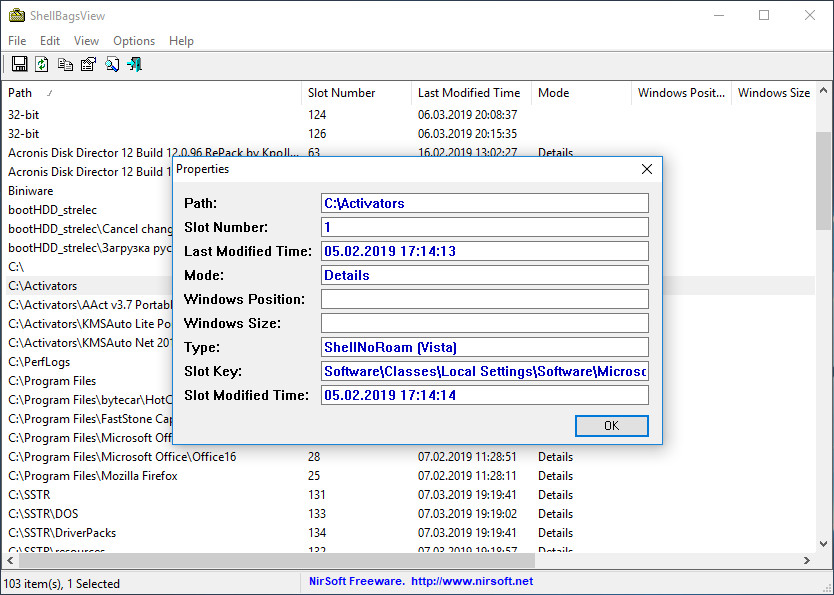

Используйте ShellBagsView — небольшую портативную утилиту от известного разработчика NirSoft.

Будучи запущенным, инструмент предоставит вам такие сведения как полный путь к объекту, номер слота, хранящий данные ключ реестра, дату последней модификации и, если возможно, зафиксированные размер и положение окна Проводника.

Утилитой поддерживается сортировка данных по нескольким критериям, сохранение сведений в файл отчета и просмотр свойств каждой записи.

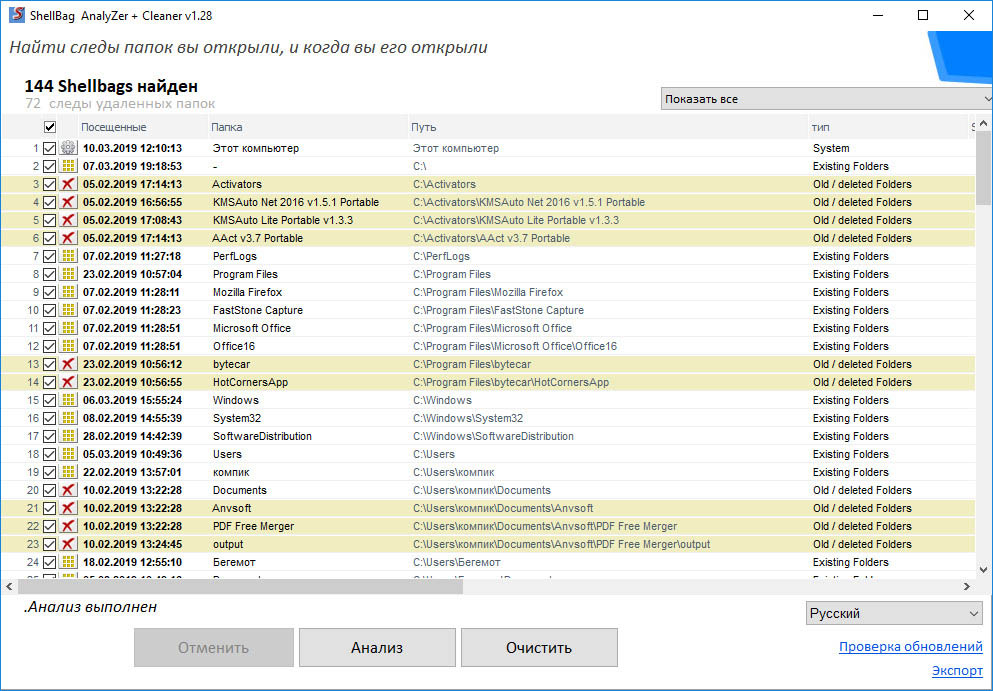

Shellbag Analyzer & Cleaner

Круче ShellBagsView программа Shellbag Analyzer & Cleaner, разработанная компанией Goversoft. Это приложение более гибкое и функциональное, чем просмотрщик от NirSoft, оно позволяет не только просматривать, но и удалять историю папок.

Помимо полного пути и названия каталогов, Shellbag Analyzer выводит точную дату посещения, тип, статус папки (существует или удалена), номер слота, ключ реестра, даты создания, модификации и доступа. Также программа должна показывать последнюю позицию окна и его размер, но почему-то эти столбцы не содержат никаких данных. Дополнительно приложением поддерживается сортировка сведений по разным критериям.

Скачать ShellBagsView можно со странички www.nirsoft.net/utils/shell_bags_view.html, для загрузки Shellbag Analyzer переходим по адресу privazer.com/en/download-shellbag-analyzer-shellbag-cleaner.php.

Обе утилиты бесплатны, обе не нуждаются в установке, обе подходят для начинающих пользователей. Что же касается считающих себя профи, таковым стоит обратить внимание на куда более продвинутые инструменты, к примеру, ShellBags Explorer, предназначенной для сбора данных об активности пользователя путем анализа записей системного реестра.

Загрузка…

In this article, we will be focusing on shellbags and its forensic analysis using shellbag explorer. Shellbags are created to enhance the users’ experience by remembering user preferences while exploring folders, the information stored in shellbags is useful for forensic investigation.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Location of shellbags

- Forensic analysis using Shellbags Explorer

- Active Registry Analysis

- Offline Registry Analysis

Introduction

Windows Shell Bags were introduced into Microsoft’s Windows 7 operating system and are yet present on all later Windows platform. Shellbags are registry keys that are used to improve user experience and recall user’s preferences whenever needed. The creation of shellbags relies upon the exercises performed by the user.

As a digital forensic investigator, with the help of shellbags, you can prove whether a specific folder was accessed by a particular user or not. You can even check whether the specific folder was created or was available or not. You can also find out whether external directories have been accessed on external devices or not.

For the most part, Shell Bags are intended to hold data about the user’s activities while exploring Windows. This implies that if the user changes icon sizes from large icons to the grid, the settings get updated in Shell Bag instantly. At the point when you open, close, or change the review choice of any folder on your system, either from Windows Explorer or from the Desktop, even by right-clicking or renaming the organizer, a Shellbag record is made or refreshed.

Location of shellbags

Windows XP

The shellbags for Windows XP are stored in NTUSER.DAT

- Network folders references:\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Shell

- Local folder references: \Software\Microsoft\Windows\ShellNoRoam

- Removable device folders: \Software\Microsoft\Windows\StreamMRU

Windows 7 to Windows 10

Shellbags are a set of subkeys in the UsrClass.dat registry hive of Windows 10 systems. The shell bags are stored in both NTUSER.DAT and USRCLASS.DAT.

- NTUSER.DAT: HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Shell

- USRCLASS.DAT: HKCU\Software\Classes\Local Settings\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Shell

The majority of the data is found in the USRCLASS.DAT hive-like local, removable, and network folders’ data. You can manually check shellbags entry in the registry editor like so. In the following screenshot, a shellbag entry for a folder named jeenali is shown.

The Shellbag data contains two main registry keys, BagMRU and Bags

- BagMRU: This stores folder names and folder path similar to the tree structure. The root directory is represented by the first bagMRU key i.e. 0. BagMRU contains numbered values that compare to say sub key’s nested subkeys. All of these subkeys contain numbered values aside from the last child in each branch.

- Bag: These stores view preference such as the size of the window, location, and view mode.

We will be analyzing the shellbags using the shellbag explorer.

- ShellBags explorer(SBECmd)

- Shellbags explorer (GUI version)

Shellbags explorer is a tool by Eric Zimmerman to analyze shellbags. The shellbags explorer is available in both versions cmd and GUI. You can download the tool from here.

Forensic Analysis of Shellbag

Analysis using SBECmd

Here we are using the SBECmd.exe (Cmd version of the shellbag explorer tool) by Eric Zimmerman. This cmd tool is great for command prompt lovers who prefer using commands over GUI.

To get a clear idea about how shell bags work and store data and how you can analyze it I have created a new folder named “raaj” which consists of a text document. Further, we will be renaming it to geet and then to jeenali. Let’s analyze the shellbags entries for this.

Run the executable file and browse to the directory where the executable is present. To extract the shellbags data into a .csv file use the following command:

SBECmd.exe –l --csv ./

As a result of the above command, a .csv file will be created in the directory.

Lets’ open the .csv file and analyze it.

As I mentioned earlier, we have renamed the folder named “raaj” to “geet” and further to “jeenali” as highlighted in the screenshot the MFT entry number is the same for all three folders which depict that the folder was renamed.

- Shellbags explorer (GUI version)

Active Registry Analysis

Using the shellbags explorer we can also analyze the active registry. Select load an active registry which will load the registry in use by the active user.

The shellbags are successfully parsed from the active registry.

The shellbags parse contains the shellbags entries created based on users’ activities. As depicted earlier the folder renamed will have a similar MFT entry number. Here, I have created a folder named “raaj” and we will be further renaming it to “geet”.

Whenever a folder is renamed an entry is stored in shellbag, the MFT entry number of both the folder will be the same.

Now, once again rename the folder to jeenali. The MFT entry will be similar to the previous one.

Offline registry analysis

For offline analysis, we first have to extract the shellbags file which is USRCLASS.DAT. Let’s extract the shellbag file using FTK imager. Download FTK imager from here.

Lets’ add in the evidence, go to the add evidence item.

Select the source for adding evidence as here I have selected the logical drive as usrclass.dat is present in the C drive.

Next, select the desired user drive. Click Finish.

Expand the window to the location of the usrclass.dat. Select the user you want to investigate go to the following path to extract the UsrClass.dat.

root > users > administrator >Appdata>Local>Microsoft>windows

We will be analyzing the usrclass.dat extracted from the above step using shell bag explorer by Eric Zimmerman.

As we have exported the registry hives we will choose “load offline hive”

After successful parsing of the extracted shellbags file, you will be able to see the entries for folders browsed, created, deleted, etc. Here is the entry of the folders renamed earlier, the MFT entry number is the same for the three folders.

Now here, I have deleted the folder named “jeenali”. Now lets’ check the shellbags data whether the deleted folder still exists or not.

Yes, the shellbags store the entry even though the folder was deleted later.

Shellbags stores the entries of the directories accessed by the user, user preferences such as window size, icon size. Shellbags explorer parses the shellbags entries shows the absolute path of the directory accessed, creation time, file system, child bags. The tool classifies the folders accessed according to the location of the folder. Shellbags are created for compressed files (ZIP files), command prompt, search window, renaming, moving, and deleting a folder.

Author: Vishva Vaghela is a Digital Forensics enthusiast and enjoys technical content writing. You can reach her on Here

Windows Shellbags in Digital Forensics#

Every time you use your Windows computer, you are navigating through many files and folders. When you open a folder for viewing, you may also modify its viewing preferences. Windows stores information about it. Think of it as a logging system for folder access. These logs are stored in Shellbags. This blog post will introduce you to Windows Shellbags and highlight their significance for digital forensics.

Why does Windows use Shellbags?#

Windows uses shellbags to store information about user preferences. When a folder is accessed, you may modify its display settings – say from ‘Large icons’ to ‘Small icons’. Information about this settings change is stored in shellbags. When you close that folder and re-open it, its contents would be displayed as ‘Small icons’; as indicated by user preferences in shellbags.

Shellbags also retain information about folders that had previously existed on a system and were accessed. When removable media like a USB drive or an external hard disk are connected to your computer, you would open a folder to view the contents of the external media. This activity qualifies as folder access, which is logged by shellbags.

If your computer had connected to a network share, accessing that network share folder causes an entry to be made within the shellbags.

Where are the shellbags stored?#

Shellbags data is stored across two user registry hives on your computer NTUSER.DAT and UsrClass.dat. Shellbag information from these two hives can be accessed within the registry hive HKEYCURRENT_USER at _HKCU\Software\Classes.

There are various commercial and free forensic tools available that can acquire the shellbags from a target computer and process it.

A quick demo#

The following two folder operations were performed on a computer, across few days.

-

The computer had two storage drives C: and E: attached to it and one disc Drive D:, represented in the following screenshot. A CD was inserted into the disc drive and its contents were viewed. Some USB drives were also inserted, their contents were mounted in H: and F: and viewed.

-

Within Pictures folder, a new folder called Vault was created, some pictures were copied into it. Then it was marked as a hidden folder.

Let us see if we can find evidence of these two folder operations within Shellbags. Tools like ShellBags Explorer, Windows Shellbag Parser, etc. can be used to view the contents of shellbags.

Shellbags can be viewed directly on a live machine or the registry hive can be acquired for processing on another computer. In this demo, the shellbags were viewed directly on the live system using ShellBags Explorer.

Within the My Computer drop down, you can see entries for all the drives that had been mounted on the system. You can also track recent changes to Downloads, Documents and Pictures folders here.

The shellbag entries relevant to D: drive show that the contents of a CD had been viewed last on 28th January 2022 at 13:19 hours.

The shellbag entries relevant to F: shows the contents of the USB drive that had been mounted on this computer. Folder entertainment had been accessed on 23rd April 2022 at 07:42 hours.

The shellbag entries relevant to Pictures folder shows that a directory called vault had been used last on 17th May 2022 at 00:44 hours. This was the folder that was created and marked as hidden.

Currently, within Pictures folder, it appears that vault does not exist.

When folder viewing options are modified to view hidden files,

the hidden vault folder can be seen.

Although there is no information within shellbags that vault was hidden, having a last interacted entry for vault indicates that the folder exists and is hidden or had existed and is now deleted.

In addition to recording changes to folders, shellbags also record information about zip files that had existed on the computer.

What is the significance of shellbags for digital forensics?#

When a Windows computer has been compromised, investigators attempt to process stored logs for any trace of malicious activity. Shellbags can be another useful source to identify:

-

folders that has been accessed recently

-

external media (hard disks, USB disks, CD) that had been used and accessed

-

zip files that had been accessed

Project Idea#

Here is a project idea for you to experiment with shellbags:

-

Create a folder called secret within your Documents folder and place some files in it

-

Delete the folder secret

-

Use tools to parse the shellbags on your computer and see if you can identify entries relevant to the deletion of folder secret

Some forensic tools display timestamps relevant to GMT. You may need to perform time correction according to the timezone your device is operating in.

A final word on shellbags#

This blog post intended to provide a quick overview about the forensic importance of shellbags. As a next step, you can research about the various keys and sub-keys within the registry that store information about shellbags. One to start with can be: ‘What is the significance of the key BagMRU?’

What are Windows ShellBags?

Windows ShellBags are one of the well-known and valuable sources of information regarding computer system’s user behavior. Although their primary purpose is to improve user experience and “remember” preferences while browsing folders, information stored in ShellBags can be critical during forensic investigation.

Where can I find ShellBags?

Shellbags are a set of subkeys in the UsrClass. dat registry hive of Windows 10 systems. The shell bags are stored in both NTUSER. DAT and USRCLASS.

What are ShellBags in forensics?

In a nutshell, shellbags help track views, sizes and positions of a folder window when viewed through Windows Explorer; this includes network folders and removable devices.

What are ShellBag artifacts?

ShellBags are a popular artifact in Windows forensics often used to identify the existence of directories on local, network, and removable storage devices. ShellBags are stored as a highly nested and hierarchal set of subkeys in the UsrClass.

What is Shimcache?

Shimcache, also known as AppCompatCache, is a component of the Application Compatibility Database, which was created by Microsoft and used by the Windows operating system to identify application compatibility issues. This helps developers troubleshoot legacy functions and contains data related to Windows features.

What are Windows prefetch files?

What are Prefetch Files? Windows creates a prefetch file when an application is run from a particular location for the very first time. This is used to help speed up the loading of applications. For investigators, these files contain some valuable data on a user’s application history on a computer.

What is Reg Ripper?

RegRipper is an open source tool, written in Perl, for extracting/parsing information (keys, values, data) from the Registry and presenting it for analysis. The RegRipper GUI allows the analyst to select a hive to parse, an output file for the results, and a profile (list of plugins) to run against the hive.

What is MRUListEx?

MRUListEx is a registry value that lists the order in which other values have most recently been accessed—essentially, the order in which terms were searched in Explorer.

What is the difference between Amcache and Shimcache?

Shimcache is the older implementation. Starting with Windows 8 and Server 2012, it was replaced by Amcache. The format is very different, since Amcache has lots more info it can provide, but the intent is the same.

What is Windows Amcache?

The Amcache. hve is a registry hive file that is created by Microsoft® Windows® to store the information related to execution of programs. hve file when a user performs certain actions such as running host-based applications, installation of new applications, or running portable applications from external devices.

What is Windows prefetch folder used for?

These are the temporary files stored in the System folder name as a prefetch. Prefetch is a memory management feature. The log about the frequently running application on your machine is stored in the prefetch folder. The log is encrypted in Hash Format so that no one can easily decrypt the data of the application.

How do I clear temp files in Windows?

Click any image for a full-size version.

- Press the Windows Button + R to open the “Run” dialog box.

- Enter this text: %temp%

- Click “OK.” This will open your temp folder.

- Press Ctrl + A to select all.

- Press “Delete” on your keyboard and click “Yes” to confirm.

- All temporary files will now be deleted.

Where do I find shellbags in Windows 7?

For Windows 7 and later, shellbags are also found in the UsrClass.dat hive: The shellbags are structured in the BagMRU key in a similar format to the hierarchy to which they are accessed through Windows Explorer with each numbered folder representing a parent or child folder of the one previous.

What are the shellbag keys in Windows Registry?

As Windows Registry artifacts go, the “Shellbag” keys tend to be some of the more complicated artifacts we have to decipher. But they are worth the effort, giving an excellent means to prove the existence of files and folders along with user knowledge.

How are the shellbags organized in Windows Explorer?

The shellbags are structured in the BagMRU key in a similar format to the hierarchy to which they are accessed through Windows Explorer with each numbered folder representing a parent or child folder of the one previous.

What do you need to know about shellbags?

In oversimplified terms, it is used to record configuration information from user processes that do not have access to write to the standard registry hives. In order to get all Shellbags information, we now need to parse both NTUSER.da t and USRCLASS.dat for each user account.

Microsoft Windows uses a set of Registry keys known as “shellbags” to maintain the size, view, icon, and position of a folder when using Explorer. These keys are useful to a forensic investigator. Shellbags persist information for directories even after the directory is removed, which means that they can be used to enumerate past mounted volumes, deleted files, and user actions.

Yuandong Zhu, Pavel Gladyshev, and Joshua James provided a nice overview of the investigative value of shellbags in “Using shellbag information to reconstruct user activities” [pdf]; however, they do not describe how to programmatically access the data. Allan S Hay went into greater detail in his December, 2004 document “MiTeC Registry Analyser” [pdf], although he also leaves out a thorough analysis of the format. TZWorks provides an effective closed-source shellbag parser sbag, but does not explain its algorithm. Yogesh Khatri first described the basic structure of Windows Shell Items in his blog post for 42 LLC entitled Shell BAG Format Analysis. Joachim Metz went on to described the binary format of the Windows Shell Item structures with great detail in Windows Shell Item format specification [pdf]. This page documents an approach to parsing shellbags in detail, as well as introduces an open-source, cross-platform shellbag parser.

Shellbag locations

Shellbags may be found in a few locations, depending on operating system version and user profile. On a Windows XP system, shellbags may be found under:

HKEY\_USERS\{USERID}\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Shell\HKEY\_USERS\{USERID}\Software\Microsoft\Windows\ShellNoRoam\

The NTUser.dat hive file persists the Registry key HKEY\_USERS\{USERID}\.

On a Windows 7 system, shellbags may be found under:

HEKY\_USERS\{USERID}\Local Settings\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Shell\

The UsrClass.dat hive file persists the registry key HKEY\_USERS\{USERID}\.

Shellbag Parsing

Let us begin with the Shell\ key. The Shell\ key does not have any values. Under the Shell\ key are two keys: Shell\Bags\ and Shell\BagMRU\.

FOLDERDATA

Each subkey under Shell\Bags\ is named as increasing integers from one, such as Shell\Bags\1\ or Shell\Bags\2\. Let us call these subkeys FOLDERDATA, since they each represent one item viewed in Explorer, and this is usually a folder. FOLDERDATA subkeys do not have any values, but often have subkeys. The most common subkey is Shell\Bags\{Int}\Shell\, but there are a few other possibilities (ComDlg, Desktop, etc.). The subkeys under a FOLDERDATA describe the settings, position, and icon when viewing the folder in Explorer. In particular, a Registry value whose name begins with ItemPos specifies the location of the icons for a given desktop resolution. For example, on my Windows 7 system, the Registry key HKEY\_USERS\{USERID}\Local Settings\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Shell\Bags\6\Shell\{5C4F28B5-F869-4E84-8E60-F11DB97C5CC7} has 12 values that record various configurations. This set includes the value ItemPos1427x820(1) that has type REG_BIN with length 0x120:

0000 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

0010 15 00 00 00 51 00 00 00 14 00 1F 60 40 F0 5F 64 ....Q......`@._d

0020 81 50 1B 10 9F 08 00 AA 00 2F 95 4E 15 00 00 00 .P......./.N....

0030 A0 00 00 00 46 00 3A 00 02 02 00 00 10 3D 0C 8E ....F.:......=..

0040 20 00 43 79 67 77 69 6E 2E 6C 6E 6B 00 00 2C 00 .Cygwin.lnk..,.

0050 03 00 04 00 EF BE 10 3D 0C 8E 10 3D 0C 8E 14 00 .......=...=....

0060 00 00 43 00 79 00 67 00 77 00 69 00 6E 00 2E 00 ..C.y.g.w.i.n...

0070 6C 00 6E 00 6B 00 00 00 1A 00 15 00 00 00 02 00 l.n.k...........

0080 00 00 5A 00 3A 00 42 06 00 00 10 3D 91 7C 20 00 ..Z.:.B....=.| .

0090 4D 4F 5A 49 4C 4C 7E 31 2E 4C 4E 4B 00 00 3E 00 MOZILL~1.LNK..>.

00A0 03 00 04 00 EF BE 10 3D 91 7C 10 3D 61 85 14 00 .......=.|.=a...

00B0 00 00 4D 00 6F 00 7A 00 69 00 6C 00 6C 00 61 00 ..M.o.z.i.l.l.a.

00C0 20 00 46 00 69 00 72 00 65 00 66 00 6F 00 78 00 .F.i.r.e.f.o.x.

00D0 2E 00 6C 00 6E 00 6B 00 00 00 1C 00 41 01 00 00 ..l.n.k.....A...

00E0 51 00 00 00 30 00 31 00 00 00 00 00 10 3D 2C 81 Q...0.1......=,.

00F0 10 00 4D 49 52 00 1E 00 03 00 04 00 EF BE 10 3D ..MIR..........=

0100 B0 80 10 3D A7 8C 14 00 00 00 4D 00 49 00 52 00 ...=......M.I.R.

0110 00 00 12 00 41 01 00 00 51 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ....A...Q.......With no tools beyond Regedit (or Regview.py), Windows 8.3 filenames (eg. MOZILL\~1.LNK) and Unicode filenames (eg. Mozilla Firefox.lnk) stand out. Fortunately, by applying the formats found in Joachim’s paper, more details can be extracted. Throughout this document, I refer to this Registry value type as an ITEMPOS value.

ITEMPOS values

The ITEMPOS value’s structure is a list of Windows File Entry Shell Items (SHITEM_FILEENTRY) terminated by an entry whose size field is zero. The list begins at offset 0x10. Items are preceeded by 0x8 bytes whose meaning is unknown. The minimum size of a SHITEM_FILEENTRY structure is 0x15 bytes, so entries whose size field is less than 0x15 should be skipped. The valid SHITEM_FILEENTRY items have the following structure (in pseudo-C / 010 Editor template format):

typedef struct SHITEM_FILEENTRY {

UINT16 size;

UINT16 flags;

UINT32 filesize;

DOSDATE date;

DOSTIME time;

FILEATTR16 fileattrs;

string short_name;

if (offset() % 2 != 0) {

UINT8 alignment;

}

UINT16 ext_size;

UINT16 ext_version;

if (ext_version >= 0x0003) {

UINT16 unknown0; // == 0x0004

UINT16 unknown1; // == 0xBEEF

DOSDATE creation_date;

DOSTIME creation_time;

DOSDATE access_date;

DOSTIME access_time;

UINT32 unknown2;

}

if (ext_version >= 0x0007) {

FILEREFERENCE file_ref;

UINT64 unknown3;

UINT16 long_name_size;

if (ext_version >= 0x0008) {

UINT32 unknown4;

}

wstring long_name;

if (long_name_size > 0) {

wstring long_name_addl;

}

}

else if (ext_version >= 0x0003) {

wstring long_name;

}

if (ext_version >= 0x0003) {

UINT16 unknown5;

}

UINT8 padding[size - (offset() - offset(size)];

} SHITEM_FILEENTRY;FILEREFERENCE is a 64bit MFT file reference structure (48 bits file MFT record number, 16 bits MFT sequence number). FILEATTRS is a 16 bit set of flags that specifies attributes such as if the item is read-only or a system file. Applying this template to the ITEMPOS Registry value, we see there are four list items: one invalid entry, and three SHITEM_FILEENTRY items.

00 00 00 00 --> header/footer 00 00 00 00 --> unknown padding (item position?) 00 00 00 00 --> invalid SHITEM_FILEENTRY 00 00 00 00 --> SHITEM_FILEENTRY 0000 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................ 0010 15 00 00 00 51 00 00 00 14 00 1F 60 40 F0 5F 64 ....Q......`@._d 0020 81 50 1B 10 9F 08 00 AA 00 2F 95 4E 15 00 00 00 .P......./.N.... 0030 A0 00 00 00 46 00 3A 00 02 02 00 00 10 3D 0C 8E ....F.:......=.. 0040 20 00 43 79 67 77 69 6E 2E 6C 6E 6B 00 00 2C 00 .Cygwin.lnk..,. 0050 03 00 04 00 EF BE 10 3D 0C 8E 10 3D 0C 8E 14 00 .......=...=.... 0060 00 00 43 00 79 00 67 00 77 00 69 00 6E 00 2E 00 ..C.y.g.w.i.n... 0070 6C 00 6E 00 6B 00 00 00 1A 00 15 00 00 00 02 00 l.n.k........... 0080 00 00 5A 00 3A 00 42 06 00 00 10 3D 91 7C 20 00 ..Z.:.B....=.| . 0090 4D 4F 5A 49 4C 4C 7E 31 2E 4C 4E 4B 00 00 3E 00 MOZILL~1.LNK..>. 00A0 03 00 04 00 EF BE 10 3D 91 7C 10 3D 61 85 14 00 .......=.|.=a... 00B0 00 00 4D 00 6F 00 7A 00 69 00 6C 00 6C 00 61 00 ..M.o.z.i.l.l.a. 00C0 20 00 46 00 69 00 72 00 65 00 66 00 6F 00 78 00 .F.i.r.e.f.o.x. 00D0 2E 00 6C 00 6E 00 6B 00 00 00 1C 00 41 01 00 00 ..l.n.k.....A... 00E0 51 00 00 00 30 00 31 00 00 00 00 00 10 3D 2C 81 Q...0.1......=,. 00F0 10 00 4D 49 52 00 1E 00 03 00 04 00 EF BE 10 3D ..MIR..........= 0100 B0 80 10 3D A7 8C 14 00 00 00 4D 00 49 00 52 00 ...=......M.I.R. 0110 00 00 12 00 41 01 00 00 51 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ....A...Q.......

Taking the first valid entry from offset 0x34, let’s parse out the fields from the binary. The following block visually maps out the relevant bytes, while the table translates each field into a human readable value.

00 00 00 00 --> SHITEM_FILEENTRY size 00 00 00 00 --> filesize 00 00 00 00 --> timestamp 00 00 00 00 --> filename 0000 46 00 3A 00 02 02 00 00 10 3D 0C 8E 20 00 43 79 F.:.....w.=.Ž Cy 0010 67 77 69 6E 2E 6C 6E 6B 00 00 2C 00 03 00 04 00 gwin.lnk..,..... 0020 EF BE 10 3D 0C 8E 10 3D 0C 8E 14 00 00 00 43 00 ï¾.=.Ž.=.Ž....C. 0030 79 00 67 00 77 00 69 00 6E 00 2E 00 6C 00 6E 00 y.g.w.i.n...l.n. 0040 6B 00 00 00 1A 00 k.....

| Offset | Field | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 0x00 | ITEMPOS size | 0x46 |

| 0x04 | Filesize | 0x202 |

| 0x08 | Modified Date | August 16, 2010 at 17:48:24 |

| 0x0E | 8.3 Filename | Cygwin.lnk |

| 0x22 | Created Date | August 16, 2010 at 17:48:24 |

| 0x26 | Modified Date | August 16, 2010 at 17:48:24 |

| 0x2E | Unicode Filename | Cywgin.lnk |

At this point, it is easy to write parser that explores the FOLDERDATA keys under the Shell registry key. For each FOLDERDATA, the parser might enumerate each ITEMPOS value and consider the binary blob. By applying the binary template above, the tool could identify filenames, MACB timestamps, and other metadata independent of the filesystem MFT. Unfortunately, we’re still missing a key piece of information: the full file path.

BagMRU tree

To recover file paths from Shellbags, we’ll need to consider the Registry keys under BagMRU. The subkeys under Shell\BagMRU form a recursive, tree-like structure that mirrors the file system on disk. Shell\BagMRU is the root of the tree. Each subkey is a node representing a folder, and like a folder, may contain children nodes. Yet, unlike (most) folders, the nodes are named as increasing integers from zero. For example, the branch Shell\BagMRU\0 might have the children 0, 1, and 2.

All nodes in this tree have a value named MRUListEx, and many have a value named NodeSlot. NodeSlot is what interests us, as it forms the link between the filesystem tree structure and the FOLDERDATA keys. A NodeSlot value has type REG_DWORD and should be interpreted as a pointer to the FOLDERDATA key with the same name. For example, on my workstation, the key Shell\BagMRU\1\1\3\0 has a NodeSlot value of

- This means that the FOLDERDATA

Shell\Bags\144\corresponds to a folder with a path of four components. What are they? The components are described by the values atShell\BagMRU\1,Shell\BagMRU\1\1,Shell\BagMRU\1\1\3, andShell\BagMRU\1\1\3\0.

SHITEMLIST

In addition to the values MRUListEx and NodeSlot, nodes of the Shell\BagMRU tree have one value for each subkey. The values have the same name as the subkey; since the subkeys are named as increasing integers, so are the values. Each value records metadata about the filesystem path component associated with the subkey. The values have type REG_BIN, and have an internal binary structure known as an SHITEMLIST. An SHITEMLIST is formed by contiguous items terminated by an empty item. Practically, though, the SHITEMLIST of a BagMRU node will have two entries: a relevant entry, and the empty terminator item. The first word of each SHITEM gives the item’s size.

Joachim’s paper on Window’s shell items is the best resource for understanding the variations among SHITEM entries. From a high level, there are at least ten types of items that range from SHITEM_FILEENTRY and SHITEM_FOLDERENTRY to SHITEM_CONTTROLPANELENTRY. For each of these types, we can extract at least a path component such as “My Documents” or “\myserver”. Fortunately, most items have type SHITEM_FOLDERENTRY, which provides additional metadata including MAC timestamps. A small number of items do not conform to the known structure, although these do not usually contain any human readable strings or hints.

Putting it all together

With the SHITEMLIST structure in hand, we now have enough information to comprehensively parse Windows shellbags. To do this, first recurse down the Shell\BagMRU keys while complete directory paths. At each node, record any available metadata and lookup the associated FOLDERDATA. Recall that the FOLDERDATA may indicate some of the items contained by the directory, so record this metadata, too. Finally, format and enjoy!

The following code block lists the algorithm in a Pythonish language for the programmers in the room.

def get_shellbags():

shellbags = []

bagmru_key = shell_key.subkey("BagMRU")

bags_key = shell_key.subkey("Bags")

def shellbag_rec(key, bag_prefix, path_prefix):

"""

Function to recursively parse the BagMRU Registry key structure.

Arguments:

`key`: The current 'BagsMRU' key to recurse into.

`bag_prefix`: A string containing the current subkey path of

the relevant 'Bags' key. It will look something like '1\2\3\4'.

`path_prefix` A string containing the current human-readable,

file system path so far constructed.

Returns:

A list of paths to filesystem artifacts

"""

# First, consider the current key, and extract shellbag items

slot = key.value("NodeSlot").value()

# Look at ..\Shell, and ..\Desktop, etc.

for bag in bags_key.subkey( slot ).subkeys():

# Only consider ITEMPOS keys

for value in [value for value in bag.values() if \

"ItemPos" in value.name()]:

# Call our binary processing code to extract items

new_items = process_itempos(value)

for item in new_items:

shellbags.append(path_prefix + item.path)

# Next, recurse into each subkey of this BagMRU node (1, 2, 3, ...)

for value in value for value in key.values():

# Call our binary processing code to extract item

new_item = process_bag(value)

shellbags.append(path_prefix + new_item.path)

shellbag_rec(key.subkey( value.name() ),

bag_prefix + "\" + value.name(),

new_item.path )

shellbag_rec("HKEY_USERS\{USERID}\Software\Microsoft\Windows\ShellNoRoam",

"",

"")

return shellbagsShellbags.py

Using these concepts, I’ve implemented a cross-platform shellbag parser for Windows XP and greater in the Python programming language. The code is freely available here, so all algorithms and structures are accessible to interested parties. I’ve licensed the code under the Apache 2.0 license, so please feel encouraged to take and improve the routines as you feel fit. As a benchmark, shellbags.py tends to identify at least the items returned by the sbag utility, and in some cases returns more.

Shellbags.py accepts the path to a raw Registry hive acquired forensically as a command line argument. To ensure interoperability, output is formatted according to the Bodyfile specification by default. The following block lists a demonstration of me running shellbags.py against a Windows XP NTUSER.dat Registry hive.

$ python shellbags.py ~/projects/registry-files/willi/xp/NTUSER.DAT.copy0

...

0|\My Documents (Shellbag)|0|0|0|0|0|978325200|978325200|18000|978325200

0|\My Documents\Downloads (Shellbag)|0|0|0|0|0|1282762334|1282762334|18000|1281987456

0|\My Documents\My Dropbox (Shellbag)|0|0|0|0|0|1281989096|1282762296|18000|1281989050

0|\My Documents\My Music (Shellbag)|0|0|0|0|0|1281995426|1282239780|18000|1281987154

0|\My Documents\My Pictures (Shellbag)|0|0|0|0|0|1281995426|1282239780|18000|1281987152

0|\My Documents\My Dropbox (Shellbag)|0|0|0|0|0|978325200|978325200|18000|978325200

0|\My Documents\My Dropbox\Tools (Shellbag)|0|0|0|0|0|1281989092|1281989092|18000|1281989088

0|\My Documents\My Dropbox\Tools\Windows (Shellbag)|0|0|0|0|0|1281989140|1281989140|18000|1281989092

0|\My Documents\My Dropbox\Tools\Windows\7zip (Shellbag)|0|0|0|0|0|1281993604|1284668784|18000|1281989140

0|\My Documents\My Dropbox\Tools\Windows\Adobe (Shellbag)|0|0|0|0|0|1281994956|1284668784|18000|1281989140

0|\My Documents\My Dropbox\Tools\Windows\Bitpim (Shellbag)|0|0|0|0|0|1281994656|1284668784|18000|1281989140

...To improve readability, I ran the output through the mactime utility to generate a timeline of activity. The following block lists a portion of this sample.

...

Fri Jun 10 2011 14:09:02 0 m... 0 0 0 0 \My Documents\My Dropbox\Tools\Windows\Mandiant Highlighter (Shellbag)

Fri Jun 10 2011 16:09:56 0 m... 0 0 0 0 \My Documents\My Dropbox\Tools\Windows\Mandiant Highlighter\MandiantHighlighter1.0.1.msi (Shellbag)

Fri Jun 10 2011 16:10:18 0 ...b 0 0 0 0 \My Documents\My Dropbox\Tools\Windows\Mandiant Highlighter\MandiantHighlighter1.1.2.msi (Shellbag)

Fri Jun 10 2011 16:10:36 0 ma.. 0 0 0 0 \My Documents\My Dropbox\Tools\Windows\Mandiant Highlighter\MandiantHighlighter1.1.2.msi (Shellbag)

Fri Jun 10 2011 18:20:48 0 m... 0 0 0 0 \My Computer\{00020028-0000-0041-6400-6d0069006e00}\My Dropbox\Tools\Windows\Mandiant Malware INfo (Shellbag)

Fri Jun 10 2011 18:20:50 0 m... 0 0 0 0 \My Documents\My Dropbox\Tools\Windows\FTK\Imager_Lite_ 2.9.0 (Shellbag)

Fri Jun 10 2011 21:06:44 0 ...b 0 0 0 0 \My Computer\C:\Documents and Settings\Administrator\Desktop\IOCs\custom (Shellbag)

Fri Jun 10 2011 22:43:14 0 m... 0 0 0 0 \My Computer\C:\Documents and Settings\Administrator\Desktop\IOCs\new (Shellbag)

Fri Jun 10 2011 22:52:02 0 m... 0 0 0 0 \My Documents\My Dropbox\Tools\Windows\FTK (Shellbag)

...Help

For reference, the following code block lists the command line parameters accepted by shellbags.py. Now get going and try it out!

usage: shellbags.py [-h] [-v] [-p] file [file ...]

Parse Shellbag entries from a Windows Registry.

positional arguments:

file Windows Registry hive file(s)

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-v Print debugging information while parsing

-p If debugging messages are enabled, augment the formatting with

ANSI color codes