Раскрывать тему параллельного или асинхронного программирования непросто. Во-первых, она перегружена терминологией и трудна для понимания. Как правило, тонкости и особенности работы с языками усваиваются, лишь когда столкнешься с ними на практике. Во-вторых, в контексте Python тоже много своих подводных камней. Но сегодня почти любой современный web-сервис сталкивается с необходимостью многопоточности или асинхронности. Поскольку это многопользовательская среда, мы хотим направить всю процессорную мощность не на ожидание, а на решение прикладных задач бизнеса, чтобы все пользователи вовремя получили необходимые данные.

Эта статья будет полезна тем разработчикам, которые хотят выполнять больше работы за одно и то же время, и задействовать все ресурсы своего железа. Проще говоря, делать больше, и при этом обходиться меньшими ресурсами. Пусть железо работает, а не простаивает.

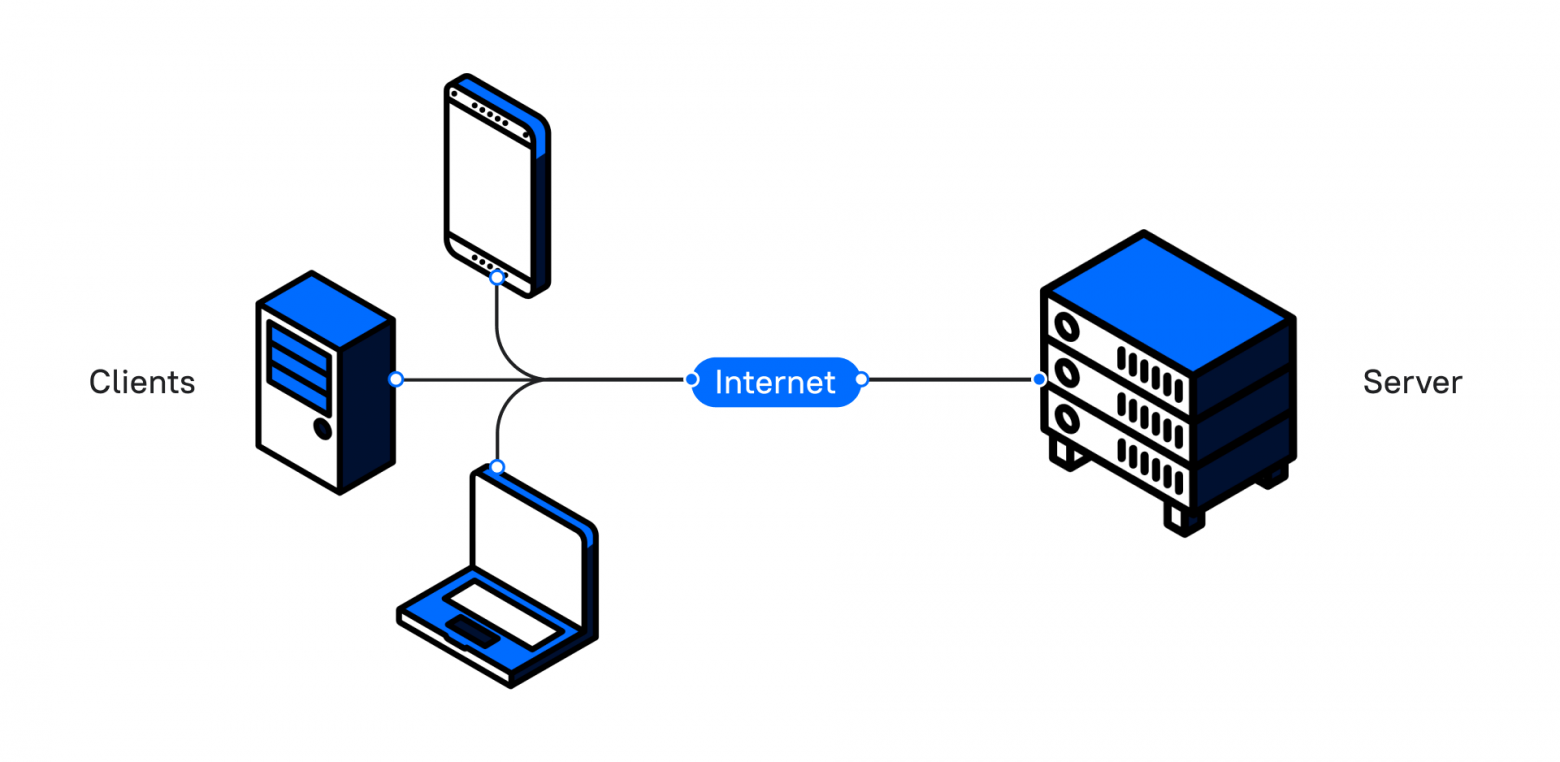

Давайте возьмем за отправную точку ситуацию, когда у нас есть приложение, которое работает по стандартной схеме клиент – сервер:

Клиент посылает запрос и получает ответ. А теперь представьте, что в нашем приложении есть кнопка, которая формирует большой отчет. Когда пользователь нажимает на нее, программа долго обрабатывает запрос. Клиент ждет ответа, и пока отчет не будет сформирован, он не сможет пользоваться интерфейсом приложения.

Как мы можем помочь пользователю продолжить взаимодействие с нашим приложением, пока формируется отчет? Мы можем создать отдельный процесс, отдельный поток, и выполнять код асинхронно.

Рассмотрим каждое понятие отдельно.

Процессы

Процессы являются контейнерами. Их основная задача – изолировать программы друг от друга, чтобы одна не могла получить доступ к памяти другой.

В контексте Python каждому процессу выделен свой интерпретатор. Когда мы запускаем несколько процессов из кода, то мы обнаруживаем такое же количество процессов в мониторинге системы.

Небольшой пример создания процессов:

from multiprocessing import Process

def print_word(word):

print('hello,', word)

if __name__ == '__main__':

p1 = Process(target=print_word, args=('bob',), daemon=True)

p2 = Process(target=print_word, args=('alice',), daemon=True)

p1.start()

p2.start()

p1.join()

p2.join()Процессы представлены как экземпляр класса Process из встроенной библиотеки multiprocessing.

У нас есть функция, которая принимает 1 параметр и печатает приветствие с переданным параметром. Внутри конструкции if мы создаем два процесса p1 и p2 в качестве параметров, то есть мы передаем:

target – с названием выполняемой функции,

args – параметры для функции, которую мы будем вызывать,

daemon – с флагом True, который говорит нам, что процесс будет являться «демоном» – об этом чуть позже.

Для того чтобы процесс стартовал, мы вызываем у каждого метод .start().

Но ниже мы вызываем еще и метод .join().

Для чего нужен join() и что такое daemon? Или основные и фоновые процессы

У нас есть основной (главный) процесс, который содержит весь код нашей программы, и два дополнительных (фоновых) p1, p2. Их мы создаем, когда мы прописываем параметр daemon=True. Так мы как раз и указываем, что эти два процесса будут второстепенными. Если мы не вызовем метод join у фонового процесса, то наша программа завершит свое выполнение, не дожидаясь выполнения p1 и p2.

Немного теории о процессах

Процессы не могут работать параллельно на одноядерной машине.

Параллельное вычисление – выполнение двух и более задач одновременно, когда каждое ядро процессора берет задачу и выполняет ее. На многоядерной машине параллельное вычисление – нормальная практика. Однако количество ядер у нас ограничено, причем весьма сильно, а процессов в системе работает много.

Познакомимся с еще одним термином — вытесняющая многозадачность.

Вытесняющая многозадачность — это такой способ управления задачами, при котором решение о переключении процессора с выполнения одного процесса на выполнение другого принимается планировщиком операционной системы.

Предположим, что у нас одноядерный процессор и ему приходится выполнять работу множества программ одновременно. Как он это делает?

В этом случае каждой программе выделяется небольшой промежуток времени, то есть программы конкурируют за доступ к ядру. Процессор сам переключает контекст выполнения, и таким образом создается впечатление, что программы работают одновременно. Но это не совсем так.

Проще говоря, одна программа поработала какое-то время, и процессор переключает контекст на другую, чтобы она выполнила запланированные действия, передала обратно и так далее.

Когда количество процессов превышает количество ядер, на помощь приходит конкурентное вычисление.

Потоки

Первое, о чем хотим сказать про потоки — интерфейсы работы с процессами и потоками в Python очень похожи.

Потоки живут внутри процессов, потребляют меньше ресурсов и разделяют общую память внутри процесса. Во многих языках программирования потоки создавались именно для того, чтобы выполнять задачи параллельно, но не в Python. А виноват в этом GIL.

GIL (Global interpreter lock) следит за тем, чтобы в один момент времени работал лишь один поток. Механизм похож на то, как процессы конкурируют за ядро. Но в отличие от процессов GIL освобождается при вызове блокирующей функции операций ввода/вывода. Другой механизм его освобождения – time.sleep(). Об этом позже.

import threading

def greet(name):

print('hello: ', name)

if __name__ == '__main__':

t1 = threading.Thread(target=greet, args=('bob',), daemon=True)

t2 = threading.Thread(target=greet, args=('alice',), daemon=True)

t1.start()

t2.start()

t1.join()

t2.join()Как видно, процесс создания потоков идентичен алгоритму формирования процессов.

Теперь, когда мы познакомились с основными понятиями, продемонстрируем несколько проблем, которые встречаются в многопоточном программировании.

Первая проблема – Race Condition или состояние гонки.

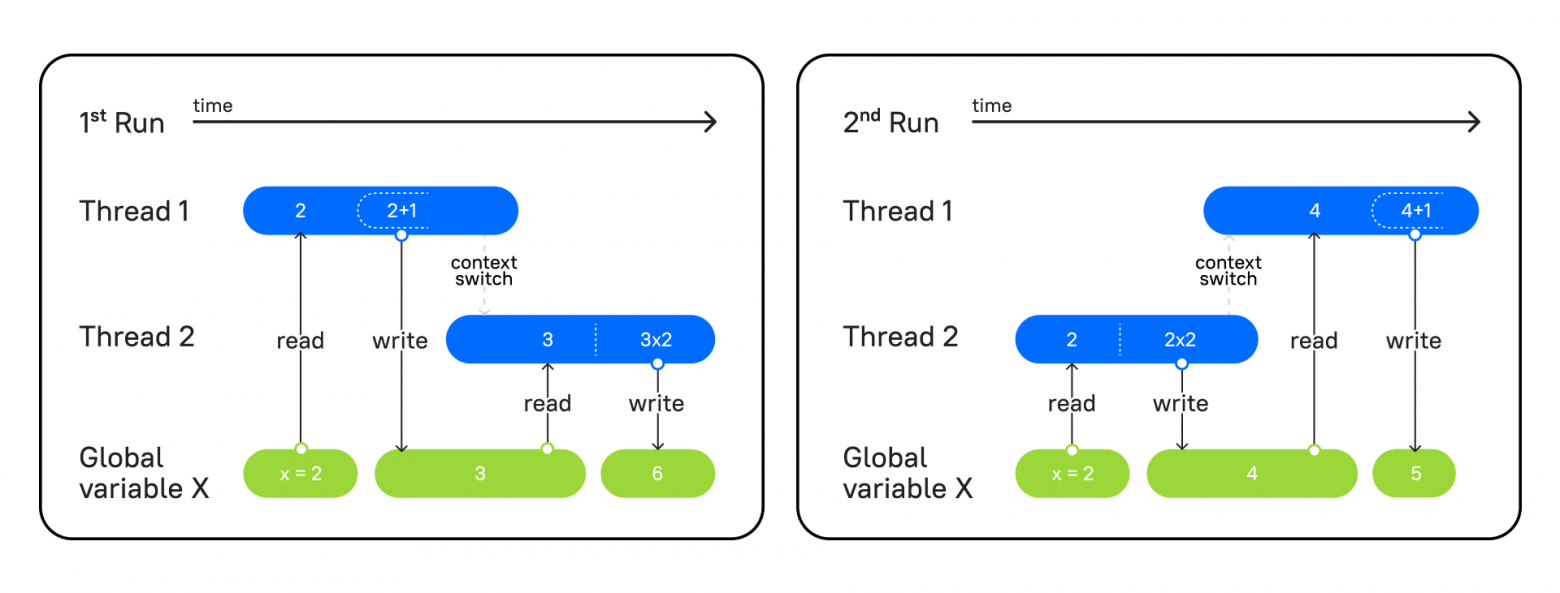

На изображении мы видим два запуска одной и той же программы, в которой есть два потока: в первом функция увеличивает переданное число на единицу, а во втором — мы умножаем число на 2.

Слева вы видите первый запуск программы. Первый поток берет значение из глобальной переменной x, прибавляет 1 и записывает в x результат = 3. Затем второй поток начинает работу. Он берет из переменной x значение 3, умножает на 2 и записывает результат = 6.

На правой схеме – второй запуск программы, где сперва в работу вступает поток 2, он выполняет те же операции, берет x = 2, умножает на 2 и фиксирует результат 4. Затем вступает поток 1, читает 4 из x, увеличивает на единицу и записывает 5.

Так как оба потока меняли порядок работы программы, но выполняли ее по очереди, у нас не возникало никакого конфликта, и мы получали ожидаемый результат.

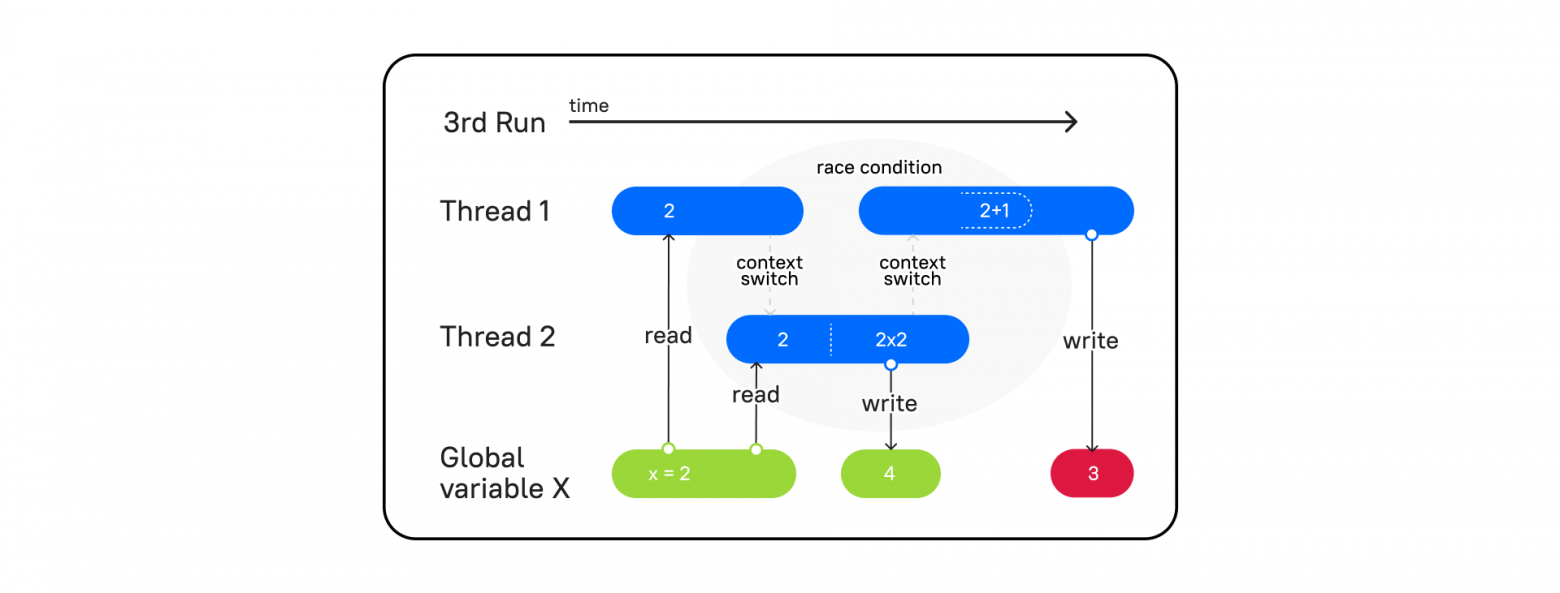

Но давайте посмотрим на такой поток выполнения:

Поток 1 вступает в работу, читает переменную x и переключает контекст на поток 2 (context switch). Затем поток 2 берет значение из x = 2, умножает на 2 и записывает в x = 4. Процессор переключает контекст на поток 1, а в потоке 1, как мы помним, сохранено значение x = 2. В итоге он увеличивает значение на единицу и записывает в x = 3, а значит, на выходе мы получаем 3.

Один поток обогнал другой при переключении контекста, и мы получили непредсказуемый результат. Такое событие называется Race condition. Как тогда быть уверенным в том, что поток, взявший в работу какие-то данные, выполнит свою работу, перед тем как переключит свой контекст на другой потоку?

Вот пример:

```

from threading import Thread

from time import sleep

counter = 0

def increase(by):

global counter

local_counter = counter

local_counter += by

sleep(0.1)

counter = local_counter

print(f'{counter=}')

t1 = Thread(target=increase, args=(10,))

t2 = Thread(target=increase, args=(20,))

t1.start()

t2.start()

t1.join()

t2.join()

```Посмотрим на результат:

```

counter=10

counter=20

```Вместо 30 получаем 20.

На помощь нам может прийти такое понятие как Lock.

Lock (замок) – объект, который захватывает поток, и пока поток не освободит (release) Lock, другие потоки не смогут ничего сделать с этими данными, захваченными при помощи замка.

```

from threading import Thread, Lock

from time import sleep

counter = 0

def increase(by, lock: Lock):

global counter

lock.acquire()

local_counter = counter

local_counter += by

sleep(0.1)

counter = local_counter

print(f'{counter=}')

lock.release()

lock = Lock()

t1 = Thread(target=increase, args=(10, lock,))

t2 = Thread(target=increase, args=(20, lock,))

t1.start()

t2.start()

t1.join()

t2.join()

```Вот теперь как и должно быть:

```

counter=10

counter=30

```Несмотря на то, что Lock помогает решить проблему с Race condition, он может привести к другой сложной ситуации, когда один поток ждет освобождение одного замка, а другой ждет освобождение от первого. Такое ожидание приводит к ситуации взаимного тупика, известного как Deadlock.

```

from threading import Thread, Lock

from time import sleep

a = 5

b = 10

a_lock = Lock()

b_lock = Lock()

def function_a():

global a

global b

a_lock.acquire()

print('Функция a, a_lock = заблокирован')

sleep(1)

b_lock.acquire()

print('Функция a, b_lock = заблокирован')

sleep(1)

a_lock.release()

print('Функция a, a_lock = разблокирован')

b_lock.release()

print('Функция a, b_lock = разблокирован')

def function_b():

global a

global b

b_lock.acquire()

print('Функция b, b_lock = заблокирован')

a_lock.acquire()

print('Функция b, a_lock = заблокирован')

sleep(1)

b_lock.release()

print('Функция b, b_lock = разблокирован')

a_lock.release()

print('Функция b, a_lock = разблокирован')

t1 = Thread(target=function_a)

t2 = Thread(target=function_b)

t1.start()

t2.start()

t1.join()

t2.join()

print('Готово')

```И теперь посмотрим результат:

```

Функция a, a_lock = заблокирован

Функция b, b_lock = заблокирован

```Наша программа зависает в ожидании разблокировки, которая никогда не произойдет. Так же Deadlock произойдет при попытке заблокировать наш Lock повторно в том же потоке.

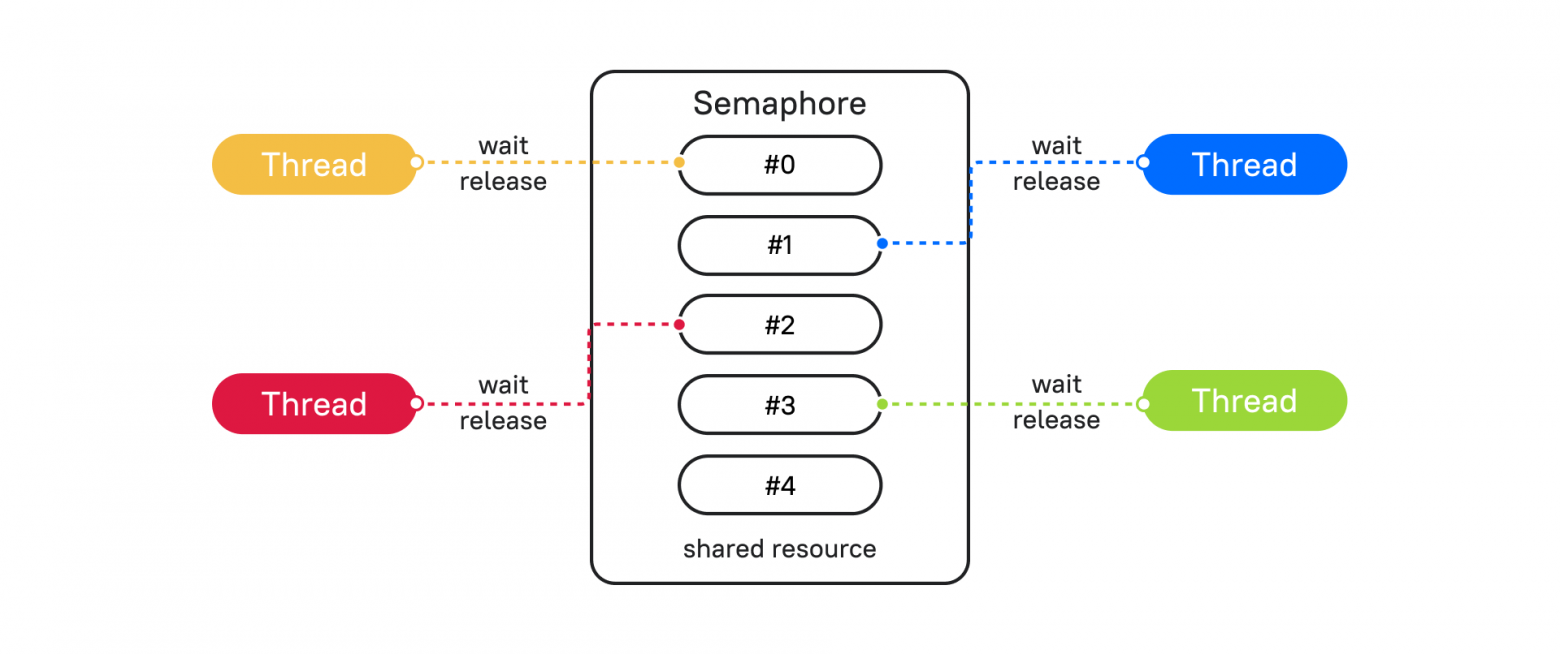

Решить проблему с Deadlock могут помочь различные механизмы синхронизации потоков. Разберем один из таких примеров – Semaphore (Семафор).

Semaphore прост в понимании, если его представить в виде объекта, который ограничивает выполнение блока кода установленным количеством, по умолчанию это 1. При каждом вхождении в блок кода Semaphore счетчик уменьшается. Если счетчик дошел до 0, все потоки блокируются, и пока поток не освободит семафор, другие будут ждать разрешения подключиться.

Посмотрим Semaphore на примере реализации очереди из реального кейса.

```

import datetime

from threading import Semaphore, Thread

from time import sleep

s = Semaphore(3)

def semaphore_func(payload: int):

s.acquire()

now = datetime.datetime.now().strftime('%H:%M:%S')

print(f'{now=}, {payload=}')

sleep(2)

s.release()

threads = [Thread(target=semaphore_func, args=(i,)) for i in range(7)]

for t in threads:

t.start()

for t in threads:

t.join()

```

В результате увидим, что функция выполнялась группами по 3 потока. То есть одновременно не может выполняться кусок кода с блокировкой через Semaphore больше, чем указан в инициализации класса Semaphore. Видим паузы в 2 секунды между блокировками.

```

now='00:49:51', payload=0

now='00:49:51', payload=1

now='00:49:51', payload=2

now='00:49:53', payload=3

now='00:49:53', payload=5

now='00:49:53', payload=4

now='00:49:55', payload=6

```Это удобно использовать, например, в таком виде: если база данных может держать не более 30 соединений, то инстанциируем Semaphore со значением 30. Блокируем, когда поднимаем соединение и разблокируем, когда освобождаем.

Есть несколько способов синхронизации потоков, которые подходят для тех или иных ситуации. Примеры можно посмотреть в документации.

Теперь поговорим об освобождении GIL.

CPython управляет памятью с помощью подсчета ссылок. То есть для каждого объекта Python подсчитывается, сколько на него указывается ссылок с других объектов, использующих его в данный момент. При добавлении ссылки счетчик увеличивается, при удалении ссылки счетчик уменьшается. А когда счетчик ссылок становится 0 — это означает, что объект больше не нужен, и его можно удалить из памяти.

Следовательно, если не будет GIL, который запрещает Python процессу выполнять более одной команды байт-кода в каждый момент времени, то при подсчете ссылок может случиться Race-condition, с подсчетом ссылок на объекты, как это было в примере с переменными выше.

Итак, раз GIL запрещает одновременное выполнение Python кода, из этого следует, что он высвобождается, когда Python код не выполняется. Когда мы ждем, например, пока считается файл с диска или придет ответ на запрос к сайту. Так как в этом случае низкоуровневые системные вызовы работают за пределами Python кода и среды выполнения, и код операционной системы не взаимодействует напрямую с объектами Python, соответственно, они не увеличивают и не уменьшают счетчик ссылок. GIL захватывается снова, когда данные переносятся в объект Python.

Стало быть, если мы сделаем библиотеку, даже с CPU-bound нагрузкой, где мы не взаимодействуем с объектами Python (словарями, списками, целыми числами и т. д.) или большая часть библиотеки не взаимодействует, то мы можем освободить GIL. Например, библиотеки hashlib и NumPy выполняют расчеты на чистом C и освобождают GIL.

time.sleep() — реализация этой функции освобождает GIL и выполняется на уровне системы и работает вне кода Python.

Как видите, в многопоточности существует огромное количество нюансов и проблем. В реальных больших программах будет непросто понять, где происходит ошибка. Рассмотрим, как можно распараллелить выполнение программ. В этом поможет асинхронность.

Асинхронность

Для того чтобы лучше понять асинхронность, окунемся в далекий 1992 год. Тогда была выпущена операционная система Windows 3.1 которая использовала кооперативную многозадачность.

Кооперативная многозадачность — это тип многозадачности, при котором фоновые задачи выполняются только во время простоя основного процесса и только в том случае, если на это получено разрешение основного процесса.

То есть время, когда исполняемая программа управляет передачей управления другому процессу и передачей процессорного времени.

Недостатком такого исполнения является то, что если одна задача зависла. Зависает вся система.

А вот преимущества такого решения: разработчик программы отдает управление тогда, когда он посчитает это нужным.

Теперь мы подобрались к понятию асинхронного программирования.

Асинхронное программирование — выполнение программы в неблокирующем режиме системного вызова, что позволяет потоку программы продолжить работу.

Благодаря асинхронному программированию в одном процессе и даже потоке мы можем выполнять сразу множество задач. Как же это происходит?

В реальном программировании, а особенно в web-разработке мы очень часто чего-то ждём и не делаем полезной работы. Вот несколько примеров:

-

Отправили запрос на сторонний ресурс и ждем ответа.

-

Отправили запрос в базу данных и ждем результата запроса.

-

Читаем или записываем файл на диск.

-

И так далее.

Получается что мы ждем, ждем и ждем. А в это время наша программа могла бы выполнить множество полезной нагрузки. И мы как разработчики ПО точно знаем, где мы будем ожидать. Ничего не напоминает? Да! Похоже на кооперативную многозадачность, но только не на уровне операционной системы, а на уровне процесса.

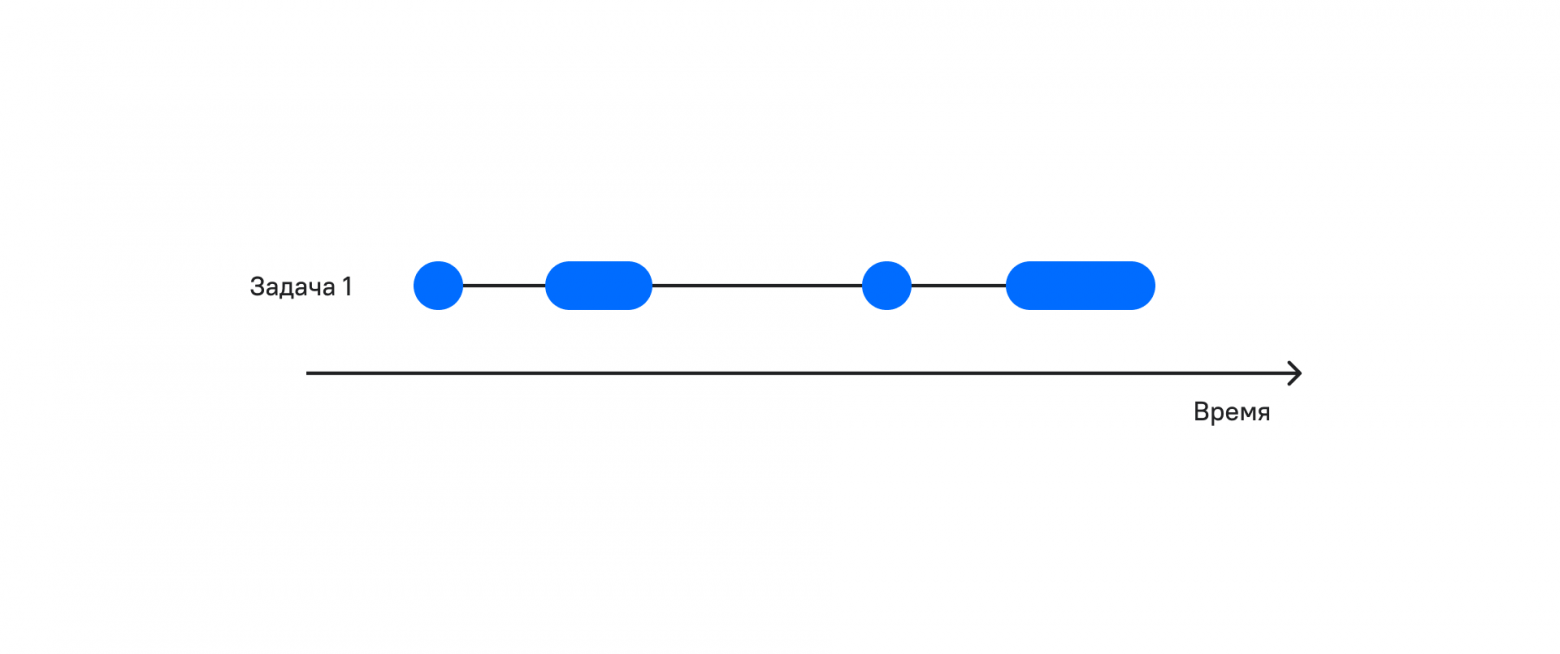

На рисунке видно, что периодов ожидания много. А что будет если во время ожидания мы будем выполнять полезную работу?

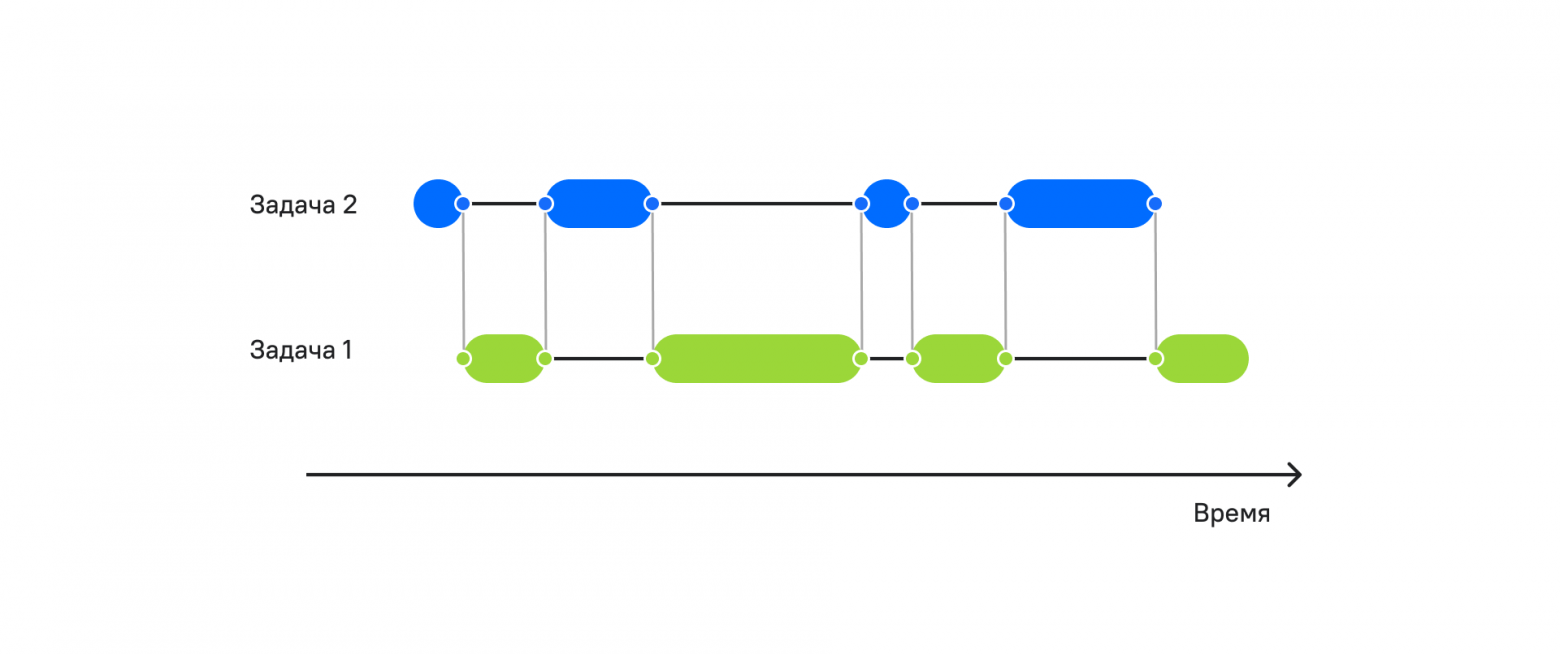

Как видно на рисунке, в моменты ожидания мы выполняем уже две задачи за то же самое время. Чем быстрее мы выполняем работу и чем дольше мы ожидаем, тем больше задач мы можем сделать за одно и то же время.

Для реализации такого поведения асинхронности есть несколько подходов:

-

Реализация на основе коллбэков.

-

Реализация на основе корутин.

Оба подхода имеют место. Например, мощный фреймворк TORNADO реализован именно на основе коллбэков.

У этого подхода есть ряд недостатков:

-

Код перестает выглядеть как синхронный, что усложняет отладку.

-

Ад коллбэков, в котором будет сложно разобраться. Просто погуглите фразу “callback hell”.

Если после этих минусов желание попробовать ещё осталось, то можно в подходе легко разобраться.

А вот подход на основе корутин мы разберем более глубоко. У него также есть ряд преимуществ и недостатков:

Плюсы:

-

Асинхронный код выглядит как синхронный.

-

Нет проблем с общей памятью, и избавляемся от синхронизаций.

-

Не нужно переключать контекст между задачами, что экономит ресурсы нашего компьютера.

-

Теперь нам не нужны коллбэки, но их также можно использовать.

Минусы:

-

Чуть более сложный подход для понимания.

В Python есть ряд библиотек, которые позволяют работать с асинхронностью:

-

asyncio — основная библиотека для работы с асинхронным программированием,

-

aiohttp — для асинхронной работы с запросами,

-

aiofiles — для работы с файловой системой.

Как вы наверное заметили, у библиотек есть префикс aio (asynchronous input output, асинхронный ввод-вывод). Тут как раз решается проблема ожидания. Такие задачи называют IO bound.

Рассмотрим термины, которые нам помогут во всём разобраться.

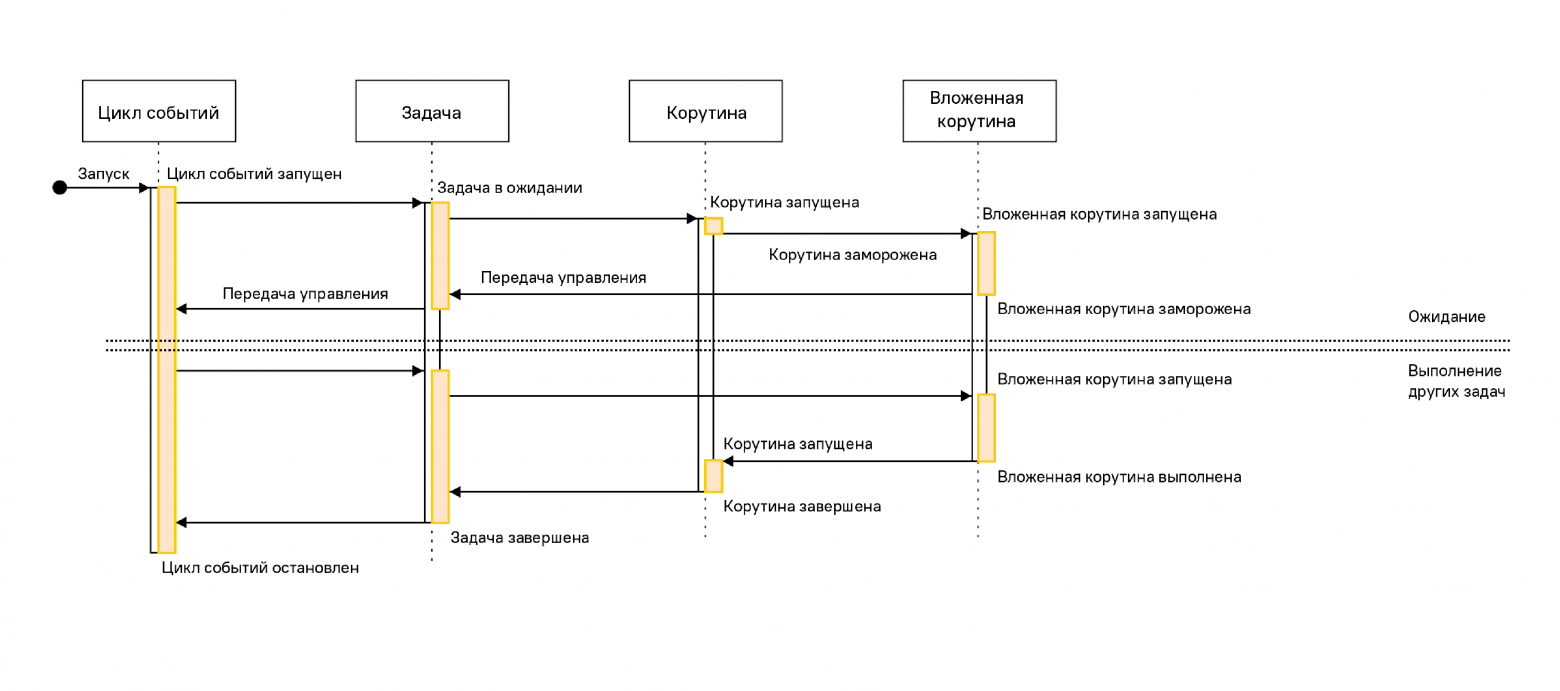

Event loop (цикл событий) — ядро каждого приложения asyncio. Циклы событий запускают асинхронные задачи и обратные вызовы, выполняют операции сетевого ввода-вывода и запускают подпроцессы. Официальную документацию можно прочесть тут.

Корутины — это специальные функции, которые запускаются, используя цикл событий. У них есть особенность — они говорят, когда они будут ждать и передают управление обратно, чтобы другая задача могла выполняться во время ожидания.

Футуры — это определение обычно воспринимается тяжелее всего, но я постараюсь объяснить как можно проще. Это объект, в котором хранится результат и состояние задачи:

+ ожидание (pending)

+ выполнение (running)

+ выполнено (done)

+ отменено (cancelled)

То есть в процессе работы мы можем управлять задачами в зависимости от футуры (статус/результат) задачи.

Корутины могут быть реализованы с использованием генераторов или async/await. Мы выбираем второй вариант как более лаконичный.

Посмотрим, как это выглядит в коде.

Создадим первую корутину:

```

import asyncio

async def hello():

print('Запуск функции hello')

await asyncio.sleep(5) # Отдаем управление обратно в Event loop пока ждем

print('Переключение контекста в функцию hello')

```Теперь у нас есть асинхронная функция. Научимся теперь её запускать. Первое, что хочется сделать — вызвать её как обычную функцию. Давайте попробуем:

```

import asyncio

async def hello():

print('Запуск функции hello')

await asyncio.sleep(5) # Отдаем управление обратно в Event loop пока ждём

print('Переключение контекста в функцию hello')

hello()

```При выполнении ничего не произошло. А вот наш друг интерпретатор выдал предупреждение.

```

RuntimeWarning: coroutine 'hello' was never awaited

hello()

RuntimeWarning: Enable tracemalloc to get the object allocation traceback

```Тут из сообщения становится понятно, что при вызове таким образом асинхронной функции она превращается в асинхронную корутину.

Как же можно запустить корутину?

-

Из другой корутины.

-

Обернуть в задачу.

-

Запустить через метод asyncio.run и run_until_complete из цикла событий.

```

import asyncio

async def hello():

print('Запуск функции hello')

await asyncio.sleep(5) # Отдаем управление обратно в Event loop пока ждём

print('Переключение контекста в функцию hello')

asyncio.run(hello())

```И получили результат, который ожидали.

```

Запуск функции hello

Переключение контекста в функцию hello

```Вызов метода asyncio.run(hello()) принимает корутину, которую необходимо выполнить, открывает цикл событий, выполняет корутину и закрывает цикл событий.

Что делать, если необходимо запустить две задачи конкурентно?

Это поможет нам сделать asyncio.gather, но раз функция asyncio.run принимает только одну корутину, создадим новую корутину, которая будет запускать конкурентно несколько задач.

```

import asyncio

async def hello():

print('Запуск функции hello')

await asyncio.sleep(5) # Отдаем управление обратно в Event loop пока ждём

print('Переключение контекста в функцию hello')

async def starter():

await asyncio.gather(hello(), hello())

asyncio.run(starter())

```И получаем тот результат, который ожидали.

```

Запуск функции hello

Запуск функции hello

Переключение контекста в функцию hello

Переключение контекста в функцию hello

```Время выполнения около 5 секунд. Если бы две функции выполнялись синхронно, то время выполнения составило около 10 секунд.

А если нам необходимо выполнить 10 тысяч раз, сколько времени это займёт? Видоизменяем код:

```

import asyncio

import time

start = time.time() ## точка отсчета времени

async def hello():

print('Запуск функции hello')

await asyncio.sleep(5) # Отдаем управление обратно в Event loop пока ждём

print('Переключение контекста в функцию hello')

async def starter():

await asyncio.gather(*[hello() for i in range(10000)])

asyncio.run(starter())

end = time.time() - start

print(end)

```Получаем результат. Посмотрим на вывод последних нескольких строк, которые нам говорят, сколько минут выполнялся код.

```

…

Переключение контекста в функцию hello

Переключение контекста в функцию hello

Переключение контекста в функцию hello

5.27926778793335

```Неплохо. Чуть больше тех же самых 5 секунд.

Что же это значит? Представьте, что запрос на сторонний сайт занимает порядка 5 секунд. И нам необходимо получить результат тех же самых 10000 запросов. Используя асинхронное программирование, 10 тысяч запросов сеть будут выполняться чуть больше 5 секунд. Правда, здорово?

Но мы пойдем дальше и будем уже более гибко и детально работать с асинхронным выполнением:

```

import asyncio

async def hello():

print('Запуск функции hello')

await asyncio.sleep(5) # Отдаем управление обратно в Event loop пока ждём

print('Переключение контекста в функцию hello')

async def bye():

print('Запуск функции bye')

await asyncio.sleep(5) # Отдаем управление обратно в Event loop пока ждём

print('Переключение контекста в функцию byе')

ioloop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

tasks = [ioloop.create_task(hello()), ioloop.create_task(bye())]

tasks_for_wait = asyncio.wait(tasks)

ioloop.run_until_complete(tasks_for_wait)

ioloop.close()

```В этом примере мы более гибко управляем циклом событий. Сначала получаем/создаем основной цикл событий. Затем создаем задачи и объединяем их запускаем на выполнение, пока не завершится. Затем уже закрываем цикл событий. Нужно помнить, что порядок выполнения задач при конкурентном выполнении мы не можем гарантировать, и необходимо разрабатывать приложения с учетом этой особенности.

Теперь давайте попробуем управлять выполнениями задач и рассмотрим код ниже:

```

import asyncio

async def hello():

print('Запуск функции hello')

await asyncio.sleep(5) # Отдаем управление обратно в Event loop пока ждём

print('Переключение контекста в функцию hello')

return 'Выполнена функция hello'

async def bye():

print('Запуск функции bye')

await asyncio.sleep(2) # Отдаем управление обратно в Event loop пока ждём

print('Переключение контекста в функцию byе')

return 'Выполнена функция bye'

async def starter(ioloop):

tasks = [ioloop.create_task(hello()), ioloop.create_task(bye())]

done, pending = await asyncio.wait(tasks, return_when=asyncio.FIRST_COMPLETED)

result = done.pop().result()

for pending_future in pending:

pending_future.cancel()

print(result)

ioloop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

ioloop.run_until_complete(starter(ioloop))

ioloop.close()

```Результат будет таким:

```

Запуск функции hello

Запуск функции bye

Переключение контекста в функцию byе

Выполнена функция bye

```Теперь только представьте, какие возможности у нас открылись! Например, мы можем запрашивать курсы валют сразу с нескольких ресурсов, и принимать результат того, который быстрее ответит. Чувствуете, как растет скорость и устойчивость приложения?

Или ещё такой пример. Мы можем динамически добавлять новые задачи, когда одна из задач выполнена. Например, парсить сайт в 20 задач. Только в этом случае добавляем к футурам в статусе pending новую задачу.

А самое приятное — наши асинхронные задачи выглядят как синхронные:

-

Работая в один поток, можно делать больше работы;

-

Удобная отладка;

-

Нет проблем с блокировками;

-

Можем использовать обратные вызовы (коллбэки) и отложенные обратные вызовы вдобавок к нашему асинхронному коду. Для этого посмотрите на методы цикла событий call_soon, call_later, call_at.

Для работы с конкурентностью есть различные библиотеки, которые решают самые востребованные задачи IO:

-

aiohttp — работа с HTTP запросами;

-

aiofiles — работа с файлами.

Мы рассмотрели темы асинхронного и параллельного программирования. Теперь осталось дело за малым, опробовать всё это на практике.

Итого

Отдельные процессы

Плюсы:

+ Работают параллельно.

+ Используют все ресурсы ядра процессора.

+ Можно загрузить все ядра процессора.

+ Изолированная память.

+ Независимые системные процессы.

+ Подходит для CPU bound операций.

Минусы:

-

Если необходимо использовать общую память, то необходимо синхронизировать, так как нет общих переменных.

-

Требуют больших ресурсов, так как запускают отдельный интерпретатор.

Используем там, где обрабатываемые данные не зависят от других процессов и данных. Например:

+ Расчет нейронных сетей.

+ Обработка изолированных фотографий.

+ Архивирование изолированных файлов.

+ Конвертация форматов файлов.

Отдельные потоки

Плюсы:

+ Работают параллельно.

+ Используют немного памяти.

+ Общая память.

Минусы:

-

Одновременный доступ к памяти может приводить к конфликтам.

-

Сложный код.

Используем там, где код много раз ожидает, пока выполнится задача. Например:

+ Работа с сетью.

Асинхронность

Плюсы:

+ Работает в одном процессе и в одном потоке.

+ Экономное использование памяти.

+ Подходит для I/O bound операций.

+ Работает конкурентно.

Минусы:

-

Сложность отладки.

-

CPU bound операции блокируют все задачи.

Используем там, где код много раз ожидает. Например:

+ Работа с сетью.

+ Работа с файловой системой.

Основываясь на конкретных плюсах и минусах, нам становится легче выбирать подход и грамотно использовать процессорное время и память. Хотя Python является мультипарадигменным языком общего назначения, на нем можно писать практически любые программы, используя любой подход. Но особенно приятно, когда ваш веб-сервис может держать в сотню раз больше соединений или отрабатывать запросы в 8 раз быстрее, обходясь меньшим количеством памяти.

Спасибо за внимание! Надеемся, что этот материал был полезен для вас.

Авторские материалы для разработчиков мы также публикуем в наших соцсетях – ВК и Telegram.

Introduction

Interacting with Windows shell to end process is very common,

there are many ways to do so, like through the traditional batch script

but to gain more flexibility, using python is probably a better idea.

os.systemis not the most elegant way to use, and it is meant to be replaced bysubprocesssubprocesscomes with Python standard library and allows us to spawn new processes, connect to their input/output/error pipes, and obtain their return codespsutil(python system and process utilities) is a cross-platform library for retrieving information on running processes and system utilization.

However, it is a third-party library

Bare Minimum

the bare minimum command to kill process utilizes window’s taskkill;

which doesn’t matter if we use os.system or subprocess

1 |

import os |

Using os.system

Now consider a more flexible case where we want to gather information about the processes like its PID,

and then proceed on ending the process. One of the downside of window shell command is that the output

can’t be passed on to other command, the output is just text. Therefore, we

output the text to a csv file which we will later process.

1 |

import csv |

Using subprocess

With subprocess, we no longer need to create a temp file to store the output.

Using psutil

1 |

import psutil |

we can find process start time by using

1 |

import time |

to kill process, either kill() or terminate() will work

respectfully, SIGKILL or SIGTERM

1 |

p = psutil.Process(PID) |

Bonus: Find Open Port (for socket connection)

1 |

process = psutil.Process(pid=PID) |

Bonus: Find Main Window Title

ctypes is a foreign function library for python, resulting a not-pythonic function

Reference

Microsoft Doc — tasklist

ThisPointer — Python : Check if a process is running by name and find it’s Process ID (PID)

Johannes Sasongko — Win32 Python: Getting all window titles

Stack Overflow — Obtain Active window using Python

Microsoft Docs — winuser.h header

Execute a child program in a new process. On POSIX, the class uses

os.execvp()-like behavior to execute the child program. On Windows,

the class uses the Windows CreateProcess() function. The arguments to

Popen are as follows.

args should be a sequence of program arguments or else a single string.

By default, the program to execute is the first item in args if args is

a sequence. If args is a string, the interpretation is

platform-dependent and described below. See the shell and executable

arguments for additional differences from the default behavior. Unless

otherwise stated, it is recommended to pass args as a sequence.

On POSIX, if args is a string, the string is interpreted as the name or

path of the program to execute. However, this can only be done if not

passing arguments to the program.

Note

shlex.split() can be useful when determining the correct

tokenization for args, especially in complex cases:

>>> import shlex, subprocess >>> command_line = input() /bin/vikings -input eggs.txt -output "spam spam.txt" -cmd "echo '$MONEY'" >>> args = shlex.split(command_line) >>> print(args) ['/bin/vikings', '-input', 'eggs.txt', '-output', 'spam spam.txt', '-cmd', "echo '$MONEY'"] >>> p = subprocess.Popen(args) # Success!

Note in particular that options (such as -input) and arguments (such

as eggs.txt) that are separated by whitespace in the shell go in separate

list elements, while arguments that need quoting or backslash escaping when

used in the shell (such as filenames containing spaces or the echo command

shown above) are single list elements.

On Windows, if args is a sequence, it will be converted to a string in a

manner described in Converting an argument sequence to a string on Windows. This is because

the underlying CreateProcess() operates on strings.

The shell argument (which defaults to False) specifies whether to use

the shell as the program to execute. If shell is True, it is

recommended to pass args as a string rather than as a sequence.

On POSIX with shell=True, the shell defaults to /bin/sh. If

args is a string, the string specifies the command

to execute through the shell. This means that the string must be

formatted exactly as it would be when typed at the shell prompt. This

includes, for example, quoting or backslash escaping filenames with spaces in

them. If args is a sequence, the first item specifies the command string, and

any additional items will be treated as additional arguments to the shell

itself. That is to say, Popen does the equivalent of:

Popen(['/bin/sh', '-c', args[0], args[1], ...])

On Windows with shell=True, the COMSPEC environment variable

specifies the default shell. The only time you need to specify

shell=True on Windows is when the command you wish to execute is built

into the shell (e.g. dir or copy). You do not need

shell=True to run a batch file or console-based executable.

Note

Read the Security Considerations section before using shell=True.

bufsize will be supplied as the corresponding argument to the

open() function when creating the stdin/stdout/stderr pipe

file objects:

0means unbuffered (read and write are one

system call and can return short)1means line buffered

(only usable ifuniversal_newlines=Truei.e., in a text mode)- any other positive value means use a buffer of approximately that

size - negative bufsize (the default) means the system default of

io.DEFAULT_BUFFER_SIZE will be used.

Changed in version 3.3.1: bufsize now defaults to -1 to enable buffering by default to match the

behavior that most code expects. In versions prior to Python 3.2.4 and

3.3.1 it incorrectly defaulted to 0 which was unbuffered

and allowed short reads. This was unintentional and did not match the

behavior of Python 2 as most code expected.

The executable argument specifies a replacement program to execute. It

is very seldom needed. When shell=False, executable replaces the

program to execute specified by args. However, the original args is

still passed to the program. Most programs treat the program specified

by args as the command name, which can then be different from the program

actually executed. On POSIX, the args name

becomes the display name for the executable in utilities such as

ps. If shell=True, on POSIX the executable argument

specifies a replacement shell for the default /bin/sh.

stdin, stdout and stderr specify the executed program’s standard input,

standard output and standard error file handles, respectively. Valid values

are PIPE, DEVNULL, an existing file descriptor (a positive

integer), an existing file object, and None. PIPE

indicates that a new pipe to the child should be created. DEVNULL

indicates that the special file os.devnull will be used. With the

default settings of None, no redirection will occur; the child’s file

handles will be inherited from the parent. Additionally, stderr can be

STDOUT, which indicates that the stderr data from the applications

should be captured into the same file handle as for stdout.

If preexec_fn is set to a callable object, this object will be called in the

child process just before the child is executed.

(POSIX only)

Warning

The preexec_fn parameter is not safe to use in the presence of threads

in your application. The child process could deadlock before exec is

called.

If you must use it, keep it trivial! Minimize the number of libraries

you call into.

Note

If you need to modify the environment for the child use the env

parameter rather than doing it in a preexec_fn.

The start_new_session parameter can take the place of a previously

common use of preexec_fn to call os.setsid() in the child.

If close_fds is true, all file descriptors except 0, 1 and

2 will be closed before the child process is executed. (POSIX only).

The default varies by platform: Always true on POSIX. On Windows it is

true when stdin/stdout/stderr are None, false otherwise.

On Windows, if close_fds is true then no handles will be inherited by the

child process. Note that on Windows, you cannot set close_fds to true and

also redirect the standard handles by setting stdin, stdout or stderr.

Changed in version 3.2: The default for close_fds was changed from False to

what is described above.

pass_fds is an optional sequence of file descriptors to keep open

between the parent and child. Providing any pass_fds forces

close_fds to be True. (POSIX only)

New in version 3.2: The pass_fds parameter was added.

If cwd is not None, the function changes the working directory to

cwd before executing the child. cwd can be a str and

path-like object. In particular, the function

looks for executable (or for the first item in args) relative to cwd

if the executable path is a relative path.

Changed in version 3.6: cwd parameter accepts a path-like object.

If restore_signals is true (the default) all signals that Python has set to

SIG_IGN are restored to SIG_DFL in the child process before the exec.

Currently this includes the SIGPIPE, SIGXFZ and SIGXFSZ signals.

(POSIX only)

Changed in version 3.2: restore_signals was added.

If start_new_session is true the setsid() system call will be made in the

child process prior to the execution of the subprocess. (POSIX only)

Changed in version 3.2: start_new_session was added.

If env is not None, it must be a mapping that defines the environment

variables for the new process; these are used instead of the default

behavior of inheriting the current process’ environment.

Note

If specified, env must provide any variables required for the program to

execute. On Windows, in order to run a side-by-side assembly the

specified env must include a valid SystemRoot.

If encoding or errors are specified, the file objects stdin, stdout

and stderr are opened in text mode with the specified encoding and

errors, as described above in Frequently Used Arguments. If

universal_newlines is True, they are opened in text mode with default

encoding. Otherwise, they are opened as binary streams.

New in version 3.6: encoding and errors were added.

If given, startupinfo will be a STARTUPINFO object, which is

passed to the underlying CreateProcess function.

creationflags, if given, can be CREATE_NEW_CONSOLE or

CREATE_NEW_PROCESS_GROUP. (Windows only)

Popen objects are supported as context managers via the with statement:

on exit, standard file descriptors are closed, and the process is waited for.

with Popen(["ifconfig"], stdout=PIPE) as proc: log.write(proc.stdout.read())

Changed in version 3.2: Added context manager support.

Changed in version 3.6: Popen destructor now emits a ResourceWarning warning if the child

process is still running.

В скриптах, написанных для автоматизации определенных задач, нам часто требуется запускать внешние программы и контролировать их выполнение. При работе с Python мы можем использовать модуль subprocess для создания подобных скриптов. Этот модуль является частью стандартной библиотеки языка. В данном руководстве мы кратко рассмотрим subprocess и изучим основы его использования.

Прочитав статью, вы узнаете как:

- Использовать функцию

runдля запуска внешнего процесса. - Получить стандартный вывод процесса и информацию об ошибках.

- Проверить код возврата процесса и вызвать исключение в случае сбоя.

- Запустить процесс, используя оболочку в качестве посредника.

- Установить время ожидания завершения процесса.

- Использовать класс

Popenнапрямую для создания конвейера (pipe) между двумя процессами.

Так как модуль subprocess почти всегда используют с Linux все примеры будут касаться Ubuntu. Для пользователей Windows советую скачать терминал Ubuntu 18.04 LTS.

Функция «run»

Функция run была добавлена в модуль subprocess только в относительно последних версиях Python (3.5). Теперь ее использование является рекомендуемым способом создания процессов и должно решать наиболее распространенные задачи. Прежде всего, давайте посмотрим на простейший случай применения функции run.

Предположим, мы хотим запустить команду ls -al; для этого в оболочке Python нам нужно ввести следующие инструкции:

>>> import subprocess

>>> process = subprocess.run(['ls', '-l', '-a'])

Вывод внешней команды ls отображается на экране:

total 12

drwxr-xr-x 1 cnc cnc 4096 Apr 27 16:21 .

drwxr-xr-x 1 root root 4096 Apr 27 15:40 ..

-rw------- 1 cnc cnc 2445 May 6 17:43 .bash_history

-rw-r--r-- 1 cnc cnc 220 Apr 27 15:40 .bash_logout

-rw-r--r-- 1 cnc cnc 3771 Apr 27 15:40 .bashrcЗдесь мы просто использовали первый обязательный аргумент функции run, который может быть последовательностью, «описывающей» команду и ее аргументы (как в примере), или строкой, которая должна использоваться при запуске с аргументом shell=True (мы рассмотрим последний случай позже).

Захват вывода команды: stdout и stderr

Что, если мы не хотим, чтобы вывод процесса отображался на экране. Вместо этого, нужно чтобы он сохранялся: на него можно было ссылаться после выхода из процесса? В этом случае нам стоит установить для аргумента функции capture_output значение True:

>>> process = subprocess.run(['ls', '-l', '-a'], capture_output=True)

Как мы можем впоследствии получить вывод (stdout и stderr) процесса? Если вы посмотрите на приведенные выше примеры, то увидите, что мы использовали переменную process для ссылки на объект CompletedProcess, возвращаемый функцией run. Этот объект представляет процесс, запущенный функцией, и имеет много полезных свойств. Помимо прочих, stdout и stderr используются для «хранения» соответствующих дескрипторов команды, если, как уже было сказано, для аргумента capture_output установлено значение True. В этом случае, чтобы получить stdout, мы должны использовать:

>>> process = subprocess.run(['ls', '-l', '-a'], capture_output=True)

>>> process.stdout

b'total 12\ndrwxr-xr-x 1 cnc cnc 4096 Apr 27 16:21 .\ndrwxr-xr-x 1 root root 4096 Apr 27 15:40 ..\n-rw------- 1 cnc cnc 2445 May 6 17:43 .bash_history\n-rw-r--r-- 1 cnc cnc 220 Apr 27 15:40 .bash_logout...По умолчанию stdout и stderr представляют собой последовательности байтов. Если мы хотим, чтобы они хранились в виде строк, мы должны установить для аргумента text функции run значение True.

Управление сбоями процесса

Команда, которую мы запускали в предыдущих примерах, была выполнена без ошибок. Однако при написании программы следует принимать во внимание все случаи. Так, что случится, если порожденный процесс даст сбой? По умолчанию ничего «особенного» не происходит. Давайте посмотрим на примере: мы снова запускаем команду ls, пытаясь вывести список содержимого каталога /root, который не доступен для чтения обычным пользователям:

>>> process = subprocess.run(['ls', '-l', '-a', '/root'])

Мы можем узнать, не завершился ли запущенный процесс ошибкой, проверив его код возврата, который хранится в свойстве returncode объекта CompletedProcess:

Видите? В этом случае returncode равен 2, подтверждая, что процесс столкнулся с ошибкой, связанной с недостаточными правами доступа, и не был успешно завершен. Мы могли бы проверять выходные данные процесса таким образом чтобы при возникновении сбоя возникало исключение. Используйте аргумент check функции run: если для него установлено значение True, то в случае, когда внешний процесс завершается ошибкой, возникает исключение CalledProcessError:

>>> process = subprocess.run(['ls', '-l', '-a', '/root'])

ls: cannot open directory '/root': Permission deniedОбработка исключений в Python довольно проста. Поэтому для управления сбоями процесса мы могли бы написать что-то вроде:

>>> try:

... process = subprocess.run(['ls', '-l', '-a', '/root'], check=True)

... except subprocess.CalledProcessError as e:

... print(f"Ошибка команды {e.cmd}!")

...

ls: cannot open directory '/root': Permission denied

['ls', '-l', '-a', '/root'] failed!

>>>Исключение CalledProcessError, как мы уже сказали, возникает, когда код возврата процесса не является 0. У данного объекта есть такие свойства, как returncode, cmd, stdout, stderr; то, что они представляют, довольно очевидно. Например, в приведенном выше примере мы просто использовали свойство cmd, чтобы отобразить последовательность, которая использовалась для запуска команды при возникновении исключения.

Выполнение процесса в оболочке

Процессы, запущенные с помощью функции run, выполняются «напрямую», это означает, что для их запуска не используется оболочка: поэтому для процесса не доступны никакие переменные среды и не выполняются раскрытие и подстановка выражений. Давайте посмотрим на пример, который включает использование переменной $HOME:

>>> process = subprocess.run(['ls', '-al', '$HOME'])

ls: cannot access '$HOME': No such file or directoryКак видите, переменная $HOME не была заменена на соответствующее значение. Такой способ выполнения процессов является рекомендованным, так как позволяет избежать потенциальные угрозы безопасности. Однако, в некоторых случаях, когда нам нужно вызвать оболочку в качестве промежуточного процесса, достаточно установить для параметра shell функции run значение True. В таких случаях желательно указать команду и ее аргументы в виде строки:

>>> process = subprocess.run('ls -al $HOME', shell=True)

total 12

drwxr-xr-x 1 cnc cnc 4096 Apr 27 16:21 .

drwxr-xr-x 1 root root 4096 Apr 27 15:40 ..

-rw------- 1 cnc cnc 2445 May 6 17:43 .bash_history

-rw-r--r-- 1 cnc cnc 220 Apr 27 15:40 .bash_logout

...Все переменные, существующие в пользовательской среде, могут использоваться при вызове оболочки в качестве промежуточного процесса. Хотя это может показаться удобным, такой подход является источником проблем. Особенно при работе с потенциально опасным вводом, который может привести к внедрению вредоносного shell-кода. Поэтому запуск процесса с shell=True не рекомендуется и должен использоваться только в безопасных случаях.

Ограничение времени работы процесса

Обычно мы не хотим, чтобы некорректно работающие процессы бесконечно исполнялись в нашей системе после их запуска. Если мы используем параметр timeout функции run, то можем указать количество времени в секундах, в течение которого процесс должен завершиться. Если он не будет завершен за это время, процесс будет остановлен сигналом SIGKILL. Который, как мы знаем, не может быть перехвачен. Давайте продемонстрируем это, запустив длительный процесс и предоставив timeout в секундах:

>>> process = subprocess.run(['ping', 'google.com'], timeout=5)

PING google.com (216.58.208.206) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from par10s21-in-f206.1e100.net (216.58.208.206): icmp_seq=1 ttl=118 time=15.8 ms

64 bytes from par10s21-in-f206.1e100.net (216.58.208.206): icmp_seq=2 ttl=118 time=15.7 ms

64 bytes from par10s21-in-f206.1e100.net (216.58.208.206): icmp_seq=3 ttl=118 time=19.3 ms

64 bytes from par10s21-in-f206.1e100.net (216.58.208.206): icmp_seq=4 ttl=118 time=15.6 ms

64 bytes from par10s21-in-f206.1e100.net (216.58.208.206): icmp_seq=5 ttl=118 time=17.0 ms

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "/usr/lib/python3.8/subprocess.py", line 495, in run

stdout, stderr = process.communicate(input, timeout=timeout)

File "/usr/lib/python3.8/subprocess.py", line 1028, in communicate

stdout, stderr = self._communicate(input, endtime, timeout)

File "/usr/lib/python3.8/subprocess.py", line 1894, in _communicate

self.wait(timeout=self._remaining_time(endtime))

File "/usr/lib/python3.8/subprocess.py", line 1083, in wait

return self._wait(timeout=timeout)

File "/usr/lib/python3.8/subprocess.py", line 1798, in _wait

raise TimeoutExpired(self.args, timeout)

subprocess.TimeoutExpired: Command '['ping', 'google.com']' timed out after 4.999637200000052 seconds

В приведенном выше примере мы запустили команду ping без указания фиксированного числа пакетов ECHO REQUEST, поэтому она потенциально может работать вечно. Мы также установили время ожидания в 5 секунд с помощью параметра timeout. Как мы видим, ping была запущена, а по истечении 5 секунд возникло исключение TimeoutExpired и процесс был остановлен.

Функции call, check_output и check_call

Как мы уже говорили ранее, функция run является рекомендуемым способом запуска внешнего процесса. Она должна использоваться в большинстве случаев. До того, как она была представлена в Python 3.5, тремя основными функциями API высокого уровня, применяемыми для создания процессов, были call, check_output и check_call; давайте взглянем на них вкратце.

Прежде всего, функция call: она используется для выполнения команды, описанной параметром args; она ожидает завершения команды; ее результатом является соответствующий код возврата. Это примерно соответствует базовому использованию функции run.

Поведение функции check_call практически не отличается от run, когда для параметра check задано значение True: она запускает указанную команду и ожидает ее завершения. Если код возврата не равен 0, возникает исключение CalledProcessError.

Наконец, функция check_output. Она работает аналогично check_call, но возвращает вывод запущенной программы, то есть он не отображается при выполнении функции.

Работа на более низком уровне с классом Popen

До сих пор мы изучали функции API высокого уровня в модуле subprocess, особенно run. Все они под капотом используют класс Popen. Из-за этого в подавляющем большинстве случаев нам не нужно взаимодействовать с ним напрямую. Однако, когда требуется большая гибкость, без создания объектов Popen не обойтись.

Предположим, например, что мы хотим соединить два процесса, воссоздав поведение конвейера (pipe) оболочки. Как мы знаем, когда передаем две команды в оболочку, стандартный вывод той, что находится слева от пайпа «|», используется как стандартный ввод той, которая находится справа. В приведенном ниже примере результат выполнения двух связанных конвейером команд сохраняется в переменной:

$ output="$(dmesg | grep sda)"Чтобы воссоздать подобное поведение с помощью модуля subprocess без установки параметра shell в значение True, как мы видели ранее, мы должны напрямую использовать класс Popen:

dmesg = subprocess.Popen(['dmesg'], stdout=subprocess.PIPE)

grep = subprocess.Popen(['grep', 'sda'], stdin=dmesg.stdout)

dmesg.stdout.close()

output = grep.comunicate()[0]

Рассматривая данный пример, вы должны помнить, что процесс, запущенный с использованием класса Popen, не блокирует выполнение скрипта.

Первое, что мы сделали в приведенном выше фрагменте кода, — это создали объект Popen, представляющий процесс dmesg. Мы установили stdout этого процесса на subprocess.PIPE. Данное значение указывает, что пайп к указанному потоку должен быть открыт.

Затем мы создали еще один экземпляр класса Popen для процесса grep. В конструкторе Popen мы, конечно, указали команду и ее аргументы, но вот что важно, мы установили стандартный вывод процесса dmesg в качестве стандартного ввода для grep (stdin=dmesg.stdout), чтобы воссоздать поведение конвейера оболочки.

После создания объекта Popen для команды grep мы закрыли поток stdout процесса dmesg, используя метод close(). Это, как указано в документации, необходимо для того, чтобы первый процесс мог получить сигнал SIGPIPE. Дело в том, что обычно, когда два процесса соединены конвейером, если один справа от «|» (grep в нашем примере) завершается раньше, чем тот, что слева (dmesg), то последний получает сигнал SIGPIPE (пайп закрыт) и по умолчанию тоже заканчивает свою работу.

Однако при репликации пайплайна между двумя командами в Python возникает проблема. stdout первого процесса открывается как в родительском скрипте, так и в стандартном вводе другого процесса. Таким образом, даже если процесс grep завершится, пайп останется открытым в вызывающем процессе (нашем скрипте), поэтому dmesg никогда не получит сигнал SIGPIPE. Вот почему нам нужно закрыть поток stdout первого процесса в нашем основном скрипте после запуска второго.

Последнее, что мы сделали, — это вызвали метод communicate() объекта grep. Этот метод можно использовать для необязательной передачи данных в stdin процесса. Он ожидает завершения процесса и возвращает кортеж. Где первый элемент — это stdout (на который ссылается переменная output), а второй — stderr процесса.

Заключение

В этом руководстве мы увидели рекомендуемый способ создания внешних процессов в Python с помощью модуля subprocess и функции run. Использование этой функции должно быть достаточным для большинства случаев. Однако, когда требуется более высокий уровень гибкости, следует использовать класс Popen напрямую.

Как всегда, мы советуем вам взглянуть на документацию subprocess, чтобы получить полную информацию о функциях и классах, доступных в данном модуле.

If you’ve ever wanted to simplify your command-line scripting or use Python alongside command-line applications—or any applications for that matter—then the Python subprocess module can help. From running shell commands and command-line applications to launching GUI applications, the Python subprocess module can help.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll be able to:

- Understand how the Python

subprocessmodule interacts with the operating system - Issue shell commands like

lsordir - Feed input into a process and use its output.

- Handle errors when using

subprocess - Understand the use cases for

subprocessby considering practical examples

In this tutorial, you’ll get a high-level mental model for understanding processes, subprocesses, and Python before getting stuck into the subprocess module and experimenting with an example. After that, you’ll start exploring the shell and learn how you can leverage Python’s subprocess with Windows and UNIX-based shells and systems. Specifically, you’ll cover communication with processes, pipes and error handling.

Once you have the basics down, you’ll be exploring some practical ideas for how to leverage Python’s subprocess. You’ll also dip your toes into advanced usage of Python’s subprocess by experimenting with the underlying Popen() constructor.

Processes and Subprocesses

First off, you might be wondering why there’s a sub in the Python subprocess module name. And what exactly is a process, anyway? In this section, you’ll answer these questions. You’ll come away with a high-level mental model for thinking about processes. If you’re already familiar with processes, then you might want to skip directly to basic usage of the Python subprocess module.

Processes and the Operating System

Whenever you use a computer, you’ll always be interacting with programs. A process is the operating system’s abstraction of a running program. So, using a computer always involve processes. Start menus, app bars, command-line interpreters, text editors, browsers, and more—every application comprises one or more processes.

A typical operating system will report hundreds or even thousands of running processes, which you’ll get to explore shortly. However, central processing units (CPUs) typically only have a handful of cores, which means that they can only run a handful of instructions simultaneously. So, you may wonder how thousands of processes can appear to run at the same time.

In short, the operating system is a marvelous multitasker—as it has to be. The CPU is the brain of a computer, but it operates at the nanosecond timescale. Most other components of a computer are far slower than the CPU. For instance, a magnetic hard disk read takes thousands of times longer than a typical CPU operation.

If a process needs to write something to the hard drive, or wait for a response from a remote server, then the CPU would sit idle most of the time. Multitasking keeps the CPU busy.

Part of what makes the operating system so great at multitasking is that it’s fantastically organized too. The operating system keeps track of processes in a process table or process control block. In this table, you’ll find the process’s file handles, security context, references to its address spaces, and more.

The process table allows the operating system to abandon a particular process at will, because it has all the information it needs to come back and continue with the process at a later time. A process may be interrupted many thousands of times during execution, but the operating system always finds the exact point where it left off upon returning.

An operating system doesn’t boot up with thousands of processes, though. Many of the processes you’re familiar with are started by you. In the next section, you’ll look into the lifetime of a process.

Process Lifetime

Think of how you might start a Python application from the command line. This is an instance of your command-line process starting a Python process:

The process that starts another process is referred to as the parent, and the new process is referred to as the child. The parent and child processes run mostly independently. Sometimes the child inherits specific resources or contexts from the parent.

As you learned in Processes and the Operating System, information about processes is kept in a table. Each process keeps track of its parents, which allows the process hierarchy to be represented as a tree. You’ll be exploring your system’s process tree in the next section.

The parent-child relationship between a process and its subprocess isn’t always the same. Sometimes the two processes will share specific resources, like inputs and outputs, but sometimes they won’t. Sometimes child processes live longer than the parent. A child outliving the parent can lead to orphaned or zombie processes, though more discussion about those is outside the scope of this tutorial.

When a process has finished running, it’ll usually end. Every process, on exit, should return an integer. This integer is referred to as the return code or exit status. Zero is synonymous with success, while any other value is considered a failure. Different integers can be used to indicate the reason why a process has failed.

In the same way that you can return a value from a function in Python, the operating system expects an integer return value from a process once it exits. This is why the canonical C main() function usually returns an integer:

// minimal_program.c

int main(){

return 0;

}

This example shows a minimal amount of C code necessary for the file to compile with gcc without any warnings. It has a main() function that returns an integer. When this program runs, the operating system will interpret its execution as successful since it returns zero.

So, what processes are running on your system right now? In the next section, you’ll explore some of the tools that you can use to take a peek at your system’s process tree. Being able to see what processes are running and how they’re structured will come in handy when visualizing how the subprocess module works.

Active Processes on Your System

You may be curious to see what processes are running on your system right now. To do that, you can use platform-specific utilities to track them:

- Windows

- Linux + macOS

There are many tools available for Windows, but one which is easy to get set up, is fast, and will show you the process tree without much effort is Process Hacker.

You can install Process Hacker by going to the downloads page or with Chocolatey:

PS> choco install processhacker

Open the application, and you should immediately see the process tree.

One of the native commands that you can use with PowerShell is Get-Process, which lists the active processes on the command line. tasklist is a command prompt utility that does the same.

The official Microsoft version of Process Hacker is part of the Sysinternals utilities, namely Process Monitor and Process Explorer. You also get PsList, which is a command-line utility similar to pstree on UNIX. You can install Sysinternals by going to the downloads page or by using Chocolatey:

PS> choco install sysinternals

You can also use the more basic, but classic, Task Manager—accessible by pressing Win+X and selecting the Task Manager.

For UNIX-based systems, there are many command-line utilities to choose from:

top: The classic process and resource monitor, often installed by default. Once it’s running, to see the tree view, also called the forest view, press Shift+V. The forest view may not work on the default macOStop.htop: More advanced and user-friendly version oftop.atop: Another version oftopwith more information, but more technical.bpytop: A Python implementation oftopwith nice visuals.pstree: A utility specifically to explore the process tree.

On macOS, you also have the Activity Monitor application in your utilities. In the View menu, if you select All Processes, Hierarchically, you should be able to see your process tree.

You can also explore the Python psutil library, which allows you to retrieve running process information on both Windows and UNIX-based systems.

One universal attribute of process tracking across systems is that each process has a process identification number, or PID, which is a unique integer to identify the process within the context of the operating system. You’ll see this number on most of the utilities listed above.

Along with the PID, it’s typical to see the resource usage, such as CPU percentage and amount of RAM that a particular process is using. This is the information that you look for if a program is hogging all your resources.

The resource utilization of processes can be useful for developing or debugging scripts that use the subprocess module, even though you don’t need the PID, or any information about what resources processes are using in the code itself. While playing with the examples that are coming up, consider leaving a representation of the process tree open to see the new processes pop up.

You now have a bird’s-eye view of processes. You’ll deepen your mental model throughout the tutorial, but now it’s time to see how to start your own processes with the Python subprocess module.

Overview of the Python subprocess Module

The Python subprocess module is for launching child processes. These processes can be anything from GUI applications to the shell. The parent-child relationship of processes is where the sub in the subprocess name comes from. When you use subprocess, Python is the parent that creates a new child process. What that new child process is, is up to you.

Python subprocess was originally proposed and accepted for Python 2.4 as an alternative to using the os module. Some documented changes have happened as late as 3.8. The examples in this article were tested with Python 3.10.4, but you only need 3.8+ to follow along with this tutorial.

Most of your interaction with the Python subprocess module will be via the run() function. This blocking function will start a process and wait until the new process exits before moving on.

The documentation recommends using run() for all cases that it can handle. For edge cases where you need more control, the Popen class can be used. Popen is the underlying class for the whole subprocess module. All functions in the subprocess module are convenience wrappers around the Popen() constructor and its instance methods. Near the end of this tutorial, you’ll dive into the Popen class.

You may come across other functions like call(), check_call(), and check_output(), but these belong to the older subprocess API from Python 3.5 and earlier. Everything these three functions do can be replicated with the newer run() function. The older API is mainly still there for backwards compatibility, and you won’t cover it in this tutorial.

There’s also a fair amount of redundancy in the subprocess module, meaning that there are various ways to achieve the same end goal. You won’t be exploring all variations in this tutorial. What you will find, though, are robust techniques that should keep you on the right path.

Basic Usage of the Python subprocess Module

In this section, you’ll take a look at some of the most basic examples demonstrating the usage of the subprocess module. You’ll start by exploring a bare-bones command-line timer program with the run() function.

If you want to follow along with the examples, then create a new folder. All the examples and programs can be saved in this folder. Navigate to this newly created folder on the command line in preparation for the examples coming up. All the code in this tutorial is standard library Python—with no external dependencies required—so a virtual environment isn’t necessary.

The Timer Example

To come to grips with the Python subprocess module, you’ll want a bare-bones program to run and experiment with. For this, you’ll use a program written in Python:

# timer.py

from argparse import ArgumentParser

from time import sleep

parser = ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("time", type=int)

args = parser.parse_args()

print(f"Starting timer of {args.time} seconds")

for _ in range(args.time):

print(".", end="", flush=True)

sleep(1)

print("Done!")

The timer program uses argparse to accept an integer as an argument. The integer represents the number of seconds that the timer should wait until exiting, which the program uses sleep() to achieve. It’ll play a small animation representing each passing second until it exits:

It’s not much, but the key is that it serves as a cross-platform process that runs for a few seconds and which you can easily tinker with. You’ll be calling it with subprocess as if it were a separate executable.

Okay, ready to get stuck in! Once you have the timer.py program ready, open a Python interactive session and call the timer with subprocess:

>>>

>>> import subprocess

>>> subprocess.run(["python", "timer.py", "5"])

Starting timer of 5 seconds

.....Done!

CompletedProcess(args=['python', 'timer.py', '5'], returncode=0)

With this code, you should’ve seen the animation playing right in the REPL. You imported subprocess and then called the run() function with a list of strings as the one and only argument. This is the args parameter of the run() function.

On executing run(), the timer process starts, and you can see its output in real time. Once it’s done, it returns an instance of the CompletedProcess class.

On the command line, you might be used to starting a program with a single string:

However, with run() you need to pass the command as a sequence, as shown in the run() example. Each item in the sequence represents a token which is used for a system call to start a new process.

Shells typically do their own tokenization, which is why you just write the commands as one long string on the command line. With the Python subprocess module, though, you have to break up the command into tokens manually. For instance, executable names, flags, and arguments will each be one token.

Now that you’re familiar with some of the very basics of starting new processes with the Python subprocess module, coming up you’ll see that you can run any kind of process, not just Python or text-based programs.

The Use of subprocess to Run Any App

With subprocess, you aren’t limited to text-based applications like the shell. You can call any application that you can with the Start menu or app bar, as long as you know the precise name or path of the program that you want to run:

- Windows

- Linux

- macOS

>>>

>>> subprocess.run(["notepad"])

CompletedProcess(args=['notepad'], returncode=0)

>>>

>>> subprocess.run(["gedit"])

CompletedProcess(args=['gedit'], returncode=0)

Depending on your Linux distribution, you may have a different text editor, such as kate, leafpad, kwrite, or enki.

>>>

>>> subprocess.run(["open", "-e"])

CompletedProcess(args=['open', '-e'], returncode=0)

These commands should open up a text editor window. Usually CompletedProcess won’t get returned until you close the editor window. Yet in the case of macOS, since you need to run the launcher process open to launch TextEdit, the CompletedProcess gets returned straight away.

Launcher processes are in charge of launching a specific process and then ending. Sometimes programs, such as web browsers, have them built in. The mechanics of launcher processes is out of the scope of this tutorial, but suffice to say that they’re able to manipulate the operating system’s process tree to reassign parent-child relationships.

You’ve successfully started new processes using Python! That’s subprocess at its most basic. Next up, you’ll take a closer look at the CompletedProcess object that’s returned from run().

The CompletedProcess Object

When you use run(), the return value is an instance of the CompletedProcess class. As the name suggests, run() returns the object only once the child process has ended. It has various attributes that can be helpful, such as the args that were used for the process and the returncode.

To see this clearly, you can assign the result of run() to a variable, and then access its attributes such as .returncode:

>>>

>>> import subprocess

>>> completed_process = subprocess.run(["python", "timer.py"])

usage: timer.py [-h] time

timer.py: error: the following arguments are required: time

>>> completed_process.returncode

2

The process has a return code that indicates failure, but it doesn’t raise an exception. Typically, when a subprocess process fails, you’ll always want an exception to be raised, which you can do by passing in a check=True argument:

>>>

>>> completed_process = subprocess.run(

... ["python", "timer.py"],

... check=True

... )

...

usage: timer.py [-h] time

timer.py: error: the following arguments are required: time

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

subprocess.CalledProcessError: Command '['python', 'timer.py']' returned

non-zero exit status 2.

There are various ways to deal with failures, some of which will be covered in the next section. The important point to note for now is that run() won’t necessarily raise an exception if the process fails unless you’ve passed in a check=True argument.

The CompletedProcess also has a few attributes relating to input/output (I/O), which you’ll cover in more detail in the communicating with processes section. Before communicating with processes, though, you’ll learn how to handle errors when coding with subprocess.

subprocess Exceptions

As you saw earlier, even if a process exits with a return code that represents failure, Python won’t raise an exception. For most use cases of the subprocess module, this isn’t ideal. If a process fails, you’ll usually want to handle it somehow, not just carry on.

A lot of subprocess use cases involve short personal scripts that you might not spend much time on, or at least shouldn’t spend much time on. If you’re tinkering with a script like this, then you’ll want subprocess to fail early and loudly.

CalledProcessError for Non-Zero Exit Code

If a process returns an exit code that isn’t zero, you should interpret that as a failed process. Contrary to what you might expect, the Python subprocess module does not automatically raise an exception on a non-zero exit code. A failing process is typically not something you want your program to pass over silently, so you can pass a check=True argument to run() to raise an exception:

>>>

>>> completed_process = subprocess.run(

... ["python", "timer.py"],

... check=True

... )

...

usage: timer.py [-h] time

timer.py: error: the following arguments are required: time

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

subprocess.CalledProcessError: Command '['python', 'timer.py']' returned

non-zero exit status 2.

The CalledProcessError is raised as soon as the subprocess runs into a non-zero return code. If you’re developing a short personal script, then perhaps this is good enough for you. If you want to handle errors more gracefully, then read on to the section on exception handling.

One thing to bear in mind is that the CalledProcessError does not apply to processes that may hang and block your execution indefinitely. To guard against that, you’d want to take advantage of the timeout parameter.

TimeoutExpired for Processes That Take Too Long

Sometimes processes aren’t well behaved, and they might take too long or just hang indefinitely. To handle those situations, it’s always a good idea to use the timeout parameter of the run() function.

Passing a timeout=1 argument to run() will cause the function to shut down the process and raise a TimeoutExpired error after one second:

>>>

>>> import subprocess

>>> subprocess.run(["python", "timer.py", "5"], timeout=1)

Starting timer of 5 seconds

.Traceback (most recent call last):

...

subprocess.TimeoutExpired: Command '['python', 'timer.py', '5']' timed out

after 1.0 seconds

In this example, the first dot of the timer animation was output, but the subprocess was shut down before being able to complete.

The other type of error that might happen is if the program doesn’t exist on that particular system, which raises one final type of error.

FileNotFoundError for Programs That Don’t Exist

The final type of exception you’ll be looking at is the FileNotFoundError, which is raised if you try and call a program that doesn’t exist on the target system:

>>>

>>> import subprocess

>>> subprocess.run(["now_you_see_me"])

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

FileNotFoundError: The system cannot find the file specified

This type of error is raised no matter what, so you don’t need to pass in any arguments for the FileNotFoundError.

Those are the main exceptions that you’ll run into when using the Python subprocess module. For many use cases, knowing the exceptions and making sure that you use timeout and check arguments will be enough. That’s because if the subprocess fails, then that usually means that your script has failed.

However, if you have a more complex program, then you may want to handle errors more gracefully. For instance, you may need to call many processes over a long period of time. For this, you can use the try … except construct.

An Example of Exception Handling

Here’s a code snippet that shows the main exceptions that you’ll want to handle when using subprocess:

import subprocess

try:

subprocess.run(

["python", "timer.py", "5"], timeout=10, check=True

)

except FileNotFoundError as exc:

print(f"Process failed because the executable could not be found.\n{exc}")

except subprocess.CalledProcessError as exc:

print(

f"Process failed because did not return a successful return code. "

f"Returned {exc.returncode}\n{exc}"

)

except subprocess.TimeoutExpired as exc:

print(f"Process timed out.\n{exc}")

This snippet shows you an example of how you might handle the three main exceptions raised by the subprocess module.

Now that you’ve used subprocess in its basic form and handled some exceptions, it’s time to get familiar with what it takes to interact with the shell.

Introduction to the Shell and Text-Based Programs With subprocess

Some of the most popular use cases of the subprocess module are to interact with text-based programs, typically available on the shell. That’s why in this section, you’ll start to explore all the moving parts involved when interacting with text-based programs, and perhaps question if you need the shell at all!

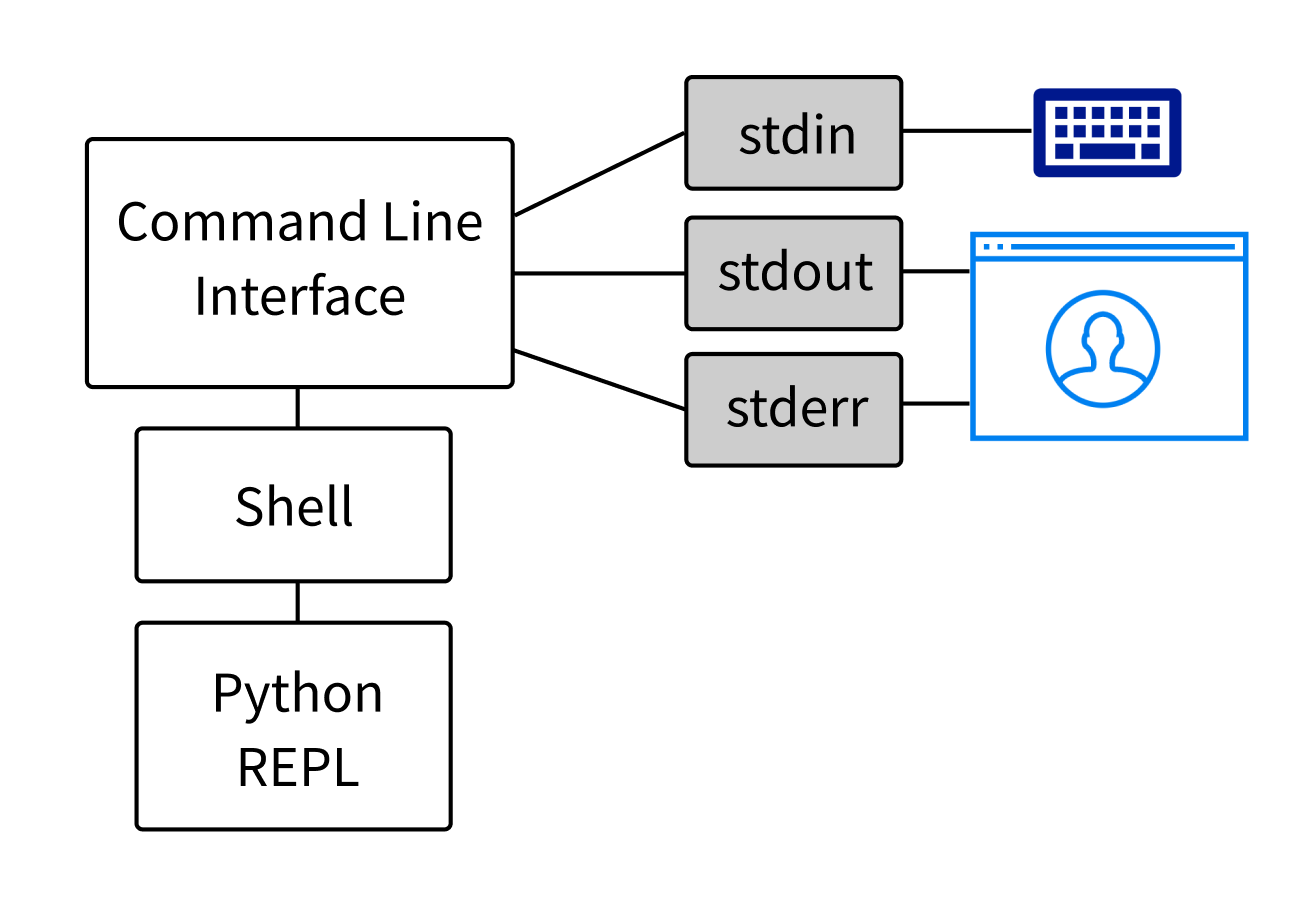

The shell is typically synonymous with the command-line interface or CLI, but this terminology isn’t entirely accurate. There are actually two separate processes that make up the typical command-line experience:

- The interpreter, which is typically thought of as the whole CLI. Common interpreters are Bash on Linux, Zsh on macOS, or PowerShell on Windows. In this tutorial, the interpreter will be referred to as the shell.

- The interface, which displays the output of the interpreter in a window and sends user keystrokes to the interpreter. The interface is a separate process from the shell, sometimes called a terminal emulator.

When on the command line, it’s common to think that you’re interacting directly with the shell, but you’re really interacting with the interface. The interface takes care of sending your commands to the shell and displaying the shell’s output back to you.

With this important distinction in mind, it’s time to turn your attention to what run() is actually doing. It’s common to think that calling run() is somehow the same as typing a command in a terminal interface, but there are important differences.

While all new process are created with the same system calls, the context from which the system call is made is different. The run() function can make a system call directly and doesn’t need to go through the shell to do so:

In fact, many programs that are thought of as shell programs, such as Git, are really just text-based programs that don’t need a shell to run. This is especially true of UNIX environments, where all of the familiar utilities like ls, rm, grep, and cat are actually separate executables that can be called directly:

>>>