Connecting to a Database

psql is a regular PostgreSQL client application. In order to connect to a database you need to know the name of your target database, the host name and port number of the server, and what database user name you want to connect as. psql can be told about those parameters via command line options, namely -d, -h, -p, and -U respectively. If an argument is found that does not belong to any option it will be interpreted as the database name (or the database user name, if the database name is already given). Not all of these options are required; there are useful defaults. If you omit the host name, psql will connect via a Unix-domain socket to a server on the local host, or via TCP/IP to localhost on Windows. The default port number is determined at compile time. Since the database server uses the same default, you will not have to specify the port in most cases. The default database user name is your operating-system user name. Once the database user name is determined, it is used as the default database name. Note that you cannot just connect to any database under any database user name. Your database administrator should have informed you about your access rights.

When the defaults aren’t quite right, you can save yourself some typing by setting the environment variables PGDATABASE, PGHOST, PGPORT and/or PGUSER to appropriate values. (For additional environment variables, see Section 34.15.) It is also convenient to have a ~/.pgpass file to avoid regularly having to type in passwords. See Section 34.16 for more information.

An alternative way to specify connection parameters is in a conninfo string or a URI, which is used instead of a database name. This mechanism give you very wide control over the connection. For example:

$psql "service=myservice sslmode=require"$psql postgresql://dbmaster:5433/mydb?sslmode=require

This way you can also use LDAP for connection parameter lookup as described in Section 34.18. See Section 34.1.2 for more information on all the available connection options.

If the connection could not be made for any reason (e.g., insufficient privileges, server is not running on the targeted host, etc.), psql will return an error and terminate.

If both standard input and standard output are a terminal, then psql sets the client encoding to “auto”, which will detect the appropriate client encoding from the locale settings (LC_CTYPE environment variable on Unix systems). If this doesn’t work out as expected, the client encoding can be overridden using the environment variable PGCLIENTENCODING.

Entering SQL Commands

In normal operation, psql provides a prompt with the name of the database to which psql is currently connected, followed by the string =>. For example:

$ psql testdb

psql (16.0)

Type "help" for help.

testdb=>

At the prompt, the user can type in SQL commands. Ordinarily, input lines are sent to the server when a command-terminating semicolon is reached. An end of line does not terminate a command. Thus commands can be spread over several lines for clarity. If the command was sent and executed without error, the results of the command are displayed on the screen.

If untrusted users have access to a database that has not adopted a secure schema usage pattern, begin your session by removing publicly-writable schemas from search_path. One can add options=-csearch_path= to the connection string or issue SELECT pg_catalog.set_config('search_path', '', false) before other SQL commands. This consideration is not specific to psql; it applies to every interface for executing arbitrary SQL commands.

Whenever a command is executed, psql also polls for asynchronous notification events generated by LISTEN and NOTIFY.

While C-style block comments are passed to the server for processing and removal, SQL-standard comments are removed by psql.

Advanced Features

Variables

psql provides variable substitution features similar to common Unix command shells. Variables are simply name/value pairs, where the value can be any string of any length. The name must consist of letters (including non-Latin letters), digits, and underscores.

To set a variable, use the psql meta-command \set. For example,

testdb=> \set foo bar

sets the variable foo to the value bar. To retrieve the content of the variable, precede the name with a colon, for example:

testdb=> \echo :foo

bar

This works in both regular SQL commands and meta-commands; there is more detail in SQL Interpolation, below.

If you call \set without a second argument, the variable is set to an empty-string value. To unset (i.e., delete) a variable, use the command \unset. To show the values of all variables, call \set without any argument.

Note

The arguments of \set are subject to the same substitution rules as with other commands. Thus you can construct interesting references such as \set :foo 'something' and get “soft links” or “variable variables” of Perl or PHP fame, respectively. Unfortunately (or fortunately?), there is no way to do anything useful with these constructs. On the other hand, \set bar :foo is a perfectly valid way to copy a variable.

A number of these variables are treated specially by psql. They represent certain option settings that can be changed at run time by altering the value of the variable, or in some cases represent changeable state of psql. By convention, all specially treated variables’ names consist of all upper-case ASCII letters (and possibly digits and underscores). To ensure maximum compatibility in the future, avoid using such variable names for your own purposes.

Variables that control psql‘s behavior generally cannot be unset or set to invalid values. An \unset command is allowed but is interpreted as setting the variable to its default value. A \set command without a second argument is interpreted as setting the variable to on, for control variables that accept that value, and is rejected for others. Also, control variables that accept the values on and off will also accept other common spellings of Boolean values, such as true and false.

The specially treated variables are:

AUTOCOMMIT#-

When

on(the default), each SQL command is automatically committed upon successful completion. To postpone commit in this mode, you must enter aBEGINorSTART TRANSACTIONSQL command. Whenoffor unset, SQL commands are not committed until you explicitly issueCOMMITorEND. The autocommit-off mode works by issuing an implicitBEGINfor you, just before any command that is not already in a transaction block and is not itself aBEGINor other transaction-control command, nor a command that cannot be executed inside a transaction block (such asVACUUM).Note

In autocommit-off mode, you must explicitly abandon any failed transaction by entering

ABORTorROLLBACK. Also keep in mind that if you exit the session without committing, your work will be lost.Note

The autocommit-on mode is PostgreSQL‘s traditional behavior, but autocommit-off is closer to the SQL spec. If you prefer autocommit-off, you might wish to set it in the system-wide

psqlrcfile or your~/.psqlrcfile. COMP_KEYWORD_CASE#-

Determines which letter case to use when completing an SQL key word. If set to

lowerorupper, the completed word will be in lower or upper case, respectively. If set topreserve-lowerorpreserve-upper(the default), the completed word will be in the case of the word already entered, but words being completed without anything entered will be in lower or upper case, respectively. DBNAME#-

The name of the database you are currently connected to. This is set every time you connect to a database (including program start-up), but can be changed or unset.

ECHO#-

If set to

all, all nonempty input lines are printed to standard output as they are read. (This does not apply to lines read interactively.) To select this behavior on program start-up, use the switch-a. If set toqueries, psql prints each query to standard output as it is sent to the server. The switch to select this behavior is-e. If set toerrors, then only failed queries are displayed on standard error output. The switch for this behavior is-b. If set tonone(the default), then no queries are displayed. ECHO_HIDDEN#-

When this variable is set to

onand a backslash command queries the database, the query is first shown. This feature helps you to study PostgreSQL internals and provide similar functionality in your own programs. (To select this behavior on program start-up, use the switch-E.) If you set this variable to the valuenoexec, the queries are just shown but are not actually sent to the server and executed. The default value isoff. ENCODING#-

The current client character set encoding. This is set every time you connect to a database (including program start-up), and when you change the encoding with

\encoding, but it can be changed or unset. ERROR#-

trueif the last SQL query failed,falseif it succeeded. See alsoSQLSTATE. FETCH_COUNT#-

If this variable is set to an integer value greater than zero, the results of

SELECTqueries are fetched and displayed in groups of that many rows, rather than the default behavior of collecting the entire result set before display. Therefore only a limited amount of memory is used, regardless of the size of the result set. Settings of 100 to 1000 are commonly used when enabling this feature. Keep in mind that when using this feature, a query might fail after having already displayed some rows.Tip

Although you can use any output format with this feature, the default

alignedformat tends to look bad because each group ofFETCH_COUNTrows will be formatted separately, leading to varying column widths across the row groups. The other output formats work better. HIDE_TABLEAM#-

If this variable is set to

true, a table’s access method details are not displayed. This is mainly useful for regression tests. HIDE_TOAST_COMPRESSION#-

If this variable is set to

true, column compression method details are not displayed. This is mainly useful for regression tests. HISTCONTROL#-

If this variable is set to

ignorespace, lines which begin with a space are not entered into the history list. If set to a value ofignoredups, lines matching the previous history line are not entered. A value ofignorebothcombines the two options. If set tonone(the default), all lines read in interactive mode are saved on the history list.Note

This feature was shamelessly plagiarized from Bash.

HISTFILE#-

The file name that will be used to store the history list. If unset, the file name is taken from the

PSQL_HISTORYenvironment variable. If that is not set either, the default is~/.psql_history, or%APPDATA%\postgresql\psql_historyon Windows. For example, putting:\set HISTFILE ~/.psql_history-:DBNAME

in

~/.psqlrcwill cause psql to maintain a separate history for each database.Note

This feature was shamelessly plagiarized from Bash.

HISTSIZE#-

The maximum number of commands to store in the command history (default 500). If set to a negative value, no limit is applied.

Note

This feature was shamelessly plagiarized from Bash.

HOST#-

The database server host you are currently connected to. This is set every time you connect to a database (including program start-up), but can be changed or unset.

IGNOREEOF#-

If set to 1 or less, sending an EOF character (usually Control+D) to an interactive session of psql will terminate the application. If set to a larger numeric value, that many consecutive EOF characters must be typed to make an interactive session terminate. If the variable is set to a non-numeric value, it is interpreted as 10. The default is 0.

Note

This feature was shamelessly plagiarized from Bash.

LASTOID#-

The value of the last affected OID, as returned from an

INSERTor\lo_importcommand. This variable is only guaranteed to be valid until after the result of the next SQL command has been displayed. PostgreSQL servers since version 12 do not support OID system columns anymore, thus LASTOID will always be 0 followingINSERTwhen targeting such servers. LAST_ERROR_MESSAGELAST_ERROR_SQLSTATE#-

The primary error message and associated SQLSTATE code for the most recent failed query in the current psql session, or an empty string and

00000if no error has occurred in the current session. ON_ERROR_ROLLBACK#-

When set to

on, if a statement in a transaction block generates an error, the error is ignored and the transaction continues. When set tointeractive, such errors are only ignored in interactive sessions, and not when reading script files. When set tooff(the default), a statement in a transaction block that generates an error aborts the entire transaction. The error rollback mode works by issuing an implicitSAVEPOINTfor you, just before each command that is in a transaction block, and then rolling back to the savepoint if the command fails. ON_ERROR_STOP#-

By default, command processing continues after an error. When this variable is set to

on, processing will instead stop immediately. In interactive mode, psql will return to the command prompt; otherwise, psql will exit, returning error code 3 to distinguish this case from fatal error conditions, which are reported using error code 1. In either case, any currently running scripts (the top-level script, if any, and any other scripts which it may have in invoked) will be terminated immediately. If the top-level command string contained multiple SQL commands, processing will stop with the current command. PORT#-

The database server port to which you are currently connected. This is set every time you connect to a database (including program start-up), but can be changed or unset.

PROMPT1PROMPT2PROMPT3#-

These specify what the prompts psql issues should look like. See Prompting below.

QUIET#-

Setting this variable to

onis equivalent to the command line option-q. It is probably not too useful in interactive mode. ROW_COUNT#-

The number of rows returned or affected by the last SQL query, or 0 if the query failed or did not report a row count.

SERVER_VERSION_NAMESERVER_VERSION_NUM#-

The server’s version number as a string, for example

9.6.2,10.1or11beta1, and in numeric form, for example90602or100001. These are set every time you connect to a database (including program start-up), but can be changed or unset. SHELL_ERROR#-

trueif the last shell command failed,falseif it succeeded. This applies to shell commands invoked via the\!,\g,\o,\w, and\copymeta-commands, as well as backquote (`) expansion. Note that for\o, this variable is updated when the output pipe is closed by the next\ocommand. See alsoSHELL_EXIT_CODE. SHELL_EXIT_CODE#-

The exit status returned by the last shell command. 0–127 represent program exit codes, 128–255 indicate termination by a signal, and -1 indicates failure to launch a program or to collect its exit status. This applies to shell commands invoked via the

\!,\g,\o,\w, and\copymeta-commands, as well as backquote (`) expansion. Note that for\o, this variable is updated when the output pipe is closed by the next\ocommand. See alsoSHELL_ERROR. SHOW_ALL_RESULTS#-

When this variable is set to

off, only the last result of a combined query (\;) is shown instead of all of them. The default ison. The off behavior is for compatibility with older versions of psql. SHOW_CONTEXT#-

This variable can be set to the values

never,errors, oralwaysto control whetherCONTEXTfields are displayed in messages from the server. The default iserrors(meaning that context will be shown in error messages, but not in notice or warning messages). This setting has no effect whenVERBOSITYis set toterseorsqlstate. (See also\errverbose, for use when you want a verbose version of the error you just got.) SINGLELINE#-

Setting this variable to

onis equivalent to the command line option-S. SINGLESTEP#-

Setting this variable to

onis equivalent to the command line option-s. SQLSTATE#-

The error code (see Appendix A) associated with the last SQL query’s failure, or

00000if it succeeded. USER#-

The database user you are currently connected as. This is set every time you connect to a database (including program start-up), but can be changed or unset.

VERBOSITY#-

This variable can be set to the values

default,verbose,terse, orsqlstateto control the verbosity of error reports. (See also\errverbose, for use when you want a verbose version of the error you just got.) VERSIONVERSION_NAMEVERSION_NUM#-

These variables are set at program start-up to reflect psql‘s version, respectively as a verbose string, a short string (e.g.,

9.6.2,10.1, or11beta1), and a number (e.g.,90602or100001). They can be changed or unset.

SQL Interpolation

A key feature of psql variables is that you can substitute (“interpolate”) them into regular SQL statements, as well as the arguments of meta-commands. Furthermore, psql provides facilities for ensuring that variable values used as SQL literals and identifiers are properly quoted. The syntax for interpolating a value without any quoting is to prepend the variable name with a colon (:). For example,

testdb=>\set foo 'my_table'testdb=>SELECT * FROM :foo;

would query the table my_table. Note that this may be unsafe: the value of the variable is copied literally, so it can contain unbalanced quotes, or even backslash commands. You must make sure that it makes sense where you put it.

When a value is to be used as an SQL literal or identifier, it is safest to arrange for it to be quoted. To quote the value of a variable as an SQL literal, write a colon followed by the variable name in single quotes. To quote the value as an SQL identifier, write a colon followed by the variable name in double quotes. These constructs deal correctly with quotes and other special characters embedded within the variable value. The previous example would be more safely written this way:

testdb=>\set foo 'my_table'testdb=>SELECT * FROM :"foo";

Variable interpolation will not be performed within quoted SQL literals and identifiers. Therefore, a construction such as ':foo' doesn’t work to produce a quoted literal from a variable’s value (and it would be unsafe if it did work, since it wouldn’t correctly handle quotes embedded in the value).

One example use of this mechanism is to copy the contents of a file into a table column. First load the file into a variable and then interpolate the variable’s value as a quoted string:

testdb=>\set content `cat my_file.txt`testdb=>INSERT INTO my_table VALUES (:'content');

(Note that this still won’t work if my_file.txt contains NUL bytes. psql does not support embedded NUL bytes in variable values.)

Since colons can legally appear in SQL commands, an apparent attempt at interpolation (that is, :name, :'name', or :"name") is not replaced unless the named variable is currently set. In any case, you can escape a colon with a backslash to protect it from substitution.

The :{? special syntax returns TRUE or FALSE depending on whether the variable exists or not, and is thus always substituted, unless the colon is backslash-escaped.name}

The colon syntax for variables is standard SQL for embedded query languages, such as ECPG. The colon syntaxes for array slices and type casts are PostgreSQL extensions, which can sometimes conflict with the standard usage. The colon-quote syntax for escaping a variable’s value as an SQL literal or identifier is a psql extension.

Prompting

The prompts psql issues can be customized to your preference. The three variables PROMPT1, PROMPT2, and PROMPT3 contain strings and special escape sequences that describe the appearance of the prompt. Prompt 1 is the normal prompt that is issued when psql requests a new command. Prompt 2 is issued when more input is expected during command entry, for example because the command was not terminated with a semicolon or a quote was not closed. Prompt 3 is issued when you are running an SQL COPY FROM STDIN command and you need to type in a row value on the terminal.

The value of the selected prompt variable is printed literally, except where a percent sign (%) is encountered. Depending on the next character, certain other text is substituted instead. Defined substitutions are:

%M#-

The full host name (with domain name) of the database server, or

[local]if the connection is over a Unix domain socket, or[local:, if the Unix domain socket is not at the compiled in default location./dir/name] %m#-

The host name of the database server, truncated at the first dot, or

[local]if the connection is over a Unix domain socket. %>#-

The port number at which the database server is listening.

%n#-

The database session user name. (The expansion of this value might change during a database session as the result of the command

SET SESSION AUTHORIZATION.) %/#-

The name of the current database.

%~#-

Like

%/, but the output is~(tilde) if the database is your default database. %##-

If the session user is a database superuser, then a

#, otherwise a>. (The expansion of this value might change during a database session as the result of the commandSET SESSION AUTHORIZATION.) %p#-

The process ID of the backend currently connected to.

%R#-

In prompt 1 normally

=, but@if the session is in an inactive branch of a conditional block, or^if in single-line mode, or!if the session is disconnected from the database (which can happen if\connectfails). In prompt 2%Ris replaced by a character that depends on why psql expects more input:-if the command simply wasn’t terminated yet, but*if there is an unfinished/* ... */comment, a single quote if there is an unfinished quoted string, a double quote if there is an unfinished quoted identifier, a dollar sign if there is an unfinished dollar-quoted string, or(if there is an unmatched left parenthesis. In prompt 3%Rdoesn’t produce anything. %x#-

Transaction status: an empty string when not in a transaction block, or

*when in a transaction block, or!when in a failed transaction block, or?when the transaction state is indeterminate (for example, because there is no connection). %l#-

The line number inside the current statement, starting from

1. %digits#-

The character with the indicated octal code is substituted.

%:name:#-

The value of the psql variable

name. See Variables, above, for details. %`command`#-

The output of

command, similar to ordinary “back-tick” substitution. %[…%]#-

Prompts can contain terminal control characters which, for example, change the color, background, or style of the prompt text, or change the title of the terminal window. In order for the line editing features of Readline to work properly, these non-printing control characters must be designated as invisible by surrounding them with

%[and%]. Multiple pairs of these can occur within the prompt. For example:testdb=> \set PROMPT1 '%[%033[1;33;40m%]%n@%/%R%[%033[0m%]%# '

results in a boldfaced (

1;) yellow-on-black (33;40) prompt on VT100-compatible, color-capable terminals. %w#-

Whitespace of the same width as the most recent output of

PROMPT1. This can be used as aPROMPT2setting, so that multi-line statements are aligned with the first line, but there is no visible secondary prompt.

To insert a percent sign into your prompt, write %%. The default prompts are '%/%R%x%# ' for prompts 1 and 2, and '>> ' for prompt 3.

Note

This feature was shamelessly plagiarized from tcsh.

Command-Line Editing

psql uses the Readline or libedit library, if available, for convenient line editing and retrieval. The command history is automatically saved when psql exits and is reloaded when psql starts up. Type up-arrow or control-P to retrieve previous lines.

You can also use tab completion to fill in partially-typed keywords and SQL object names in many (by no means all) contexts. For example, at the start of a command, typing ins and pressing TAB will fill in insert into . Then, typing a few characters of a table or schema name and pressing TAB will fill in the unfinished name, or offer a menu of possible completions when there’s more than one. (Depending on the library in use, you may need to press TAB more than once to get a menu.)

Tab completion for SQL object names requires sending queries to the server to find possible matches. In some contexts this can interfere with other operations. For example, after BEGIN it will be too late to issue SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL if a tab-completion query is issued in between. If you do not want tab completion at all, you can turn it off permanently by putting this in a file named .inputrc in your home directory:

$if psql set disable-completion on $endif

(This is not a psql but a Readline feature. Read its documentation for further details.)

The -n (--no-readline) command line option can also be useful to disable use of Readline for a single run of psql. This prevents tab completion, use or recording of command line history, and editing of multi-line commands. It is particularly useful when you need to copy-and-paste text that contains TAB characters.

Материал из Кафедра ИУ5 МГТУ им. Н.Э.Баумана — студенческое сообщество

В статье пойдёт речь о том, как добиться корректного вывода кириллицы в «консоли» Windows (cmd.exe).

Содержание

- 1 Описание проблемы

- 2 Решение проблемы

- 2.1 Суть

- 2.2 Конкретные действия

- 2.2.1 Супер быстро и просто

- 2.2.2 Быстро и просто

- 2.2.3 Посложнее и подольше

Описание проблемы

В дистрибутив PostgreSQL, помимо всего прочего, для работы с СУБД входит:

- приложение с графическим интерфейсом

pgAdmin; - консольная утилита

psql.

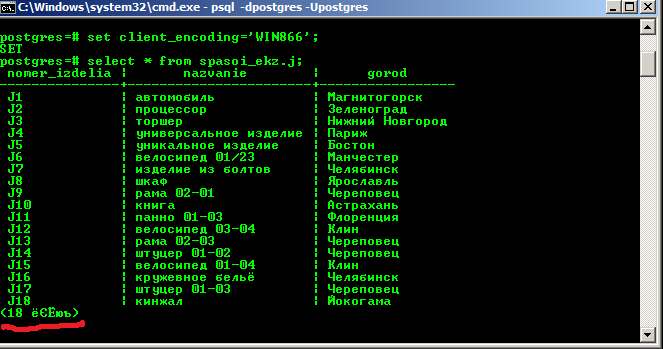

При работе с psql в среде Windows пользователи всегда довольно часто сталкиваются с проблемой вывода кириллицы. Например, при отображении результатов запроса к таблице, в полях которых хранятся строковые данные на русском языке.

Ну и зачем тогда работать с psql, кому нужно долбить клавиатурой в консольке, когда можно всё сделать красиво и быстро в pgAdmin? Ну, не всегда pgAdmin доступен, особенно если речь идёт об удалённой машине. Кроме того, выполнение SQL-запросов в текстовом режиме консоли — это +10 к хакирству.

Решение проблемы

Версии ПО:

- MS Windows 7 SP1 x64;

- PostgreSQL 8.4.12 x32.

На сервере имеется БД, созданная в кодировке UTF8.

Суть

Суть проблемы в том, что cmd.exe работает (и так будет до скончания времён) в кодировке CP866, а сама Windows — в WIN1251, о чём psql предупреждает при начале работы:

WARNING: Console code page (866) differs from Windows code page (1251)

8-bit characters might not work correctly. See psql reference

page "Notes for Windows users" for details.

Значит, надо как-то добиться, чтобы кодировка была одна.

В разных источниках встречаются разные рецепты, включая правку реестра и подмену файлов в системных папках Windows. Ничего этого делать не нужно, достаточно всего трёх шагов:

- сменить шрифт у

cmd.exe; - сменить текущую кодовую страницу

cmd.exe; - сменить кодировку на стороне клиента в

psql.

Конкретные действия

Супер быстро и просто

Запускаете cmd.exe, оттуда psql:

psql -d ВАШАБАЗА -U ВАШЛОГИН

Далее:

psql \! chcp 1251

Быстро и просто

Запускаете cmd.exe, оттуда psql:

psql -d ВАШАБАЗА -U ВАШЛОГИН

Вводите пароль (если установлен) и выполняете команду:

set client_encoding='WIN866';

И всё. Теперь результаты запроса, содержащие кириллицу, будут отображаться нормально. Но есть небольшой косяк:

Потому предлагаем ещё способ, который этого недостатка лишён.

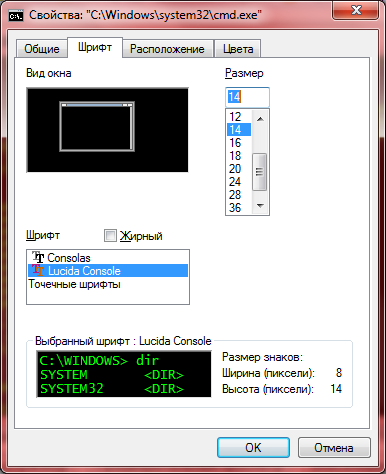

Посложнее и подольше

Запустить cmd.exe, нажать мышью в правом левом верхнем углу окна, там Свойства — Шрифт — выбрать Lucida Console. Нажать ОК.

Выполнить команду:

chcp 1251

В ответ выведет:

Текущая кодовая страница: 1251

Запустить psql;

psql -d ВАШАБАЗА -U ВАШЛОГИН

Кстати, обратите внимание — теперь предупреждения о несовпадении кодировок нет.

Выполнить:

set client_encoding='win1251';

Он выведет:

SET

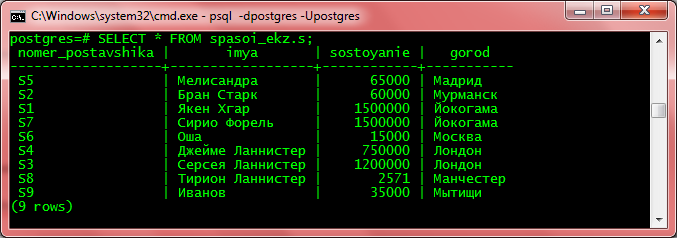

Всё, теперь кириллица будет нормально отображаться.

Проверяем:

NAME¶

psql — PostgreSQL interactive terminal

SYNOPSIS¶

psql [option…]

[dbname [username]]

DESCRIPTION¶

psql is a terminal-based front-end to PostgreSQL. It enables you

to type in queries interactively, issue them to PostgreSQL, and see the

query results. Alternatively, input can be from a file or from command line

arguments. In addition, psql provides a number of meta-commands and various

shell-like features to facilitate writing scripts and automating a wide

variety of tasks.

OPTIONS¶

-a

—echo-all

Print all nonempty input lines to standard output as they

are read. (This does not apply to lines read interactively.) This is

equivalent to setting the variable ECHO to all.

-A

—no-align

Switches to unaligned output mode. (The default output

mode is otherwise aligned.) This is equivalent to \pset format

unaligned.

-b

—echo-errors

Print failed SQL commands to standard error output. This

is equivalent to setting the variable ECHO to errors.

-c command

—command=command

Specifies that psql is to execute the given command

string, command. This option can be repeated and combined in any order

with the -f option. When either -c or -f is specified,

psql does not read commands from standard input; instead it terminates after

processing all the -c and -f options in sequence.

command must be either a command string that is completely

parsable by the server (i.e., it contains no psql-specific features), or a

single backslash command. Thus you cannot mix SQL and psql meta-commands

within a -c option. To achieve that, you could use repeated -c

options or pipe the string into psql, for example:

psql -c '\x' -c 'SELECT * FROM foo;'

or

echo '\x \\ SELECT * FROM foo;' | psql

(\\ is the separator meta-command.)

Each SQL command string passed to -c is sent to the server

as a single query. Because of this, the server executes it as a single

transaction even if the string contains multiple SQL commands, unless there

are explicit BEGIN/COMMIT commands included in the string to

divide it into multiple transactions. Also, psql only prints the result of

the last SQL command in the string. This is different from the behavior when

the same string is read from a file or fed to psql’s standard input, because

then psql sends each SQL command separately.

Because of this behavior, putting more than one command in a

single -c string often has unexpected results. It’s better to use

repeated -c commands or feed multiple commands to psql’s standard

input, either using echo as illustrated above, or via a shell here-document,

for example:

psql <<EOF \x SELECT * FROM foo; EOF

-d dbname

—dbname=dbname

Specifies the name of the database to connect to. This is

equivalent to specifying dbname as the first non-option argument on the

command line.

If this parameter contains an = sign or starts with a valid URI

prefix (postgresql:// or postgres://), it is treated as a conninfo

string. See Section 33.1.1 for more information.

-e

—echo-queries

Copy all SQL commands sent to the server to standard

output as well. This is equivalent to setting the variable ECHO to

queries.

-E

—echo-hidden

Echo the actual queries generated by \d and other

backslash commands. You can use this to study psql’s internal operations. This

is equivalent to setting the variable ECHO_HIDDEN to on.

-f filename

—file=filename

Read commands from the file filename, rather than

standard input. This option can be repeated and combined in any order with the

-c option. When either -c or -f is specified, psql does

not read commands from standard input; instead it terminates after processing

all the -c and -f options in sequence. Except for that, this

option is largely equivalent to the meta-command \i.

If filename is — (hyphen), then standard input is read

until an EOF indication or \q meta-command. This can be used to

intersperse interactive input with input from files. Note however that

Readline is not used in this case (much as if -n had been

specified).

Using this option is subtly different from writing psql <

filename. In general, both will do what you expect, but using -f

enables some nice features such as error messages with line numbers. There

is also a slight chance that using this option will reduce the start-up

overhead. On the other hand, the variant using the shell’s input redirection

is (in theory) guaranteed to yield exactly the same output you would have

received had you entered everything by hand.

-F separator

—field-separator=separator

Use separator as the field separator for unaligned

output. This is equivalent to \pset fieldsep or \f.

-h hostname

—host=hostname

Specifies the host name of the machine on which the

server is running. If the value begins with a slash, it is used as the

directory for the Unix-domain socket.

-H

—html

Turn on HTML tabular output. This is equivalent to \pset

format html or the \H command.

-l

—list

List all available databases, then exit. Other

non-connection options are ignored. This is similar to the meta-command

\list.

When this option is used, psql will connect to the database

postgres, unless a different database is named on the command line (option

-d or non-option argument, possibly via a service entry, but not via

an environment variable).

-L filename

—log-file=filename

Write all query output into file filename, in

addition to the normal output destination.

-n

—no-readline

Do not use Readline for line editing and do not use the

command history. This can be useful to turn off tab expansion when cutting and

pasting.

-o filename

—output=filename

Put all query output into file filename. This is

equivalent to the command \o.

-p port

—port=port

Specifies the TCP port or the local Unix-domain socket

file extension on which the server is listening for connections. Defaults to

the value of the PGPORT environment variable or, if not set, to the

port specified at compile time, usually 5432.

-P assignment

—pset=assignment

Specifies printing options, in the style of \pset.

Note that here you have to separate name and value with an equal sign instead

of a space. For example, to set the output format to LaTeX, you could write -P

format=latex.

-q

—quiet

Specifies that psql should do its work quietly. By

default, it prints welcome messages and various informational output. If this

option is used, none of this happens. This is useful with the -c

option. This is equivalent to setting the variable QUIET to on.

-R separator

—record-separator=separator

Use separator as the record separator for

unaligned output. This is equivalent to \pset recordsep.

-s

—single-step

Run in single-step mode. That means the user is prompted

before each command is sent to the server, with the option to cancel execution

as well. Use this to debug scripts.

-S

—single-line

Runs in single-line mode where a newline terminates an

SQL command, as a semicolon does.

Note

This mode is provided for those who insist on it, but you are not necessarily

encouraged to use it. In particular, if you mix SQL and meta-commands on a

line the order of execution might not always be clear to the inexperienced

user.

-t

—tuples-only

Turn off printing of column names and result row count

footers, etc. This is equivalent to \t or \pset

tuples_only.

-T table_options

—table-attr=table_options

Specifies options to be placed within the HTML table tag.

See \pset tableattr for details.

-U username

—username=username

Connect to the database as the user username

instead of the default. (You must have permission to do so, of course.)

-v assignment

—set=assignment

—variable=assignment

Perform a variable assignment, like the \set

meta-command. Note that you must separate name and value, if any, by an equal

sign on the command line. To unset a variable, leave off the equal sign. To

set a variable with an empty value, use the equal sign but leave off the

value. These assignments are done during command line processing, so variables

that reflect connection state will get overwritten later.

-V

—version

Print the psql version and exit.

-w

—no-password

Never issue a password prompt. If the server requires

password authentication and a password is not available by other means such as

a .pgpass file, the connection attempt will fail. This option can be useful in

batch jobs and scripts where no user is present to enter a password.

Note that this option will remain set for the entire session, and

so it affects uses of the meta-command \connect as well as the

initial connection attempt.

-W

—password

Force psql to prompt for a password before connecting to

a database.

This option is never essential, since psql will automatically

prompt for a password if the server demands password authentication.

However, psql will waste a connection attempt finding out that the server

wants a password. In some cases it is worth typing -W to avoid the

extra connection attempt.

Note that this option will remain set for the entire session, and

so it affects uses of the meta-command \connect as well as the

initial connection attempt.

-x

—expanded

Turn on the expanded table formatting mode. This is

equivalent to \x or \pset expanded.

-X,

—no-psqlrc

Do not read the start-up file (neither the system-wide

psqlrc file nor the user’s ~/.psqlrc file).

-z

—field-separator-zero

Set the field separator for unaligned output to a zero

byte. This is equivalent to \pset fieldsep_zero.

-0

—record-separator-zero

Set the record separator for unaligned output to a zero

byte. This is useful for interfacing, for example, with xargs -0. This is

equivalent to \pset recordsep_zero.

-1

—single-transaction

This option can only be used in combination with one or

more -c and/or -f options. It causes psql to issue a

BEGIN command before the first such option and a COMMIT command

after the last one, thereby wrapping all the commands into a single

transaction. This ensures that either all the commands complete successfully,

or no changes are applied.

If the commands themselves contain BEGIN, COMMIT, or

ROLLBACK, this option will not have the desired effects. Also, if an

individual command cannot be executed inside a transaction block, specifying

this option will cause the whole transaction to fail.

-?

—help[=topic]

Show help about psql and exit. The optional topic

parameter (defaulting to options) selects which part of psql is explained:

commands describes psql’s backslash commands; options describes the

command-line options that can be passed to psql; and variables shows help

about psql configuration variables.

EXIT STATUS¶

psql returns 0 to the shell if it finished normally, 1 if a fatal

error of its own occurs (e.g. out of memory, file not found), 2 if the

connection to the server went bad and the session was not interactive, and 3

if an error occurred in a script and the variable ON_ERROR_STOP was

set.

USAGE¶

Connecting to a Database¶

psql is a regular PostgreSQL client application. In order to

connect to a database you need to know the name of your target database, the

host name and port number of the server, and what user name you want to

connect as. psql can be told about those parameters via command line

options, namely -d, -h, -p, and -U respectively.

If an argument is found that does not belong to any option it will be

interpreted as the database name (or the user name, if the database name is

already given). Not all of these options are required; there are useful

defaults. If you omit the host name, psql will connect via a Unix-domain

socket to a server on the local host, or via TCP/IP to localhost on machines

that don’t have Unix-domain sockets. The default port number is determined

at compile time. Since the database server uses the same default, you will

not have to specify the port in most cases. The default user name is your

operating-system user name, as is the default database name. Note that you

cannot just connect to any database under any user name. Your database

administrator should have informed you about your access rights.

When the defaults aren’t quite right, you can save yourself some

typing by setting the environment variables PGDATABASE,

PGHOST, PGPORT and/or PGUSER to appropriate values.

(For additional environment variables, see Section 33.14.) It is also

convenient to have a ~/.pgpass file to avoid regularly having to type in

passwords. See Section 33.15 for more information.

An alternative way to specify connection parameters is in a

conninfo string or a URI, which is used instead of a database name.

This mechanism give you very wide control over the connection. For

example:

This way you can also use LDAP for connection parameter lookup as

described in Section 33.17. See Section 33.1.2 for more

information on all the available connection options.

If the connection could not be made for any reason (e.g.,

insufficient privileges, server is not running on the targeted host, etc.),

psql will return an error and terminate.

If both standard input and standard output are a terminal, then

psql sets the client encoding to “auto”, which will detect the

appropriate client encoding from the locale settings (LC_CTYPE

environment variable on Unix systems). If this doesn’t work out as expected,

the client encoding can be overridden using the environment variable

PGCLIENTENCODING.

Entering SQL Commands¶

In normal operation, psql provides a prompt with the name of the

database to which psql is currently connected, followed by the string =>.

For example:

$ psql testdb psql (10.5) Type "help" for help. testdb=>

At the prompt, the user can type in SQL commands. Ordinarily,

input lines are sent to the server when a command-terminating semicolon is

reached. An end of line does not terminate a command. Thus commands can be

spread over several lines for clarity. If the command was sent and executed

without error, the results of the command are displayed on the screen.

If untrusted users have access to a database that has not adopted

a secure schema usage pattern, begin your session by removing

publicly-writable schemas from search_path. One can add

options=-csearch_path= to the connection string or issue SELECT

pg_catalog.set_config(‘search_path’, », false) before other SQL commands.

This consideration is not specific to psql; it applies to every interface

for executing arbitrary SQL commands.

Whenever a command is executed, psql also polls for asynchronous

notification events generated by LISTEN(7) and NOTIFY(7).

While C-style block comments are passed to the server for

processing and removal, SQL-standard comments are removed by psql.

Anything you enter in psql that begins with an unquoted backslash

is a psql meta-command that is processed by psql itself. These commands make

psql more useful for administration or scripting. Meta-commands are often

called slash or backslash commands.

The format of a psql command is the backslash, followed

immediately by a command verb, then any arguments. The arguments are

separated from the command verb and each other by any number of whitespace

characters.

To include whitespace in an argument you can quote it with single

quotes. To include a single quote in an argument, write two single quotes

within single-quoted text. Anything contained in single quotes is

furthermore subject to C-like substitutions for \n (new line), \t (tab), \b

(backspace), \r (carriage return), \f (form feed), \digits (octal),

and \xdigits (hexadecimal). A backslash preceding any other character

within single-quoted text quotes that single character, whatever it is.

If an unquoted colon (:) followed by a psql variable name appears

within an argument, it is replaced by the variable’s value, as described in

SQL Interpolation. The forms :’variable_name‘ and

:»variable_name» described there work as well.

Within an argument, text that is enclosed in backquotes (`) is

taken as a command line that is passed to the shell. The output of the

command (with any trailing newline removed) replaces the backquoted text.

Within the text enclosed in backquotes, no special quoting or other

processing occurs, except that appearances of :variable_name where

variable_name is a psql variable name are replaced by the variable’s

value. Also, appearances of :’variable_name‘ are replaced by the

variable’s value suitably quoted to become a single shell command argument.

(The latter form is almost always preferable, unless you are very sure of

what is in the variable.) Because carriage return and line feed characters

cannot be safely quoted on all platforms, the :’variable_name‘ form

prints an error message and does not substitute the variable value when such

characters appear in the value.

Some commands take an SQL identifier (such as a table name) as

argument. These arguments follow the syntax rules of SQL: Unquoted letters

are forced to lowercase, while double quotes («) protect letters from

case conversion and allow incorporation of whitespace into the identifier.

Within double quotes, paired double quotes reduce to a single double quote

in the resulting name. For example, FOO»BAR»BAZ is interpreted as

fooBARbaz, and «A weird»» name» becomes A weird»

name.

Parsing for arguments stops at the end of the line, or when

another unquoted backslash is found. An unquoted backslash is taken as the

beginning of a new meta-command. The special sequence \\ (two backslashes)

marks the end of arguments and continues parsing SQL commands, if any. That

way SQL and psql commands can be freely mixed on a line. But in any case,

the arguments of a meta-command cannot continue beyond the end of the

line.

Many of the meta-commands act on the current query buffer. This is

simply a buffer holding whatever SQL command text has been typed but not yet

sent to the server for execution. This will include previous input lines as

well as any text appearing before the meta-command on the same line.

The following meta-commands are defined:

\a

If the current table output format is unaligned, it is

switched to aligned. If it is not unaligned, it is set to unaligned. This

command is kept for backwards compatibility. See \pset for a more

general solution.

\c or \connect [ -reuse-previous=on|off ] [ dbname [

username ] [ host ] [ port ] | conninfo ]

Establishes a new connection to a PostgreSQL server. The

connection parameters to use can be specified either using a positional

syntax, or using conninfo connection strings as detailed in

Section 33.1.1.

Where the command omits database name, user, host, or port, the

new connection can reuse values from the previous connection. By default,

values from the previous connection are reused except when processing a

conninfo string. Passing a first argument of -reuse-previous=on or

-reuse-previous=off overrides that default. When the command neither

specifies nor reuses a particular parameter, the libpq default is used.

Specifying any of dbname, username, host or port

as — is equivalent to omitting that parameter.

If the new connection is successfully made, the previous

connection is closed. If the connection attempt failed (wrong user name,

access denied, etc.), the previous connection will only be kept if psql is

in interactive mode. When executing a non-interactive script, processing

will immediately stop with an error. This distinction was chosen as a user

convenience against typos on the one hand, and a safety mechanism that

scripts are not accidentally acting on the wrong database on the other

hand.

Examples:

\C [ title ]

Sets the title of any tables being printed as the result

of a query or unset any such title. This command is equivalent to \pset title

title. (The name of this command derives from “caption”,

as it was previously only used to set the caption in an HTML table.)

\cd [ directory ]

Changes the current working directory to

directory. Without argument, changes to the current user’s home

directory.

Tip

To print your current working directory, use \! pwd.

\conninfo

Outputs information about the current database

connection.

\copy { table [ ( column_list ) ] | ( query )

} { from | to } { ‘filename’ | program ‘command’ | stdin |

stdout | pstdin | pstdout } [ [ with ] ( option [, …] ) ]

Performs a frontend (client) copy. This is an operation

that runs an SQL COPY(7) command, but instead of the server reading or

writing the specified file, psql reads or writes the file and routes the data

between the server and the local file system. This means that file

accessibility and privileges are those of the local user, not the server, and

no SQL superuser privileges are required.

When program is specified, command is executed by psql and

the data passed from or to command is routed between the server and

the client. Again, the execution privileges are those of the local user, not

the server, and no SQL superuser privileges are required.

For \copy … from stdin, data rows are read from the same source

that issued the command, continuing until \. is read or the stream reaches

EOF. This option is useful for populating tables in-line within a SQL script

file. For \copy … to stdout, output is sent to the same place as psql

command output, and the COPY count command status is not printed

(since it might be confused with a data row). To read/write psql’s standard

input or output regardless of the current command source or \o option, write

from pstdin or to pstdout.

The syntax of this command is similar to that of the SQL

COPY(7) command. All options other than the data source/destination

are as specified for COPY(7). Because of this, special parsing rules

apply to the \copy meta-command. Unlike most other meta-commands, the

entire remainder of the line is always taken to be the arguments of

\copy, and neither variable interpolation nor backquote expansion are

performed in the arguments.

Tip

This operation is not as efficient as the SQL COPY command because all

data must pass through the client/server connection. For large amounts of data

the SQL command might be preferable.

\copyright

Shows the copyright and distribution terms of

PostgreSQL.

\crosstabview [ colV [ colH [ colD [

sortcolH ] ] ] ]

Executes the current query buffer (like \g) and shows the

results in a crosstab grid. The query must return at least three columns. The

output column identified by colV becomes a vertical header and the

output column identified by colH becomes a horizontal header.

colD identifies the output column to display within the grid.

sortcolH identifies an optional sort column for the horizontal header.

Each column specification can be a column number (starting at 1)

or a column name. The usual SQL case folding and quoting rules apply to

column names. If omitted, colV is taken as column 1 and colH

as column 2. colH must differ from colV. If colD is not

specified, then there must be exactly three columns in the query result, and

the column that is neither colV nor colH is taken to be

colD.

The vertical header, displayed as the leftmost column, contains

the values found in column colV, in the same order as in the query

results, but with duplicates removed.

The horizontal header, displayed as the first row, contains the

values found in column colH, with duplicates removed. By default,

these appear in the same order as in the query results. But if the optional

sortcolH argument is given, it identifies a column whose values must

be integer numbers, and the values from colH will appear in the

horizontal header sorted according to the corresponding sortcolH

values.

Inside the crosstab grid, for each distinct value x of colH

and each distinct value y of colV, the cell located at the

intersection (x,y) contains the value of the colD column in the query result

row for which the value of colH is x and the value of colV is

y. If there is no such row, the cell is empty. If there are multiple such

rows, an error is reported.

\d[S+] [ pattern ]

For each relation (table, view, materialized view, index,

sequence, or foreign table) or composite type matching the pattern,

show all columns, their types, the tablespace (if not the default) and any

special attributes such as NOT NULL or defaults. Associated indexes,

constraints, rules, and triggers are also shown. For foreign tables, the

associated foreign server is shown as well. (“Matching the

pattern” is defined in Patterns below.)

For some types of relation, \d shows additional information for

each column: column values for sequences, indexed expressions for indexes,

and foreign data wrapper options for foreign tables.

The command form \d+ is identical, except that more information is

displayed: any comments associated with the columns of the table are shown,

as is the presence of OIDs in the table, the view definition if the relation

is a view, a non-default replica identity setting.

By default, only user-created objects are shown; supply a pattern

or the S modifier to include system objects.

Note

If \d is used without a pattern argument, it is equivalent to

\dtvmsE which will show a list of all visible tables, views,

materialized views, sequences and foreign tables. This is purely a convenience

measure.

\da[S] [ pattern ]

Lists aggregate functions, together with their return

type and the data types they operate on. If pattern is specified, only

aggregates whose names match the pattern are shown. By default, only

user-created objects are shown; supply a pattern or the S modifier to include

system objects.

\dA[+] [ pattern ]

Lists access methods. If pattern is specified,

only access methods whose names match the pattern are shown. If + is appended

to the command name, each access method is listed with its associated handler

function and description.

\db[+] [ pattern ]

Lists tablespaces. If pattern is specified, only

tablespaces whose names match the pattern are shown. If + is appended to the

command name, each tablespace is listed with its associated options, on-disk

size, permissions and description.

\dc[S+] [ pattern ]

Lists conversions between character-set encodings. If

pattern is specified, only conversions whose names match the pattern

are listed. By default, only user-created objects are shown; supply a pattern

or the S modifier to include system objects. If + is appended to the command

name, each object is listed with its associated description.

\dC[+] [ pattern ]

Lists type casts. If pattern is specified, only

casts whose source or target types match the pattern are listed. If + is

appended to the command name, each object is listed with its associated

description.

\dd[S] [ pattern ]

Shows the descriptions of objects of type constraint,

operator class, operator family, rule, and trigger. All other comments may be

viewed by the respective backslash commands for those object types.

\dd displays descriptions for objects matching the pattern,

or of visible objects of the appropriate type if no argument is given. But

in either case, only objects that have a description are listed. By default,

only user-created objects are shown; supply a pattern or the S modifier to

include system objects.

Descriptions for objects can be created with the COMMENT(7)

SQL command.

\dD[S+] [ pattern ]

Lists domains. If pattern is specified, only

domains whose names match the pattern are shown. By default, only user-created

objects are shown; supply a pattern or the S modifier to include system

objects. If + is appended to the command name, each object is listed with its

associated permissions and description.

\ddp [ pattern ]

Lists default access privilege settings. An entry is

shown for each role (and schema, if applicable) for which the default

privilege settings have been changed from the built-in defaults. If

pattern is specified, only entries whose role name or schema name

matches the pattern are listed.

The ALTER DEFAULT PRIVILEGES (ALTER_DEFAULT_PRIVILEGES(7))

command is used to set default access privileges. The meaning of the

privilege display is explained under GRANT(7).

\dE[S+] [ pattern ]

\di[S+] [ pattern ]

\dm[S+] [ pattern ]

\ds[S+] [ pattern ]

\dt[S+] [ pattern ]

\dv[S+] [ pattern ]

In this group of commands, the letters E, i, m, s, t, and

v stand for foreign table, index, materialized view, sequence, table, and

view, respectively. You can specify any or all of these letters, in any order,

to obtain a listing of objects of these types. For example, \dit lists indexes

and tables. If + is appended to the command name, each object is listed with

its physical size on disk and its associated description, if any. If

pattern is specified, only objects whose names match the pattern are

listed. By default, only user-created objects are shown; supply a pattern or

the S modifier to include system objects.

\des[+] [ pattern ]

Lists foreign servers (mnemonic: “external

servers”). If pattern is specified, only those servers whose

name matches the pattern are listed. If the form \des+ is used, a full

description of each server is shown, including the server’s ACL, type,

version, options, and description.

\det[+] [ pattern ]

Lists foreign tables (mnemonic: “external

tables”). If pattern is specified, only entries whose table name

or schema name matches the pattern are listed. If the form \det+ is used,

generic options and the foreign table description are also displayed.

\deu[+] [ pattern ]

Lists user mappings (mnemonic: “external

users”). If pattern is specified, only those mappings whose user

names match the pattern are listed. If the form \deu+ is used, additional

information about each mapping is shown.

Caution

\deu+ might also display the user name and password of the remote user, so care

should be taken not to disclose them.

\dew[+] [ pattern ]

Lists foreign-data wrappers (mnemonic: “external

wrappers”). If pattern is specified, only those foreign-data

wrappers whose name matches the pattern are listed. If the form \dew+ is used,

the ACL, options, and description of the foreign-data wrapper are also

shown.

\df[antwS+] [ pattern ]

Lists functions, together with their result data types,

argument data types, and function types, which are classified as

“agg” (aggregate), “normal”,

“trigger”, or “window”. To display only functions

of specific type(s), add the corresponding letters a, n, t, or w to the

command. If pattern is specified, only functions whose names match the

pattern are shown. By default, only user-created objects are shown; supply a

pattern or the S modifier to include system objects. If the form \df+ is used,

additional information about each function is shown, including volatility,

parallel safety, owner, security classification, access privileges, language,

source code and description.

Tip

To look up functions taking arguments or returning values of a specific data

type, use your pager’s search capability to scroll through the \df output.

\dF[+] [ pattern ]

Lists text search configurations. If pattern is

specified, only configurations whose names match the pattern are shown. If the

form \dF+ is used, a full description of each configuration is shown,

including the underlying text search parser and the dictionary list for each

parser token type.

\dFd[+] [ pattern ]

Lists text search dictionaries. If pattern is

specified, only dictionaries whose names match the pattern are shown. If the

form \dFd+ is used, additional information is shown about each selected

dictionary, including the underlying text search template and the option

values.

\dFp[+] [ pattern ]

Lists text search parsers. If pattern is

specified, only parsers whose names match the pattern are shown. If the form

\dFp+ is used, a full description of each parser is shown, including the

underlying functions and the list of recognized token types.

\dFt[+] [ pattern ]

Lists text search templates. If pattern is

specified, only templates whose names match the pattern are shown. If the form

\dFt+ is used, additional information is shown about each template, including

the underlying function names.

\dg[S+] [ pattern ]

Lists database roles. (Since the concepts of

“users” and “groups” have been unified into

“roles”, this command is now equivalent to \du.) By default,

only user-created roles are shown; supply the S modifier to include system

roles. If pattern is specified, only those roles whose names match the

pattern are listed. If the form \dg+ is used, additional information is shown

about each role; currently this adds the comment for each role.

\dl

This is an alias for \lo_list, which shows a list

of large objects.

\dL[S+] [ pattern ]

Lists procedural languages. If pattern is

specified, only languages whose names match the pattern are listed. By

default, only user-created languages are shown; supply the S modifier to

include system objects. If + is appended to the command name, each language is

listed with its call handler, validator, access privileges, and whether it is

a system object.

\dn[S+] [ pattern ]

Lists schemas (namespaces). If pattern is

specified, only schemas whose names match the pattern are listed. By default,

only user-created objects are shown; supply a pattern or the S modifier to

include system objects. If + is appended to the command name, each object is

listed with its associated permissions and description, if any.

\do[S+] [ pattern ]

Lists operators with their operand and result types. If

pattern is specified, only operators whose names match the pattern are

listed. By default, only user-created objects are shown; supply a pattern or

the S modifier to include system objects. If + is appended to the command

name, additional information about each operator is shown, currently just the

name of the underlying function.

\dO[S+] [ pattern ]

Lists collations. If pattern is specified, only

collations whose names match the pattern are listed. By default, only

user-created objects are shown; supply a pattern or the S modifier to include

system objects. If + is appended to the command name, each collation is listed

with its associated description, if any. Note that only collations usable with

the current database’s encoding are shown, so the results may vary in

different databases of the same installation.

\dp [ pattern ]

Lists tables, views and sequences with their associated

access privileges. If pattern is specified, only tables, views and

sequences whose names match the pattern are listed.

The GRANT(7) and REVOKE(7) commands are used to set

access privileges. The meaning of the privilege display is explained under

GRANT(7).

\drds [ role-pattern [ database-pattern ] ]

Lists defined configuration settings. These settings can

be role-specific, database-specific, or both. role-pattern and

database-pattern are used to select specific roles and databases to

list, respectively. If omitted, or if * is specified, all settings are listed,

including those not role-specific or database-specific, respectively.

The ALTER ROLE (ALTER_ROLE(7)) and ALTER DATABASE

(ALTER_DATABASE(7)) commands are used to define per-role and

per-database configuration settings.

\dRp[+] [ pattern ]

Lists replication publications. If pattern is

specified, only those publications whose names match the pattern are listed.

If + is appended to the command name, the tables associated with each

publication are shown as well.

\dRs[+] [ pattern ]

Lists replication subscriptions. If pattern is

specified, only those subscriptions whose names match the pattern are listed.

If + is appended to the command name, additional properties of the

subscriptions are shown.

\dT[S+] [ pattern ]

Lists data types. If pattern is specified, only

types whose names match the pattern are listed. If + is appended to the

command name, each type is listed with its internal name and size, its allowed

values if it is an enum type, and its associated permissions. By default, only

user-created objects are shown; supply a pattern or the S modifier to include

system objects.

\du[S+] [ pattern ]

Lists database roles. (Since the concepts of

“users” and “groups” have been unified into

“roles”, this command is now equivalent to \dg.) By default,

only user-created roles are shown; supply the S modifier to include system

roles. If pattern is specified, only those roles whose names match the

pattern are listed. If the form \du+ is used, additional information is shown

about each role; currently this adds the comment for each role.

\dx[+] [ pattern ]

Lists installed extensions. If pattern is

specified, only those extensions whose names match the pattern are listed. If

the form \dx+ is used, all the objects belonging to each matching extension

are listed.

\dy[+] [ pattern ]

Lists event triggers. If pattern is specified,

only those event triggers whose names match the pattern are listed. If + is

appended to the command name, each object is listed with its associated

description.

\e or \edit [ filename ] [ line_number ]

If filename is specified, the file is edited;

after the editor exits, the file’s content is copied into the current query

buffer. If no filename is given, the current query buffer is copied to

a temporary file which is then edited in the same fashion. Or, if the current

query buffer is empty, the most recently executed query is copied to a

temporary file and edited in the same fashion.

The new contents of the query buffer are then re-parsed according

to the normal rules of psql, treating the whole buffer as a single line. Any

complete queries are immediately executed; that is, if the query buffer

contains or ends with a semicolon, everything up to that point is executed.

Whatever remains will wait in the query buffer; type semicolon or \g to send

it, or \r to cancel it by clearing the query buffer. Treating the buffer as

a single line primarily affects meta-commands: whatever is in the buffer

after a meta-command will be taken as argument(s) to the meta-command, even

if it spans multiple lines. (Thus you cannot make meta-command-using scripts

this way. Use \i for that.)

If a line number is specified, psql will position the cursor on

the specified line of the file or query buffer. Note that if a single

all-digits argument is given, psql assumes it is a line number, not a file

name.

Tip

See under ENVIRONMENT for how to configure and customize your editor.

\echo text [ … ]

Prints the arguments to the standard output, separated by

one space and followed by a newline. This can be useful to intersperse

information in the output of scripts. For example:

=> \echo `date` Tue Oct 26 21:40:57 CEST 1999

If the first argument is an unquoted -n the trailing newline is

not written.

Tip

If you use the \o command to redirect your query output you might wish to

use \qecho instead of this command.

\ef [ function_description [ line_number ] ]

This command fetches and edits the definition of the

named function, in the form of a CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION command.

Editing is done in the same way as for \edit. After the editor exits, the

updated command waits in the query buffer; type semicolon or \g to send it, or

\r to cancel.

The target function can be specified by name alone, or by name and

arguments, for example foo(integer, text). The argument types must be given

if there is more than one function of the same name.

If no function is specified, a blank CREATE FUNCTION

template is presented for editing.

If a line number is specified, psql will position the cursor on

the specified line of the function body. (Note that the function body

typically does not begin on the first line of the file.)

Unlike most other meta-commands, the entire remainder of the line

is always taken to be the argument(s) of \ef, and neither variable

interpolation nor backquote expansion are performed in the arguments.

Tip

See under ENVIRONMENT for how to configure and customize your editor.

\encoding [ encoding ]

Sets the client character set encoding. Without an

argument, this command shows the current encoding.

\errverbose

Repeats the most recent server error message at maximum

verbosity, as though VERBOSITY were set to verbose and

SHOW_CONTEXT were set to always.

\ev [ view_name [ line_number ] ]

This command fetches and edits the definition of the

named view, in the form of a CREATE OR REPLACE VIEW command. Editing is

done in the same way as for \edit. After the editor exits, the updated command

waits in the query buffer; type semicolon or \g to send it, or \r to cancel.

If no view is specified, a blank CREATE VIEW template is

presented for editing.

If a line number is specified, psql will position the cursor on

the specified line of the view definition.

Unlike most other meta-commands, the entire remainder of the line

is always taken to be the argument(s) of \ev, and neither variable

interpolation nor backquote expansion are performed in the arguments.

\f [ string ]

Sets the field separator for unaligned query output. The

default is the vertical bar (|). It is equivalent to \pset

fieldsep.

\g [ filename ]

\g [ |command ]

Sends the current query buffer to the server for

execution. If an argument is given, the query’s output is written to the named

file or piped to the given shell command, instead of displaying it as usual.

The file or command is written to only if the query successfully returns zero

or more tuples, not if the query fails or is a non-data-returning SQL command.

If the current query buffer is empty, the most recently sent query

is re-executed instead. Except for that behavior, \g without an argument is

essentially equivalent to a semicolon. A \g with argument is a

“one-shot” alternative to the \o command.

If the argument begins with |, then the entire remainder of the

line is taken to be the command to execute, and neither variable

interpolation nor backquote expansion are performed in it. The rest of the

line is simply passed literally to the shell.

\gexec

Sends the current query buffer to the server, then treats

each column of each row of the query’s output (if any) as a SQL statement to

be executed. For example, to create an index on each column of my_table:

=> SELECT format('create index on my_table(%I)', attname)

-> FROM pg_attribute

-> WHERE attrelid = 'my_table'::regclass AND attnum > 0

-> ORDER BY attnum

-> \gexec

CREATE INDEX

CREATE INDEX

CREATE INDEX

CREATE INDEX

The generated queries are executed in the order in which the rows

are returned, and left-to-right within each row if there is more than one

column. NULL fields are ignored. The generated queries are sent literally to

the server for processing, so they cannot be psql meta-commands nor contain

psql variable references. If any individual query fails, execution of the

remaining queries continues unless ON_ERROR_STOP is set. Execution of

each query is subject to ECHO processing. (Setting ECHO to all

or queries is often advisable when using \gexec.) Query logging,

single-step mode, timing, and other query execution features apply to each

generated query as well.

If the current query buffer is empty, the most recently sent query

is re-executed instead.

\gset [ prefix ]

Sends the current query buffer to the server and stores

the query’s output into psql variables (see Variables). The query to be

executed must return exactly one row. Each column of the row is stored into a

separate variable, named the same as the column. For example:

=> SELECT 'hello' AS var1, 10 AS var2 -> \gset => \echo :var1 :var2 hello 10

If you specify a prefix, that string is prepended to the

query’s column names to create the variable names to use:

=> SELECT 'hello' AS var1, 10 AS var2 -> \gset result_ => \echo :result_var1 :result_var2 hello 10

If a column result is NULL, the corresponding variable is unset

rather than being set.

If the query fails or does not return one row, no variables are

changed.

If the current query buffer is empty, the most recently sent query

is re-executed instead.

\gx [ filename ]

\gx [ |command ]

\gx is equivalent to \g, but forces expanded output mode

for this query. See \x.

\h or \help [ command ]

Gives syntax help on the specified SQL command. If

command is not specified, then psql will list all the commands for

which syntax help is available. If command is an asterisk (*), then

syntax help on all SQL commands is shown.

Unlike most other meta-commands, the entire remainder of the line

is always taken to be the argument(s) of \help, and neither variable

interpolation nor backquote expansion are performed in the arguments.

Note

To simplify typing, commands that consists of several words do not have to be

quoted. Thus it is fine to type \help alter table.

\H or \html

Turns on HTML query output format. If the HTML format is

already on, it is switched back to the default aligned text format. This

command is for compatibility and convenience, but see \pset about

setting other output options.

\i or \include filename

Reads input from the file filename and executes it

as though it had been typed on the keyboard.

If filename is — (hyphen), then standard input is read

until an EOF indication or \q meta-command. This can be used to

intersperse interactive input with input from files. Note that Readline

behavior will be used only if it is active at the outermost level.

Note

If you want to see the lines on the screen as they are read you must set the

variable ECHO to all.

\if expression

\elif expression

\else

\endif

This group of commands implements nestable conditional

blocks. A conditional block must begin with an \if and end with an

\endif. In between there may be any number of \elif clauses,

which may optionally be followed by a single \else clause. Ordinary

queries and other types of backslash commands may (and usually do) appear

between the commands forming a conditional block.

The \if and \elif commands read their argument(s)

and evaluate them as a boolean expression. If the expression yields true

then processing continues normally; otherwise, lines are skipped until a

matching \elif, \else, or \endif is reached. Once an