Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4) is the fourth version of the Internet Protocol (IP). It is one of the core protocols of standards-based internetworking methods in the Internet and other packet-switched networks. IPv4 was the first version deployed for production on SATNET in 1982 and on the ARPANET in January 1983. It is still used to route most Internet traffic today,[1] even with the ongoing deployment of Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6),[2] its successor.

| Protocol stack | |

IPv4 packet |

|

| Abbreviation | IPv4 |

|---|---|

| Purpose | internetworking protocol |

| Developer(s) | DARPA |

| Introduction | 1981; 42 years ago |

| Influenced | IPv6 |

| OSI layer | Network layer |

| RFC(s) | 791 |

IPv4 uses a 32-bit address space which provides 4,294,967,296 (232) unique addresses, but large blocks are reserved for special networking purposes.[3][4]

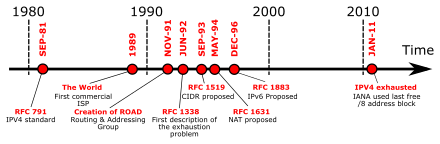

History

Edit

Internet Protocol version 4 is described in IETF publication RFC 791 (September 1981), replacing an earlier definition of January 1980 (RFC 760). In March 1982, the US Department of Defense decided on the Internet Protocol Suite (TCP/IP) as the standard for all military computer networking.[5]

Purpose

Edit

The Internet Protocol is the protocol that defines and enables internetworking at the internet layer of the Internet Protocol Suite. In essence it forms the Internet. It uses a logical addressing system and performs routing, which is the forwarding of packets from a source host to the next router that is one hop closer to the intended destination host on another network.

IPv4 is a connectionless protocol, and operates on a best-effort delivery model, in that it does not guarantee delivery, nor does it assure proper sequencing or avoidance of duplicate delivery. These aspects, including data integrity, are addressed by an upper layer transport protocol, such as the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP).

Addressing

Edit

For broader coverage of this topic, see IP address.

IPv4 uses 32-bit addresses which limits the address space to 4294967296 (232) addresses.

IPv4 reserves special address blocks for private networks (~18 million addresses) and multicast addresses (~270 million addresses).

Address representations

Edit

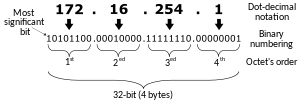

IPv4 addresses may be represented in any notation expressing a 32-bit integer value. They are most often written in dot-decimal notation, which consists of four octets of the address expressed individually in decimal numbers and separated by periods.

For example, the quad-dotted IP address 192.0.2.235 represents the 32-bit decimal number 3221226219, which in hexadecimal format is 0xC00002EB.

CIDR notation combines the address with its routing prefix in a compact format, in which the address is followed by a slash character (/) and the count of leading consecutive 1 bits in the routing prefix (subnet mask).

Other address representations were in common use when classful networking was practiced. For example, the loopback address 127.0.0.1 was commonly written as 127.1, given that it belongs to a class-A network with eight bits for the network mask and 24 bits for the host number. When fewer than four numbers were specified in the address in dotted notation, the last value was treated as an integer of as many bytes as are required to fill out the address to four octets. Thus, the address 127.65530 is equivalent to 127.0.255.250.

Allocation

Edit

In the original design of IPv4, an IP address was divided into two parts: the network identifier was the most significant octet of the address, and the host identifier was the rest of the address. The latter was also called the rest field. This structure permitted a maximum of 256 network identifiers, which was quickly found to be inadequate.

To overcome this limit, the most-significant address octet was redefined in 1981 to create network classes, in a system which later became known as classful networking. The revised system defined five classes. Classes A, B, and C had different bit lengths for network identification. The rest of the address was used as previously to identify a host within a network. Because of the different sizes of fields in different classes, each network class had a different capacity for addressing hosts. In addition to the three classes for addressing hosts, Class D was defined for multicast addressing and Class E was reserved for future applications.

Dividing existing classful networks into subnets began in 1985 with the publication of RFC 950. This division was made more flexible with the introduction of variable-length subnet masks (VLSM) in RFC 1109 in 1987. In 1993, based on this work, RFC 1517 introduced Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR),[6] which expressed the number of bits (from the most significant) as, for instance, /24, and the class-based scheme was dubbed classful, by contrast. CIDR was designed to permit repartitioning of any address space so that smaller or larger blocks of addresses could be allocated to users. The hierarchical structure created by CIDR is managed by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) and the regional Internet registries (RIRs). Each RIR maintains a publicly searchable WHOIS database that provides information about IP address assignments.

Special-use addresses

Edit

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and IANA have restricted from general use various reserved IP addresses for special purposes.[7] Notably these addresses are used for multicast traffic and to provide addressing space for unrestricted uses on private networks.

-

Special address blocks

Address block Address range Number of addresses Scope Description 0.0.0.0/8 0.0.0.0–0.255.255.255 16777216 Software Current (local, «this») network[7] 10.0.0.0/8 10.0.0.0–10.255.255.255 16777216 Private network Used for local communications within a private network.[8] 100.64.0.0/10 100.64.0.0–100.127.255.255 4194304 Private network Shared address space[9] for communications between a service provider and its subscribers when using a carrier-grade NAT. 127.0.0.0/8 127.0.0.0–127.255.255.255 16777216 Host Used for loopback addresses to the local host.[7] 169.254.0.0/16 169.254.0.0–169.254.255.255 65536 Subnet Used for link-local addresses[10] between two hosts on a single link when no IP address is otherwise specified, such as would have normally been retrieved from a DHCP server. 172.16.0.0/12 172.16.0.0–172.31.255.255 1048576 Private network Used for local communications within a private network.[8] 192.0.0.0/24 192.0.0.0–192.0.0.255 256 Private network IETF Protocol Assignments, DS-Lite (/29).[7] 192.0.2.0/24 192.0.2.0–192.0.2.255 256 Documentation Assigned as TEST-NET-1, documentation and examples.[11] 192.88.99.0/24 192.88.99.0–192.88.99.255 256 Internet Reserved.[12] Formerly used for IPv6 to IPv4 relay[13] (included IPv6 address block 2002::/16). 192.168.0.0/16 192.168.0.0–192.168.255.255 65536 Private network Used for local communications within a private network.[8] 198.18.0.0/15 198.18.0.0–198.19.255.255 131072 Private network Used for benchmark testing of inter-network communications between two separate subnets.[14] 198.51.100.0/24 198.51.100.0–198.51.100.255 256 Documentation Assigned as TEST-NET-2, documentation and examples.[11] 203.0.113.0/24 203.0.113.0–203.0.113.255 256 Documentation Assigned as TEST-NET-3, documentation and examples.[11] 224.0.0.0/4 224.0.0.0–239.255.255.255 268435456 Internet In use for IP multicast.[15] (Former Class D network.) 233.252.0.0/24 233.252.0.0-233.252.0.255 256 Documentation Assigned as MCAST-TEST-NET, documentation and examples.[15][16] 240.0.0.0/4 240.0.0.0–255.255.255.254 268435455 Internet Reserved for future use.[17] (Former Class E network.) 255.255.255.255/32 255.255.255.255 1 Subnet Reserved for the «limited broadcast» destination address.[7]

Private networks

Edit

Of the approximately four billion addresses defined in IPv4, about 18 million addresses in three ranges are reserved for use in private networks. Packets addresses in these ranges are not routable in the public Internet; they are ignored by all public routers. Therefore, private hosts cannot directly communicate with public networks, but require network address translation at a routing gateway for this purpose.

-

Reserved private IPv4 network ranges[8]

Name CIDR block Address range Number of addresses Classful description 24-bit block 10.0.0.0/8 10.0.0.0 – 10.255.255.255 16777216 Single Class A. 20-bit block 172.16.0.0/12 172.16.0.0 – 172.31.255.255 1048576 Contiguous range of 16 Class B blocks. 16-bit block 192.168.0.0/16 192.168.0.0 – 192.168.255.255 65536 Contiguous range of 256 Class C blocks.

Since two private networks, e.g., two branch offices, cannot directly interoperate via the public Internet, the two networks must be bridged across the Internet via a virtual private network (VPN) or an IP tunnel, which encapsulates packets, including their headers containing the private addresses, in a protocol layer during transmission across the public network. Additionally, encapsulated packets may be encrypted for transmission across public networks to secure the data.

Link-local addressing

Edit

RFC 3927 defines the special address block 169.254.0.0/16 for link-local addressing. These addresses are only valid on the link (such as a local network segment or point-to-point connection) directly connected to a host that uses them. These addresses are not routable. Like private addresses, these addresses cannot be the source or destination of packets traversing the internet. These addresses are primarily used for address autoconfiguration (Zeroconf) when a host cannot obtain an IP address from a DHCP server or other internal configuration methods.

When the address block was reserved, no standards existed for address autoconfiguration. Microsoft created an implementation called Automatic Private IP Addressing (APIPA), which was deployed on millions of machines and became a de facto standard. Many years later, in May 2005, the IETF defined a formal standard in RFC 3927, entitled Dynamic Configuration of IPv4 Link-Local Addresses.

Loopback

Edit

The class A network 127.0.0.0 (classless network 127.0.0.0/8) is reserved for loopback. IP packets whose source addresses belong to this network should never appear outside a host. Packets received on a non-loopback interface with a loopback source or destination address must be dropped.

First and last subnet addresses

Edit

The first address in a subnet is used to identify the subnet itself. In this address all host bits are 0. To avoid ambiguity in representation, this address is reserved.[18] The last address has all host bits set to 1. It is used as a local broadcast address for sending messages to all devices on the subnet simultaneously. For networks of size /24 or larger, the broadcast address always ends in 255.

For example, in the subnet 192.168.5.0/24 (subnet mask 255.255.255.0) the identifier 192.168.5.0 is used to refer to the entire subnet. The broadcast address of the network is 192.168.5.255.

| Type | Binary form | Dot-decimal notation |

|---|---|---|

| Network space | 11000000.10101000.00000101.00000000

|

192.168.5.0 |

| Broadcast address | 11000000.10101000.00000101.11111111

|

192.168.5.255 |

| In red, is shown the host part of the IP address; the other part is the network prefix. The host gets inverted (logical NOT), but the network prefix remains intact. |

However, this does not mean that every address ending in 0 or 255 cannot be used as a host address. For example, in the /16 subnet 192.168.0.0/255.255.0.0, which is equivalent to the address range 192.168.0.0–192.168.255.255, the broadcast address is 192.168.255.255. One can use the following addresses for hosts, even though they end with 255: 192.168.1.255, 192.168.2.255, etc. Also, 192.168.0.0 is the network identifier and must not be assigned to an interface.[19]: 31 The addresses 192.168.1.0, 192.168.2.0, etc., may be assigned, despite ending with 0.

In the past, conflict between network addresses and broadcast addresses arose because some software used non-standard broadcast addresses with zeros instead of ones.[19]: 66

In networks smaller than /24, broadcast addresses do not necessarily end with 255. For example, a CIDR subnet 203.0.113.16/28 has the broadcast address 203.0.113.31.

| Type | Binary form | Dot-decimal notation |

|---|---|---|

| Network space | 11001011.00000000.01110001.00010000

|

203.0.113.16 |

| Broadcast address | 11001011.00000000.01110001.00011111

|

203.0.113.31 |

| In red, is shown the host part of the IP address; the other part is the network prefix. The host gets inverted (logical NOT), but the network prefix remains intact. |

As a special case, a /31 network has capacity for just two hosts. These networks are typically used for point-to-point connections. There is no network identifier or broadcast address for these networks.[20]

Address resolution

Edit

Hosts on the Internet are usually known by names, e.g., www.example.com, not primarily by their IP address, which is used for routing and network interface identification. The use of domain names requires translating, called resolving, them to addresses and vice versa. This is analogous to looking up a phone number in a phone book using the recipient’s name.

The translation between addresses and domain names is performed by the Domain Name System (DNS), a hierarchical, distributed naming system that allows for the subdelegation of namespaces to other DNS servers.

Unnumbered interface

Edit

A unnumbered point-to-point (PtP) link, also called a transit link, is a link that doesn’t have an IP network or subnet number associated with it, but still has an IP address. First introduced in 1993,[21][22][23][24] Phil Karn from Qualcomm is credited as the original designer.

The purpose of a transit link is to route datagrams. They are used to free IP addresses from a scarce IP address space or to reduce the management of assigning IP and configuration of interfaces. Previously, every link needed to dedicate a /31 or /30 subnet using 2 or 4 IP addresses per point-to-point link. When a link is unnumbered, a router-id is used, a single IP address borrowed from a defined (normally a loopback) interface. The same router-id can be used on multiple interfaces.

One of the disadvantages of unnumbered interfaces is that it is harder to do remote testing and management.

Address space exhaustion

Edit

In the 1980s, it became apparent that the pool of available IPv4 addresses was depleting at a rate that was not initially anticipated in the original design of the network.[25] The main market forces that accelerated address depletion included the rapidly growing number of Internet users, who increasingly used mobile computing devices, such as laptop computers, personal digital assistants (PDAs), and smart phones with IP data services. In addition, high-speed Internet access was based on always-on devices. The threat of exhaustion motivated the introduction of a number of remedial technologies, such as:

- Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR), for smaller ISP allocations

- Unnumbered interface, removed the need on transit links.

- network address translation (NAT), removed the need for end-to-end principle.

By the mid-1990s, NAT was used pervasively in network access provider systems, along with strict usage-based allocation policies at the regional and local Internet registries.

The primary address pool of the Internet, maintained by IANA, was exhausted on 3 February 2011, when the last five blocks were allocated to the five RIRs.[26][27] APNIC was the first RIR to exhaust its regional pool on 15 April 2011, except for a small amount of address space reserved for the transition technologies to IPv6, which is to be allocated under a restricted policy.[28]

The long-term solution to address exhaustion was the 1998 specification of a new version of the Internet Protocol, IPv6.[29] It provides a vastly increased address space, but also allows improved route aggregation across the Internet, and offers large subnetwork allocations of a minimum of 264 host addresses to end users. However, IPv4 is not directly interoperable with IPv6, so that IPv4-only hosts cannot directly communicate with IPv6-only hosts. With the phase-out of the 6bone experimental network starting in 2004, permanent formal deployment of IPv6 commenced in 2006.[30] Completion of IPv6 deployment is expected to take considerable time,[31] so that intermediate transition technologies are necessary to permit hosts to participate in the Internet using both versions of the protocol.

Packet structure

Edit

An IP packet consists of a header section and a data section. An IP packet has no data checksum or any other footer after the data section.

Typically the link layer encapsulates IP packets in frames with a CRC footer that detects most errors, many transport-layer protocols carried by IP also have their own error checking.[32]

Edit

The IPv4 packet header consists of 14 fields, of which 13 are required. The 14th field is optional and aptly named: options. The fields in the header are packed with the most significant byte first (network byte order), and for the diagram and discussion, the most significant bits are considered to come first (MSB 0 bit numbering). The most significant bit is numbered 0, so the version field is actually found in the four most significant bits of the first byte, for example.

| Offsets | Octet | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octet | Bit | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

| 0 | 0 | Version | IHL | DSCP | ECN | Total Length | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 32 | Identification | Flags | Fragment Offset | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | 64 | Time To Live | Protocol | Header Checksum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 96 | Source IP Address | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | 128 | Destination IP Address | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 160 | Options (if IHL > 5) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 56 | 448 |

- Version

- The first header field in an IP packet is the four-bit version field. For IPv4, this is always equal to 4.

- Internet Header Length (IHL)

- The IPv4 header is variable in size due to the optional 14th field (options). The IHL field contains the size of the IPv4 header; it has 4 bits that specify the number of 32-bit words in the header. The minimum value for this field is 5,[33] which indicates a length of 5 × 32 bits = 160 bits = 20 bytes. As a 4-bit field, the maximum value is 15; this means that the maximum size of the IPv4 header is 15 × 32 bits = 480 bits = 60 bytes.

- Differentiated Services Code Point (DSCP)

- Originally defined as the type of service (ToS), this field specifies differentiated services (DiffServ).[34] Real-time data streaming makes use of the DSCP field. An example is Voice over IP (VoIP), which is used for interactive voice services.

- Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN)

- This field allows end-to-end notification of network congestion without dropping packets.[35] ECN is an optional feature available when both endpoints support it and effective when also supported by the underlying network.

- Total Length

- This 16-bit field defines the entire packet size in bytes, including header and data. The minimum size is 20 bytes (header without data) and the maximum is 65,535 bytes. All hosts are required to be able to reassemble datagrams of size up to 576 bytes, but most modern hosts handle much larger packets. Links may impose further restrictions on the packet size, in which case datagrams must be fragmented. Fragmentation in IPv4 is performed in either the sending host or in routers. Reassembly is performed at the receiving host.

- Identification

- This field is an identification field and is primarily used for uniquely identifying the group of fragments of a single IP datagram. Some experimental work has suggested using the ID field for other purposes, such as for adding packet-tracing information to help trace datagrams with spoofed source addresses,[36] but any such use is now prohibited.[37]

- Flags

- A three-bit field follows and is used to control or identify fragments. They are (in order, from most significant to least significant):

- bit 0: Reserved; must be zero.[a]

- bit 1: Don’t Fragment (DF)

- bit 2: More Fragments (MF)

- If the DF flag is set, and fragmentation is required to route the packet, then the packet is dropped. This can be used when sending packets to a host that does not have resources to perform reassembly of fragments. It can also be used for path MTU discovery, either automatically by the host IP software, or manually using diagnostic tools such as ping or traceroute.

- For unfragmented packets, the MF flag is cleared. For fragmented packets, all fragments except the last have the MF flag set. The last fragment has a non-zero Fragment Offset field, differentiating it from an unfragmented packet.

- Fragment offset

- This field specifies the offset of a particular fragment relative to the beginning of the original unfragmented IP datagram. The fragmentation offset value for the first fragment is always 0. The field is 13 bits wide, so that the offset can be from 0 to 8191 (from (20 – 1) to (213 – 1)). Fragments are specified in units of 8 bytes, which is why fragment length must be a multiple of 8.[38] Therefore, the 13-bit field allows a maximum offset of (213 – 1) × 8 = 65,528 bytes, with the header length included (65,528 + 20 = 65,548 bytes), supporting fragmentation of packets exceeding the maximum IP length of 65,535 bytes.

- Time to live (TTL)

- An eight-bit time to live field limits a datagram’s lifetime to prevent network failure in the event of a routing loop. It is specified in seconds, but time intervals less than 1 second are rounded up to 1. In practice, the field is used as a hop count—when the datagram arrives at a router, the router decrements the TTL field by one. When the TTL field hits zero, the router discards the packet and typically sends an ICMP time exceeded message to the sender.

- The program traceroute sends messages with adjusted TTL values and uses these ICMP time exceeded messages to identify the routers traversed by packets from the source to the destination.

- Protocol

- This field defines the protocol used in the data portion of the IP datagram. IANA maintains a list of IP protocol numbers.[39]

- Header checksum

- The 16-bit IPv4 header checksum field is used for error-checking of the header. When a packet arrives at a router, the router calculates the checksum of the header and compares it to the checksum field. If the values do not match, the router discards the packet. Errors in the data field must be handled by the encapsulated protocol. Both UDP and TCP have separate checksums that apply to their data.

- When a packet arrives at a router, the router decreases the TTL field in the header. Consequently, the router must calculate a new header checksum.

- The checksum field is the 16 bit one’s complement of the one’s complement sum of all 16 bit words in the header. For purposes of computing the checksum, the value of the checksum field is zero.

- Source address

- This 32-bit field is the IPv4 address of the sender of the packet. It may be changed in transit by network address translation (NAT).

- Destination address

- This 32-bit field is the IPv4 address of the receiver of the packet. It may be affected by NAT.

- Options

- The options field is not often used. Packets containing some options may be considered as dangerous by some routers and be blocked.[40] The value in the IHL field must include sufficient extra 32-bit words to hold all options and any padding needed to ensure that the header contains an integral number of 32-bit words. If IHL is greater than 5 (i.e., it is from 6 to 15) it means that the options field is present and must be considered. The list of options may be terminated with the option EOOL (End of Options List, 0x00); this is only necessary if the end of the options would not otherwise coincide with the end of the header. The possible options that can be put in the header are as follows:

-

Field Size (bits) Description Copied 1 Set to 1 if the options need to be copied into all fragments of a fragmented packet. Option Class 2 A general options category. 0 is for control options, and 2 is for debugging and measurement. 1 and 3 are reserved. Option Number 5 Specifies an option. Option Length 8 Indicates the size of the entire option (including this field). This field may not exist for simple options. Option Data Variable Option-specific data. This field may not exist for simple options.

- The table below shows the defined options for IPv4. The Option Type column is derived from the Copied, Option Class, and Option Number bits as defined above.[41]

-

Option Type (decimal/hexadecimal) Option Name Description 0/0x00 EOOL End of Option List 1/0x01 NOP No Operation 2/0x02 SEC Security (defunct) 7/0x07 RR Record Route 10/0x0A ZSU Experimental Measurement 11/0x0B MTUP MTU Probe 12/0x0C MTUR MTU Reply 15/0x0F ENCODE ENCODE 25/0x19 QS Quick-Start 30/0x1E EXP RFC3692-style Experiment 68/0x44 TS Time Stamp 82/0x52 TR Traceroute 94/0x5E EXP RFC3692-style Experiment 130/0x82 SEC Security (RIPSO) 131/0x83 LSR Loose Source Route 133/0x85 E-SEC Extended Security (RIPSO) 134/0x86 CIPSO Commercial IP Security Option 136/0x88 SID Stream ID 137/0x89 SSR Strict Source Route 142/0x8E VISA Experimental Access Control 144/0x90 IMITD IMI Traffic Descriptor 145/0x91 EIP Extended Internet Protocol 147/0x93 ADDEXT Address Extension 148/0x94 RTRALT Router Alert 149/0x95 SDB Selective Directed Broadcast 151/0x97 DPS Dynamic Packet State 152/0x98 UMP Upstream Multicast Packet 158/0x9E EXP RFC3692-style Experiment 205/0xCD FINN Experimental Flow Control 222/0xDE EXP RFC3692-style Experiment

Data

Edit

The packet payload is not included in the checksum. Its contents are interpreted based on the value of the Protocol header field.

List of IP protocol numbers contains a complete list of payload protocol types. Some of the common payload protocols include:

| Protocol Number | Protocol Name | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Internet Control Message Protocol | ICMP |

| 2 | Internet Group Management Protocol | IGMP |

| 6 | Transmission Control Protocol | TCP |

| 17 | User Datagram Protocol | UDP |

| 41 | IPv6 encapsulation | ENCAP |

| 89 | Open Shortest Path First | OSPF |

| 132 | Stream Control Transmission Protocol | SCTP |

Fragmentation and reassembly

Edit

The Internet Protocol enables traffic between networks. The design accommodates networks of diverse physical nature; it is independent of the underlying transmission technology used in the link layer. Networks with different hardware usually vary not only in transmission speed, but also in the maximum transmission unit (MTU). When one network wants to transmit datagrams to a network with a smaller MTU, it may fragment its datagrams. In IPv4, this function was placed at the Internet Layer and is performed in IPv4 routers limiting exposure to these issues by hosts.

In contrast, IPv6, the next generation of the Internet Protocol, does not allow routers to perform fragmentation; hosts must perform Path MTU Discovery before sending datagrams.

Fragmentation

Edit

When a router receives a packet, it examines the destination address and determines the outgoing interface to use and that interface’s MTU. If the packet size is bigger than the MTU, and the Do not Fragment (DF) bit in the packet’s header is set to 0, then the router may fragment the packet.

The router divides the packet into fragments. The maximum size of each fragment is the outgoing MTU minus the IP header size (20 bytes minimum; 60 bytes maximum). The router puts each fragment into its own packet, each fragment packet having the following changes:

- The total length field is the fragment size.

- The more fragments (MF) flag is set for all fragments except the last one, which is set to 0.

- The fragment offset field is set, based on the offset of the fragment in the original data payload. This is measured in units of 8-byte blocks.

- The header checksum field is recomputed.

For example, for an MTU of 1,500 bytes and a header size of 20 bytes, the fragment offsets would be multiples of (0, 185, 370, 555, 740, etc.).

It is possible that a packet is fragmented at one router, and that the fragments are further fragmented at another router. For example, a packet of 4,520 bytes, including a 20 bytes IP header is fragmented to two packets on a link with an MTU of 2,500 bytes:

| Fragment | Size (bytes) |

Header size (bytes) |

Data size (bytes) |

Flag More fragments |

Fragment offset (8-byte blocks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2,500 | 20 | 2,480 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 2,040 | 20 | 2,020 | 0 | 310 |

The total data size is preserved: 2,480 bytes + 2,020 bytes = 4,500 bytes. The offsets are and .

When forwarded to a link with an MTU of 1,500 bytes, each fragment is fragmented into two fragments:

| Fragment | Size (bytes) |

Header size (bytes) |

Data size (bytes) |

Flag More fragments |

Fragment offset (8-byte blocks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,500 | 20 | 1,480 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1,020 | 20 | 1,000 | 1 | 185 |

| 3 | 1,500 | 20 | 1,480 | 1 | 310 |

| 4 | 560 | 20 | 540 | 0 | 495 |

Again, the data size is preserved: 1,480 + 1,000 = 2,480, and 1,480 + 540 = 2,020.

Also in this case, the More Fragments bit remains 1 for all the fragments that came with 1 in them and for the last fragment that arrives, it works as usual, that is the MF bit is set to 0 only in the last one. And of course, the Identification field continues to have the same value in all re-fragmented fragments. This way, even if fragments are re-fragmented, the receiver knows they have initially all started from the same packet.

The last offset and last data size are used to calculate the total data size: .

Reassembly

Edit

A receiver knows that a packet is a fragment, if at least one of the following conditions is true:

- The flag more fragments is set, which is true for all fragments except the last.

- The field fragment offset is nonzero, which is true for all fragments except the first.

The receiver identifies matching fragments using the source and destination addresses, the protocol ID, and the identification field. The receiver reassembles the data from fragments with the same ID using both the fragment offset and the more fragments flag. When the receiver receives the last fragment, which has the more fragments flag set to 0, it can calculate the size of the original data payload, by multiplying the last fragment’s offset by eight and adding the last fragment’s data size. In the given example, this calculation was bytes. When the receiver has all fragments, they can be reassembled in the correct sequence according to the offsets to form the original datagram.

Assistive protocols

Edit

IP addresses are not tied in any permanent manner to networking hardware and, indeed, in modern operating systems, a network interface can have multiple IP addresses. In order to properly deliver an IP packet to the destination host on a link, hosts and routers need additional mechanisms to make an association between the hardware address[b] of network interfaces and IP addresses. The Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) performs this IP-address-to-hardware-address translation for IPv4. In addition, the reverse correlation is often necessary. For example, unless an address is preconfigured by an administrator, when an IP host is booted or connected to a network it needs to determine its IP address. Protocols for such reverse correlations include Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP), Bootstrap Protocol (BOOTP) and, infrequently, reverse ARP.

See also

Edit

- History of the Internet

- List of assigned /8 IPv4 address blocks

Notes

Edit

- ^ As an April Fools’ joke, proposed for use in RFC 3514 as the «Evil bit»

- ^ For IEEE 802 networking technologies, including Ethernet, the hardware address is a MAC address.

References

Edit

This article was adapted from the following source under a CC BY 4.0 license (2022) :

Michel Bakni; Sandra Hanbo (9 December 2022). «A Survey on Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4)» (PDF). WikiJournal of Science. doi:10.15347/WJS/2022.002. ISSN 2470-6345. OCLC 9708517136. S2CID 254665961. Wikidata Q104661268.

- ^ «BGP Analysis Reports». BGP Reports. Retrieved 2013-01-09.

- ^ «IPv6 – Google». www.google.com. Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ «IANA IPv4 Special-Purpose Address Registry». www.iana.org. Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ Cotton, Michelle; Vegoda, Leo (January 2010). «RFC 5735 — Special Use IPv4 Addresses». datatracker.ietf.org. Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ «A Brief History of IPv4». IPv4 Market Group. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- ^ «Understanding IP Addressing: Everything You Ever Wanted To Know» (PDF). 3Com. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2001.

- ^ a b c d e M. Cotton; L. Vegoda; B. Haberman (April 2013). R. Bonica (ed.). Special-Purpose IP Address Registries. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC6890. ISSN 2070-1721. BCP 153. RFC 6890. Best Common Practice. Obsoletes RFC 4773, 5156, 5735 and 5736. Updated by RFC 8190.

- ^ a b c d Y. Rekhter; B. Moskowitz; D. Karrenberg; G. J. de Groot; E. Lear (February 1996). Address Allocation for Private Internets. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC1918. BCP 5. RFC 1918. Best Common Practice. Obsoletes RFC 1627 and 1597. Updated by RFC 6761.

- ^ J. Weil; V. Kuarsingh; C. Donley; C. Liljenstolpe; M. Azinger (April 2012). IANA-Reserved IPv4 Prefix for Shared Address Space. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC6598. ISSN 2070-1721. BCP 153. RFC 6598. Best Common Practice. Updates RFC 5735.

- ^ S. Cheshire; B. Aboba; E. Guttman (May 2005). Dynamic Configuration of IPv4 Link-Local Addresses. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC3927. RFC 3927. Proposed Standard.

- ^ a b c J. Arkko; M. Cotton; L. Vegoda (January 2010). IPv4 Address Blocks Reserved for Documentation. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC5737. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 5737. Informational. Updates RFC 1166.

- ^ O. Troan (May 2015). B. Carpenter (ed.). Deprecating the Anycast Prefix for 6to4 Relay Routers. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC7526. BCP 196. RFC 7526. Best Common Practice. Obsoletes RFC 3068 and 6732.

- ^ C. Huitema (June 2001). An Anycast Prefix for 6to4 Relay Routers. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC3068. RFC 3068. Informational. Obsoleted by RFC 7526.

- ^ S. Bradner; J. McQuaid (March 1999). Benchmarking Methodology for Network Interconnect Devices. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC2544. RFC 2544. Informational. Updated by: RFC 6201 and RFC 6815.

- ^ a b M. Cotton; L. Vegoda; D. Meyer (March 2010). IANA Guidelines for IPv4 Multicast Address Assignments. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC5771. ISSN 2070-1721. BCP 51. RFC 5771. Best Common Practice. Obsoletes RFC 3138 and 3171. Updates RFC 2780.

- ^ S. Venaas; R. Parekh; G. Van de Velde; T. Chown; M. Eubanks (August 2012). Multicast Addresses for Documentation. Internet Engineering Task Force. doi:10.17487/RFC6676. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 6676. Informational.

- ^ J. Reynolds, ed. (January 2002). Assigned Numbers: RFC 1700 is Replaced by an On-line Database. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC3232. RFC 3232. Informational. Obsoletes RFC 1700.

- ^ J. Reynolds; J. Postel (October 1984). ASSIGNED NUMBERS. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC0923. RFC 923. Obsolete. Obsoleted by RFC 943. Obsoletes RFC 900.

Special Addresses: In certain contexts, it is useful to have fixed addresses with functional significance rather than as identifiers of specific hosts. When such usage is called for, the address zero is to be interpreted as meaning «this», as in «this network».

- ^ a b R. Braden, ed. (October 1989). Requirements for Internet Hosts — Communication Layers. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC1122. STD 3. RFC 1122. Internet Standard. Updated by RFC 1349, 4379, 5884, 6093, 6298, 6633, 6864, 8029 and 9293.

- ^ A. Retana; R. White; V. Fuller; D. McPherson (December 2000). Using 31-Bit Prefixes on IPv4 Point-to-Point Links. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC3021. RFC 3021. Proposed Standard.

- ^ Almquist, Philip; Kastenholz, Frank (December 1993). «Towards Requirements for IP Routers». Internet Engineering Task Force.

- ^ P. Almquist (November 1994). F. Kastenholz (ed.). Towards Requirements for IP Routers. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC1716. RFC 1716. Obsolete. Obsoleted by RFC 1812.

- ^ F. Baker, ed. (June 1995). Requirements for IP Version 4 Routers. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC1812. RFC 1812. Proposed Standard. Obsoletes RFC 1716 and 1009. Updated by RFC 2644 and 6633.

- ^ «Understanding and Configuring the ip unnumbered Command». Cisco. Retrieved 2021-11-25.

- ^ «World ‘running out of Internet addresses’«. Archived from the original on 2011-01-25. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ^ Smith, Lucie; Lipner, Ian (3 February 2011). «Free Pool of IPv4 Address Space Depleted». Number Resource Organization. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ ICANN,nanog mailing list. «Five /8s allocated to RIRs – no unallocated IPv4 unicast /8s remain».

- ^ Asia-Pacific Network Information Centre (15 April 2011). «APNIC IPv4 Address Pool Reaches Final /8». Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ S. Deering; R. Hinden (December 1998). Internet Protocol, Version 6 (IPv6) Specification. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC2460. RFC 2460. Obsolete. Obsoleted by RFC 8200. Obsoletes RFC 1883. Updated by RFC 5095, 5722, 5871, 6437, 6564, 6935, 6946, 7045 and 7112.

- ^ R. Fink; R. Hinden (March 2004). 6bone (IPv6 Testing Address Allocation) Phaseout. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC3701. RFC 3701. Informational. Obsoletes RFC 2471.

- ^ 2016 IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Innovative Business Practices for the Transformation of Societies (EmergiTech). Piscataway, NJ: University of Technology, Mauritius, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. August 2016. ISBN 9781509007066. OCLC 972636788.

- ^ Partridge, C.; Kastenholz, F. (December 1994). «6.2 IP Header Checksum». Technical Criteria for Choosing IP The Next Generation (IPng). p. 26. sec. 6.2. doi:10.17487/RFC1726. RFC 1726.

- ^ J. Postel, ed. (September 1981). INTERNET PROTOCOL — DARPA INTERNET PROGRAM PROTOCOL SPECIFICATION. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC0791. STD 5. RFC 791. IEN 128, 123, 111, 80, 54, 44, 41, 28, 26. Internet Standard. Obsoletes RFC 760. Updated by RFC 1349, 2474 and 6864.

- ^ K. Nichols; S. Blake; F. Baker; D. Black (December 1998). Definition of the Differentiated Services Field (DS Field) in the IPv4 and IPv6 Headers. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC2474. RFC 2474. Proposed Standard. Obsoletes RFC 1455 and 1349. Updated by RFC 3168, 3260 and 8436.

- ^ K. Ramakrishnan; S. Floyd; D. Black (September 2001). The Addition of Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN) to IP. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC3168. RFC 3168. Proposed Standard. Obsoletes RFC 2481. Updates RFC 2474, 2401 and 793. Updated by RFC 4301, 6040 and 8311.

- ^ Savage, Stefan (2000). «Practical network support for IP traceback». ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review. 30 (4): 295–306. doi:10.1145/347057.347560.

- ^ J. Touch (February 2013). Updated Specification of the IPv4 ID Field. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC6864. ISSN 2070-1721. RFC 6864. Proposed Standard. Updates RFC 791, 1122 and 2003.

- ^ Bhardwaj, Rashmi (2020-06-04). «Fragment Offset — IP With Ease». ipwithease.com. Retrieved 2022-11-21.

- ^ J. Postel (September 1981). ASSIGNED NUMBERS. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC0790. RFC 790. Obsolete. Obsoleted by RFC 820. Obsoletes RFC 776, 770, 762, 758, 755, 750, 739, 604, 503, 433 and 349.Obsoletes IENs: 127, 117, 93.

- ^ «Cisco unofficial FAQ». Retrieved 2012-05-10.

- ^ «Internet Protocol Version 4 (IPv4) Parameters».

External links

Edit

- Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA)

- IP, Internet Protocol Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine — IP Header Breakdown, including specific options

- IP Mobility Support for IPv4. RFC 3344.

- Official current state of IPv4/8 allocations, as maintained by IANA

Основной целью для пользователей сети интернет является передача и получение данных. При этом мало кто из рядовых посетителей веб-ресурсов задумывается, каким образом тот или иной контент достигает конечной точки именно на вашем устройстве – смартфоне, планшете или ноутбуке. Для передачи информационных данных из точки А в точку Б применяется специальный протокол сетевого взаимодействия. Наибольшее распространение получил протокол интернета версии TCP/IPv4 (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol).

Немного истории

Протоколы управления передачей информации по сетям связи разработаны учеными Винтоном Грей Серфом и Робертом Эллиотом Каном в середине семидесятых годов прошлого столетия по заказу оборонного ведомства США. В то время Пентагон всерьез рассматривал вероятность возникновения глобальной ядерной войны. Стояла задача обеспечения непрерывной передачи данных по сетям связи даже в случае выхода из строя половины оборудования, размещенного в различных точках страны. Существовавшие на тот момент способы трансляции подразумевали соединение между узлами по прямым каналам связи. В случае отказа любого из них передача данных прерывалась. Протокол IPv4 впервые использовали в 1983 году в сети передачи данных ARPANET, явившейся прототипом современного интернета.

Комьюнити теперь в Телеграм

Подпишитесь и будьте в курсе последних IT-новостей

Подписаться

Принцип работы протокола IPv4

Internet Protocol представляет собой датаграмму, содержит заголовок и полезную нагрузку. Заголовок шифрует адреса источника и назначение информационного пакета, в то время как полезная нагрузка переносит фактические данные. В отличие от сетей прямой коммутации канала, критичных к выходу из строя любого транзитного узла, передача данных с помощью интернет-протокола IPv4 осуществляется пакетным способом. При этом используются разные маршруты передачи ip-пакетов. Допустима ситуация, когда пакеты нижнего уровня достигают конечного узла раньше, чем пакеты верхнего. Некоторые из них теряются во время трансляции. В этом случае посылается повторный запрос, происходит восстановление потерянных фрагментов.

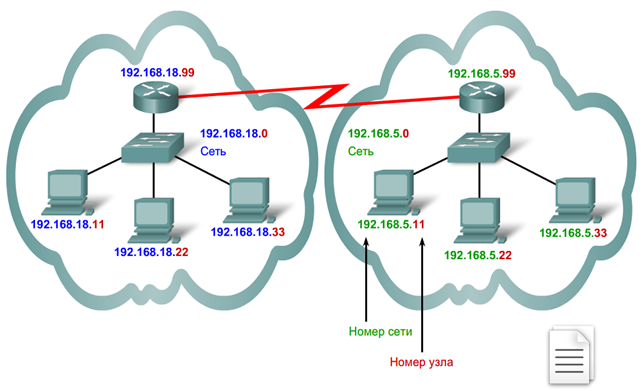

Каждый сетевой узел в модели TCP/IP имеет собственный IP-адрес. Это обеспечивает гарантированную идентификацию устройств при установке соединения и обмене данными. В то же время отличают два уровня распределения адресов по протоколу TCP/ IPv4 – публичные и частные. Первые уникальны для всех без исключения устройств, осуществляющих обмен данными в общемировой WEB-сети. Например, IP-адрес 8.8.8.8 принадлежит компании Google и является адресом публичного DNS-сервера компании. При построении локальной подсети Ethernet идентификация внутренних устройств передачи данных осуществляется путем назначения собственных ip-адресов для каждой единицы оборудования. Коммутация осуществляется через порты роутера (маршрутизатора), каждому присваивается отдельный сетевой адрес с возможным дополнительным разделением на подсети за счет использования маски IP-адреса.

Изначально адресация в IP-сетях систематизировалась по классовому принципу путем деления на большие блоки, что делало ее неудобной в использовании как конечными пользователями, так и провайдерами. Ей на смену пришла бесклассовая схема под названием Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR).

Основной атрибут протокола TCP/IPv4, его адрес, состоит из тридцати двух бит (четырех байт) и записывается четырьмя десятичными числами от 0 до 255, которые разделены точками. Есть альтернативные способы записи (двоичное, десятичное, без точки и т.д.), но они не меняют принципа работы протокола. В стандартном формате запись CIDR производится в виде IP-адреса, следующего за ним символа «/» и числа, обозначающего битовую маску подсети: 13.14.15.0/24. В данной комбинации число 24 означает количество битов в маске подсети, имеющих приоритетное значение. Полный IP-адрес состоит из 32 бит, маской являются старшие 24, соответственно, общее количество возможных адресов в сети составит 32 — 24 = 8 бит (256 IP-адресов). В этом диапазоне описываются сети, состоящие из различного количества доступных адресов путем их вариативной комбинации. Одна большая сеть может быть раздроблена на несколько более мелких подсетей нижнего уровня.

Режимы адресации протокола версии IPv4

Протокол IPv4 поддерживает три режима адресации:

- Одноадресный. При использовании данного режима данные передаются только на один сетевой узел, причем каждый из них может являться как отправителем, так и получателем. Поле адреса назначения содержит 32-битный IP-адрес устройства-получателя. Одноадресный режим используется чаще всего при обращении к интернет-протоколу.

- Широковещательный. При его использовании все устройства, подключенные к сети с множественным доступом, имеют возможность получения и обработки датаграмм, передаваемых по протоколу TCP/IPv4. Для этого поле ip-адреса назначения включает в себя специальный широковещательный код идентификации.

- Многоадресный. Согласно правилам обработки данных по протоколу IPv4, сюда входят адреса в диапазоне от 224.0.0.0 до 239.255.255.255. Режим объединяет два предыдущих, определяется наиболее значимой моделью 1110. В этом пакете адрес назначения содержит специальный код, который начинается с 224.x.x.x и может использоваться более чем одним узлом.

Для домашних сетевых устройств, будь то компьютер, смартфон или холодильник с функцией контроля через соединение Wi-Fi, назначается один общий ip-адрес. Согласно протоколу IPv4 он присваивается провайдером и закрепляется на уровне сетевого коммуникационного оборудования – роутера. Данный IP-адрес может быть статическим (неизменным) либо динамическим, меняющимся при отключении роутера от сети.

Протокол IPv4 в эталонной модели сетевого взаимодействия OSI 7

Модель OSI описывает общие принципы взаимодействия сетевых устройств по иерархическому признаку, состоящему из семи уровней: физического, канального, сетевого, транспортного, сеансового, представления, прикладного.

Как видим, протокол интернета TCP/IPv4 относится к третьему по счету уровню, сетевому. На этом уровне модели OSI происходит формирование оптимальных маршрутов и путей передачи данных между устройствами с учетом нагрузки на узлы сети. Здесь же происходит процесс трансляции – преобразования логических сетевых адресов в физические и наоборот. На программно-физическом уровне эту задачу выполняют роутеры, установленные у провайдеров и в конечной точке подключения интернета. Каждый уровень взаимодействует с верхним и нижним в обе стороны, выполняя определенную функцию обработки и передачи данных. Так третий уровень модели OSI, получив закодированную информацию от четвертого, делит ее на фрагменты, добавляя служебную информацию, и передает на второй уровень. Либо наоборот, при поступлении данных со второго сегмента на сетевом уровне происходит обработка и объединение пакетов, их передача на вышестоящий по иерархической цепочке модели OSI.

Данную модель не зря называют идеальной, так как она описывает общие принципы сетевого взаимодействия. На момент ее появления весь мир уже активно использовал стек протоколов IPv4. Причем модель TCP/IP более точно и правильно описывает существующие процессы передачи данных по сетям взаимодействия.

Любопытно. Разделением и присвоением IP-адресов занимаются четыре некоммерческих организации, разделенные по региональному принципу: RIPE NCC отвечает за Европу, ARIN действует на территории Америки, APNIC – в Азии и Тихоокеанском регионе, LACNIC – в Латинской Америке и на Карибах. Причем Россию отнесли в данной классификации к европейской RIPE. На самом деле полномочия выдачи ip-адресов делегированы локальным интернет-регистраторам (LIR), коими являются наиболее крупные провайдеры. Именно они работают с конечными пользователями в этом вопросе, в том числе финансово содержат вышестоящего регистратора за счет роялти.

Заключение

При всех своих достоинствах протокол интернета IPv4 имеет один критичный недостаток. Количество адресов, созданных с его помощью, не может превысить цифру 4 294 967 296 (минимальный адрес — 0.0.0.0, максимальный — 255.255.255.255). С учетом того, что население земного шара составляет более семи миллиардов человек, а количество всевозможных сетевых устройств растет ежедневно, предельный порог довольно близок. Согласно прогнозу RIPE NCC, в ближайшее время компаниям придется перекупать IP-адреса или ждать, когда они появятся в свободном доступе. Стоимость одного IP-адреса может составить $12-18, при этом минимальный пакет должен состоять не меньше чем из 256 адресов.

Здравствуйте, дорогие читатели! Сегодня мы коротенько рассмотрим протокол интернета версии 4. Но если быть точнее, это не совсем протокол именно интернета. По сути, это простая адресация как в локальной, так и в глобальной сети. На данный момент четвертый протокол (кратко обозначается как IPv4) чаще используется в сетях. И имеет вид:

123.34.25.57

То есть это 4 цифры, разделённые точками. Каждая цифра может иметь значение от 0 до 255. TCP IPv4 – первые три буквы расшифровываются как Transmission Control Protocol. Именно этот протокол и используется в сетях для передачи данных.

Содержание

- Глобальная и локальная сетка

- Как настроить IPv4

- На компьютере или ноутбуке

- На роутере

- Задать вопрос автору статьи

Глобальная и локальная сетка

Прежде чем приступать к настройке IPv4 нужно немного понять отличие глобальной сети и локальной. Из названия понятно, что глобальная сетка — это как раз тот самый безграничный интернет. Доступ к нему предоставляется именно провайдером, который может просто прокинуть вам в дом или квартиру сетевой провод.

И вот если вы его сразу же подключите, то в доме не будет локальной сетки, а доступ будет предоставляться напрямую. При этом на компе нужно будет вводить настройки IP адреса, макси, шлюза и DNS адресов, которые указаны в договоре. Но чаще всего IP адрес предоставляется коммутатором, стоящим на техническом этаже, и к которому вы и подключены. Тогда именно коммутатор будет предоставлять вам все настройки.

Но если интернет провод идёт именно к роутеру, то интернет в первую очередь настраивается на нём. А вот компьютер, ноутбук, телефон, планшет уже будут подключены именно к локальной сети интернет-центра. По которому и будет бегать интернет. Подключиться можно при это как по кабелю, так и беспроводным путём с помощью Wi-Fi.

И все локальные адреса начинаются с двух цифр: 192. 168. Следующая третья цифра — это подсеть. Например, если ваш роутеру имеет внутренний адрес 192.168.1.1, а на компе установить 192.168.0.1. То они будут находиться в разных подсетях и не будут видеть друг друга. А вот последняя цифра, должна быть уникальная для каждого устройства, находящиеся в одной подсети «локалки».

Как вы уже поняли, настраивается протокол в двух местах: на роутере и на компе. Разберём два варианта.

На компьютере или ноутбуке

Сначала комп или ноут надо подключить к любой сети – будь это роутер или провод от провайдера. Если подключение идёт от провайдера, то возьмите договор, который вам должны были дать при подключении.

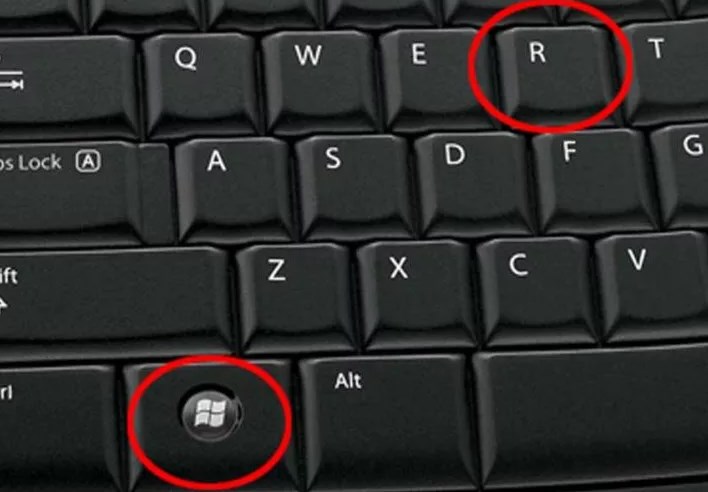

- Нажмите одновременно две клавиши: и R.

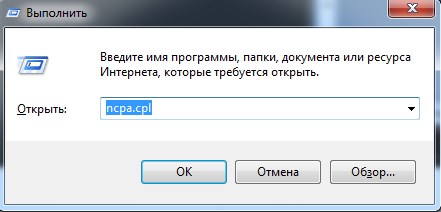

- После того как откроется окно, впишите команду «ncpa.cpl».

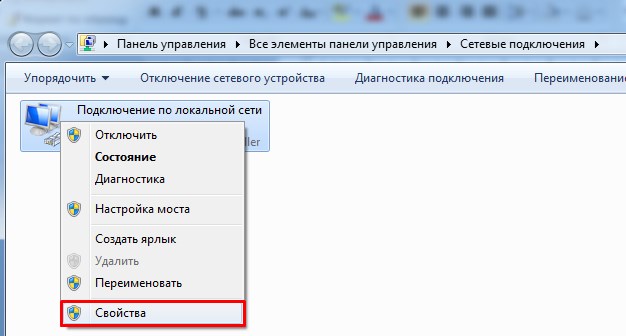

- Теперь нужно выбрать действующее подключение. Если вы подключены к роутеру по Wi-Fi – то нужно выбрать беспроводное подключение. Далее нажимаем по нему правой кнопкой и выбираем «Свойства».

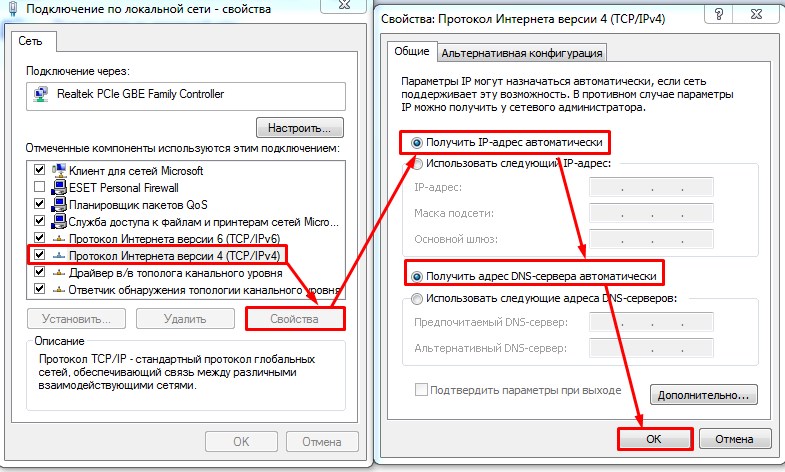

- Нажмите на наш 4 протокол и выберите «Свойства». Теперь нужно установить галочки как на картинке выше, если вы подключены к роутеру. Или если в договоре у вас идёт тип подключения как «Динамический IP» адрес. Иногда провайдеры вообще не пишут ничего по тому какое подключение они используют, тогда устанавливаем именно его.

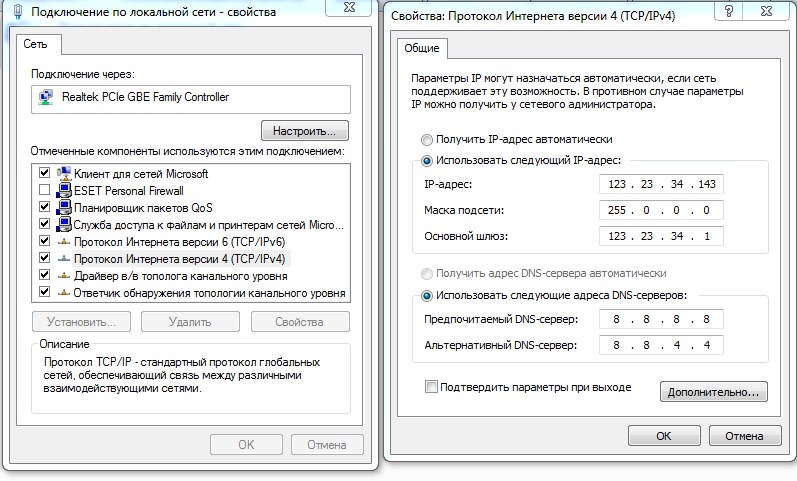

- Если у вас в бумажке указаны адреса подключения: IP, маска и DNS, то установите галочки как сверху и впишите значения с листа. Верхняя картинка представлена как пример и настройки будут у каждого – уникальные. Внимательно впишите значения из договора и нажмите «ОК».

На роутере

Нужно подключить кабель от провайдера к роутеру. Далее нужно произвести настройки интернета через Web-интерфейс. Там ничего сложного нет и все делается минут за 5-10. Принцип простой:

- Заходим в настройки.

- Настраиваем Интернет.

- Настраиваем Wi-Fi – если он нужен.

Для локальной – IP адреса для устройств настраивать не нужно, так как на всех маршрутизаторах по умолчанию стоит DHCP сервер, который и раздаёт каждому подключенному аппарату свой адрес. На нашем портале есть инструкции для всех известных интернет-центров. Просто впишите полное название модели в поисковую строку портала и прочтите инструкцию.

| Protocol stack | |

IPv4 packet |

|

| Abbreviation | IPv4 |

|---|---|

| Purpose | internetworking protocol |

| Developer(s) | DARPA |

| Introduction | 1981; 42 years ago |

| Influenced | IPv6 |

| OSI layer | Network layer |

| RFC(s) | 791 |

Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4) is the fourth version of the Internet Protocol (IP). It is one of the core protocols of standards-based internetworking methods in the Internet and other packet-switched networks. IPv4 was the first version deployed for production on SATNET in 1982 and on the ARPANET in January 1983. It is still used to route most Internet traffic today,[1] even with the ongoing deployment of Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6),[2] its successor.

IPv4 uses a 32-bit address space which provides 4,294,967,296 (232) unique addresses, but large blocks are reserved for special networking purposes.[3][4]

History[edit]

Internet Protocol version 4 is described in IETF publication RFC 791 (September 1981), replacing an earlier definition of January 1980 (RFC 760). In March 1982, the US Department of Defense decided on the Internet Protocol Suite (TCP/IP) as the standard for all military computer networking.[5]

Purpose[edit]

The Internet Protocol is the protocol that defines and enables internetworking at the internet layer of the Internet Protocol Suite. In essence it forms the Internet. It uses a logical addressing system and performs routing, which is the forwarding of packets from a source host to the next router that is one hop closer to the intended destination host on another network.

IPv4 is a connectionless protocol, and operates on a best-effort delivery model, in that it does not guarantee delivery, nor does it assure proper sequencing or avoidance of duplicate delivery. These aspects, including data integrity, are addressed by an upper layer transport protocol, such as the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP).

Addressing[edit]

For broader coverage of this topic, see IP address.

IPv4 uses 32-bit addresses which limits the address space to 4294967296 (232) addresses.

IPv4 reserves special address blocks for private networks (~18 million addresses) and multicast addresses (~270 million addresses).

Address representations[edit]

IPv4 addresses may be represented in any notation expressing a 32-bit integer value. They are most often written in dot-decimal notation, which consists of four octets of the address expressed individually in decimal numbers and separated by periods.

For example, the quad-dotted IP address 192.0.2.235 represents the 32-bit decimal number 3221226219, which in hexadecimal format is 0xC00002EB.

CIDR notation combines the address with its routing prefix in a compact format, in which the address is followed by a slash character (/) and the count of leading consecutive 1 bits in the routing prefix (subnet mask).

Other address representations were in common use when classful networking was practiced. For example, the loopback address 127.0.0.1 was commonly written as 127.1, given that it belongs to a class-A network with eight bits for the network mask and 24 bits for the host number. When fewer than four numbers were specified in the address in dotted notation, the last value was treated as an integer of as many bytes as are required to fill out the address to four octets. Thus, the address 127.65530 is equivalent to 127.0.255.250.

Allocation[edit]

In the original design of IPv4, an IP address was divided into two parts: the network identifier was the most significant octet of the address, and the host identifier was the rest of the address. The latter was also called the rest field. This structure permitted a maximum of 256 network identifiers, which was quickly found to be inadequate.

To overcome this limit, the most-significant address octet was redefined in 1981 to create network classes, in a system which later became known as classful networking. The revised system defined five classes. Classes A, B, and C had different bit lengths for network identification. The rest of the address was used as previously to identify a host within a network. Because of the different sizes of fields in different classes, each network class had a different capacity for addressing hosts. In addition to the three classes for addressing hosts, Class D was defined for multicast addressing and Class E was reserved for future applications.

Dividing existing classful networks into subnets began in 1985 with the publication of RFC 950. This division was made more flexible with the introduction of variable-length subnet masks (VLSM) in RFC 1109 in 1987. In 1993, based on this work, RFC 1517 introduced Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR),[6] which expressed the number of bits (from the most significant) as, for instance, /24, and the class-based scheme was dubbed classful, by contrast. CIDR was designed to permit repartitioning of any address space so that smaller or larger blocks of addresses could be allocated to users. The hierarchical structure created by CIDR is managed by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) and the regional Internet registries (RIRs). Each RIR maintains a publicly searchable WHOIS database that provides information about IP address assignments.

Special-use addresses[edit]

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and IANA have restricted from general use various reserved IP addresses for special purposes.[7] Notably these addresses are used for multicast traffic and to provide addressing space for unrestricted uses on private networks.

-

Special address blocks

Address block Address range Number of addresses Scope Description 0.0.0.0/8 0.0.0.0–0.255.255.255 16777216 Software Current (local, «this») network[7] 10.0.0.0/8 10.0.0.0–10.255.255.255 16777216 Private network Used for local communications within a private network.[8] 100.64.0.0/10 100.64.0.0–100.127.255.255 4194304 Private network Shared address space[9] for communications between a service provider and its subscribers when using a carrier-grade NAT. 127.0.0.0/8 127.0.0.0–127.255.255.255 16777216 Host Used for loopback addresses to the local host.[7] 169.254.0.0/16 169.254.0.0–169.254.255.255 65536 Subnet Used for link-local addresses[10] between two hosts on a single link when no IP address is otherwise specified, such as would have normally been retrieved from a DHCP server. 172.16.0.0/12 172.16.0.0–172.31.255.255 1048576 Private network Used for local communications within a private network.[8] 192.0.0.0/24 192.0.0.0–192.0.0.255 256 Private network IETF Protocol Assignments, DS-Lite (/29).[7] 192.0.2.0/24 192.0.2.0–192.0.2.255 256 Documentation Assigned as TEST-NET-1, documentation and examples.[11] 192.88.99.0/24 192.88.99.0–192.88.99.255 256 Internet Reserved.[12] Formerly used for IPv6 to IPv4 relay[13] (included IPv6 address block 2002::/16). 192.168.0.0/16 192.168.0.0–192.168.255.255 65536 Private network Used for local communications within a private network.[8] 198.18.0.0/15 198.18.0.0–198.19.255.255 131072 Private network Used for benchmark testing of inter-network communications between two separate subnets.[14] 198.51.100.0/24 198.51.100.0–198.51.100.255 256 Documentation Assigned as TEST-NET-2, documentation and examples.[11] 203.0.113.0/24 203.0.113.0–203.0.113.255 256 Documentation Assigned as TEST-NET-3, documentation and examples.[11] 224.0.0.0/4 224.0.0.0–239.255.255.255 268435456 Internet In use for IP multicast.[15] (Former Class D network.) 233.252.0.0/24 233.252.0.0-233.252.0.255 256 Documentation Assigned as MCAST-TEST-NET, documentation and examples.[15][16] 240.0.0.0/4 240.0.0.0–255.255.255.254 268435455 Internet Reserved for future use.[17] (Former Class E network.) 255.255.255.255/32 255.255.255.255 1 Subnet Reserved for the «limited broadcast» destination address.[7]

Private networks[edit]

Of the approximately four billion addresses defined in IPv4, about 18 million addresses in three ranges are reserved for use in private networks. Packets addresses in these ranges are not routable in the public Internet; they are ignored by all public routers. Therefore, private hosts cannot directly communicate with public networks, but require network address translation at a routing gateway for this purpose.

-

Reserved private IPv4 network ranges[8]

Name CIDR block Address range Number of addresses Classful description 24-bit block 10.0.0.0/8 10.0.0.0 – 10.255.255.255 16777216 Single Class A. 20-bit block 172.16.0.0/12 172.16.0.0 – 172.31.255.255 1048576 Contiguous range of 16 Class B blocks. 16-bit block 192.168.0.0/16 192.168.0.0 – 192.168.255.255 65536 Contiguous range of 256 Class C blocks.

Since two private networks, e.g., two branch offices, cannot directly interoperate via the public Internet, the two networks must be bridged across the Internet via a virtual private network (VPN) or an IP tunnel, which encapsulates packets, including their headers containing the private addresses, in a protocol layer during transmission across the public network. Additionally, encapsulated packets may be encrypted for transmission across public networks to secure the data.

Link-local addressing[edit]

RFC 3927 defines the special address block 169.254.0.0/16 for link-local addressing. These addresses are only valid on the link (such as a local network segment or point-to-point connection) directly connected to a host that uses them. These addresses are not routable. Like private addresses, these addresses cannot be the source or destination of packets traversing the internet. These addresses are primarily used for address autoconfiguration (Zeroconf) when a host cannot obtain an IP address from a DHCP server or other internal configuration methods.

When the address block was reserved, no standards existed for address autoconfiguration. Microsoft created an implementation called Automatic Private IP Addressing (APIPA), which was deployed on millions of machines and became a de facto standard. Many years later, in May 2005, the IETF defined a formal standard in RFC 3927, entitled Dynamic Configuration of IPv4 Link-Local Addresses.

Loopback[edit]

The class A network 127.0.0.0 (classless network 127.0.0.0/8) is reserved for loopback. IP packets whose source addresses belong to this network should never appear outside a host. Packets received on a non-loopback interface with a loopback source or destination address must be dropped.

First and last subnet addresses[edit]

The first address in a subnet is used to identify the subnet itself. In this address all host bits are 0. To avoid ambiguity in representation, this address is reserved.[18] The last address has all host bits set to 1. It is used as a local broadcast address for sending messages to all devices on the subnet simultaneously. For networks of size /24 or larger, the broadcast address always ends in 255.

For example, in the subnet 192.168.5.0/24 (subnet mask 255.255.255.0) the identifier 192.168.5.0 is used to refer to the entire subnet. The broadcast address of the network is 192.168.5.255.

| Type | Binary form | Dot-decimal notation |

|---|---|---|

| Network space | 11000000.10101000.00000101.00000000

|

192.168.5.0 |

| Broadcast address | 11000000.10101000.00000101.11111111

|

192.168.5.255 |

| In red, is shown the host part of the IP address; the other part is the network prefix. The host gets inverted (logical NOT), but the network prefix remains intact. |

However, this does not mean that every address ending in 0 or 255 cannot be used as a host address. For example, in the /16 subnet 192.168.0.0/255.255.0.0, which is equivalent to the address range 192.168.0.0–192.168.255.255, the broadcast address is 192.168.255.255. One can use the following addresses for hosts, even though they end with 255: 192.168.1.255, 192.168.2.255, etc. Also, 192.168.0.0 is the network identifier and must not be assigned to an interface.[19]: 31 The addresses 192.168.1.0, 192.168.2.0, etc., may be assigned, despite ending with 0.

In the past, conflict between network addresses and broadcast addresses arose because some software used non-standard broadcast addresses with zeros instead of ones.[19]: 66

In networks smaller than /24, broadcast addresses do not necessarily end with 255. For example, a CIDR subnet 203.0.113.16/28 has the broadcast address 203.0.113.31.

| Type | Binary form | Dot-decimal notation |

|---|---|---|

| Network space | 11001011.00000000.01110001.00010000

|

203.0.113.16 |

| Broadcast address | 11001011.00000000.01110001.00011111

|

203.0.113.31 |

| In red, is shown the host part of the IP address; the other part is the network prefix. The host gets inverted (logical NOT), but the network prefix remains intact. |

As a special case, a /31 network has capacity for just two hosts. These networks are typically used for point-to-point connections. There is no network identifier or broadcast address for these networks.[20]

Address resolution[edit]

Hosts on the Internet are usually known by names, e.g., www.example.com, not primarily by their IP address, which is used for routing and network interface identification. The use of domain names requires translating, called resolving, them to addresses and vice versa. This is analogous to looking up a phone number in a phone book using the recipient’s name.

The translation between addresses and domain names is performed by the Domain Name System (DNS), a hierarchical, distributed naming system that allows for the subdelegation of namespaces to other DNS servers.

Unnumbered interface[edit]

A unnumbered point-to-point (PtP) link, also called a transit link, is a link that doesn’t have an IP network or subnet number associated with it, but still has an IP address. First introduced in 1993,[21][22][23][24] Phil Karn from Qualcomm is credited as the original designer.

The purpose of a transit link is to route datagrams. They are used to free IP addresses from a scarce IP address space or to reduce the management of assigning IP and configuration of interfaces. Previously, every link needed to dedicate a /31 or /30 subnet using 2 or 4 IP addresses per point-to-point link. When a link is unnumbered, a router-id is used, a single IP address borrowed from a defined (normally a loopback) interface. The same router-id can be used on multiple interfaces.

One of the disadvantages of unnumbered interfaces is that it is harder to do remote testing and management.

Address space exhaustion[edit]

In the 1980s, it became apparent that the pool of available IPv4 addresses was depleting at a rate that was not initially anticipated in the original design of the network.[25] The main market forces that accelerated address depletion included the rapidly growing number of Internet users, who increasingly used mobile computing devices, such as laptop computers, personal digital assistants (PDAs), and smart phones with IP data services. In addition, high-speed Internet access was based on always-on devices. The threat of exhaustion motivated the introduction of a number of remedial technologies, such as:

- Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR), for smaller ISP allocations

- Unnumbered interface, removed the need on transit links.

- network address translation (NAT), removed the need for end-to-end principle.

By the mid-1990s, NAT was used pervasively in network access provider systems, along with strict usage-based allocation policies at the regional and local Internet registries.

The primary address pool of the Internet, maintained by IANA, was exhausted on 3 February 2011, when the last five blocks were allocated to the five RIRs.[26][27] APNIC was the first RIR to exhaust its regional pool on 15 April 2011, except for a small amount of address space reserved for the transition technologies to IPv6, which is to be allocated under a restricted policy.[28]

The long-term solution to address exhaustion was the 1998 specification of a new version of the Internet Protocol, IPv6.[29] It provides a vastly increased address space, but also allows improved route aggregation across the Internet, and offers large subnetwork allocations of a minimum of 264 host addresses to end users. However, IPv4 is not directly interoperable with IPv6, so that IPv4-only hosts cannot directly communicate with IPv6-only hosts. With the phase-out of the 6bone experimental network starting in 2004, permanent formal deployment of IPv6 commenced in 2006.[30] Completion of IPv6 deployment is expected to take considerable time,[31] so that intermediate transition technologies are necessary to permit hosts to participate in the Internet using both versions of the protocol.

Packet structure[edit]

An IP packet consists of a header section and a data section. An IP packet has no data checksum or any other footer after the data section.

Typically the link layer encapsulates IP packets in frames with a CRC footer that detects most errors, many transport-layer protocols carried by IP also have their own error checking.[32]

[edit]

The IPv4 packet header consists of 14 fields, of which 13 are required. The 14th field is optional and aptly named: options. The fields in the header are packed with the most significant byte first (network byte order), and for the diagram and discussion, the most significant bits are considered to come first (MSB 0 bit numbering). The most significant bit is numbered 0, so the version field is actually found in the four most significant bits of the first byte, for example.

| Offsets | Octet | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octet | Bit | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

| 0 | 0 | Version | IHL | DSCP | ECN | Total Length | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 32 | Identification | Flags | Fragment Offset | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | 64 | Time To Live | Protocol | Header Checksum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 96 | Source IP Address | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | 128 | Destination IP Address | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 160 | Options (if IHL > 5) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 56 | 448 |

- Version

- The first header field in an IP packet is the four-bit version field. For IPv4, this is always equal to 4.

- Internet Header Length (IHL)

- The IPv4 header is variable in size due to the optional 14th field (options). The IHL field contains the size of the IPv4 header; it has 4 bits that specify the number of 32-bit words in the header. The minimum value for this field is 5,[33] which indicates a length of 5 × 32 bits = 160 bits = 20 bytes. As a 4-bit field, the maximum value is 15; this means that the maximum size of the IPv4 header is 15 × 32 bits = 480 bits = 60 bytes.

- Differentiated Services Code Point (DSCP)

- Originally defined as the type of service (ToS), this field specifies differentiated services (DiffServ).[34] Real-time data streaming makes use of the DSCP field. An example is Voice over IP (VoIP), which is used for interactive voice services.

- Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN)

- This field allows end-to-end notification of network congestion without dropping packets.[35] ECN is an optional feature available when both endpoints support it and effective when also supported by the underlying network.

- Total Length

- This 16-bit field defines the entire packet size in bytes, including header and data. The minimum size is 20 bytes (header without data) and the maximum is 65,535 bytes. All hosts are required to be able to reassemble datagrams of size up to 576 bytes, but most modern hosts handle much larger packets. Links may impose further restrictions on the packet size, in which case datagrams must be fragmented. Fragmentation in IPv4 is performed in either the sending host or in routers. Reassembly is performed at the receiving host.

- Identification

- This field is an identification field and is primarily used for uniquely identifying the group of fragments of a single IP datagram. Some experimental work has suggested using the ID field for other purposes, such as for adding packet-tracing information to help trace datagrams with spoofed source addresses,[36] but any such use is now prohibited.[37]

- Flags

- A three-bit field follows and is used to control or identify fragments. They are (in order, from most significant to least significant):

- bit 0: Reserved; must be zero.[a]

- bit 1: Don’t Fragment (DF)

- bit 2: More Fragments (MF)

- If the DF flag is set, and fragmentation is required to route the packet, then the packet is dropped. This can be used when sending packets to a host that does not have resources to perform reassembly of fragments. It can also be used for path MTU discovery, either automatically by the host IP software, or manually using diagnostic tools such as ping or traceroute.

- For unfragmented packets, the MF flag is cleared. For fragmented packets, all fragments except the last have the MF flag set. The last fragment has a non-zero Fragment Offset field, differentiating it from an unfragmented packet.

- Fragment offset

- This field specifies the offset of a particular fragment relative to the beginning of the original unfragmented IP datagram. The fragmentation offset value for the first fragment is always 0. The field is 13 bits wide, so that the offset can be from 0 to 8191 (from (20 – 1) to (213 – 1)). Fragments are specified in units of 8 bytes, which is why fragment length must be a multiple of 8.[38] Therefore, the 13-bit field allows a maximum offset of (213 – 1) × 8 = 65,528 bytes, with the header length included (65,528 + 20 = 65,548 bytes), supporting fragmentation of packets exceeding the maximum IP length of 65,535 bytes.

- Time to live (TTL)

- An eight-bit time to live field limits a datagram’s lifetime to prevent network failure in the event of a routing loop. It is specified in seconds, but time intervals less than 1 second are rounded up to 1. In practice, the field is used as a hop count—when the datagram arrives at a router, the router decrements the TTL field by one. When the TTL field hits zero, the router discards the packet and typically sends an ICMP time exceeded message to the sender.

- The program traceroute sends messages with adjusted TTL values and uses these ICMP time exceeded messages to identify the routers traversed by packets from the source to the destination.

- Protocol

- This field defines the protocol used in the data portion of the IP datagram. IANA maintains a list of IP protocol numbers.[39]

- Header checksum

- The 16-bit IPv4 header checksum field is used for error-checking of the header. When a packet arrives at a router, the router calculates the checksum of the header and compares it to the checksum field. If the values do not match, the router discards the packet. Errors in the data field must be handled by the encapsulated protocol. Both UDP and TCP have separate checksums that apply to their data.

- When a packet arrives at a router, the router decreases the TTL field in the header. Consequently, the router must calculate a new header checksum.

- The checksum field is the 16 bit one’s complement of the one’s complement sum of all 16 bit words in the header. For purposes of computing the checksum, the value of the checksum field is zero.

- Source address

- This 32-bit field is the IPv4 address of the sender of the packet. It may be changed in transit by network address translation (NAT).

- Destination address

- This 32-bit field is the IPv4 address of the receiver of the packet. It may be affected by NAT.

- Options