Install git for Windows¶

-

Get a copy of the msysgit

.exeinstaller -

Double click to install git on your machine

-

Accept all the defaults

A pretend project¶

For simplicity, let us make a folder for our project in the c:\ drive.

-

Right click on the

C:\drive in Windows Explorer, select “New folder”,

namemy_idea -

Right click in

my_idea, folder, select New file, of type “Text document”.

Name itgood_idea.txt. -

Open

good_idea.txtand add some text like “This is my good idea”, and

save.

Putting the project into version control¶

Now we have a very small project, just a folder with a single file in it. We’ll

now put this folder into version control.

Initializing the repository¶

-

Right click in the

my_ideafolder, choose “Git Init Here” to initialize

the git database: -

You may notice that there is now a hidden folder called

.gitin themy_ideafolder.If you can’t see this hidden folder, you may need to change the folder viewing

options. From Windows XP explorer this is the “Tools” menu, then “Options”.

You should enable viewing hidden folders in the “View” tab:

Adding stuff to the repository¶

Now we have a git database in our folder, we need to add our file.

-

Right click in the

my_ideaagain, choose “Git Commit Tool” -

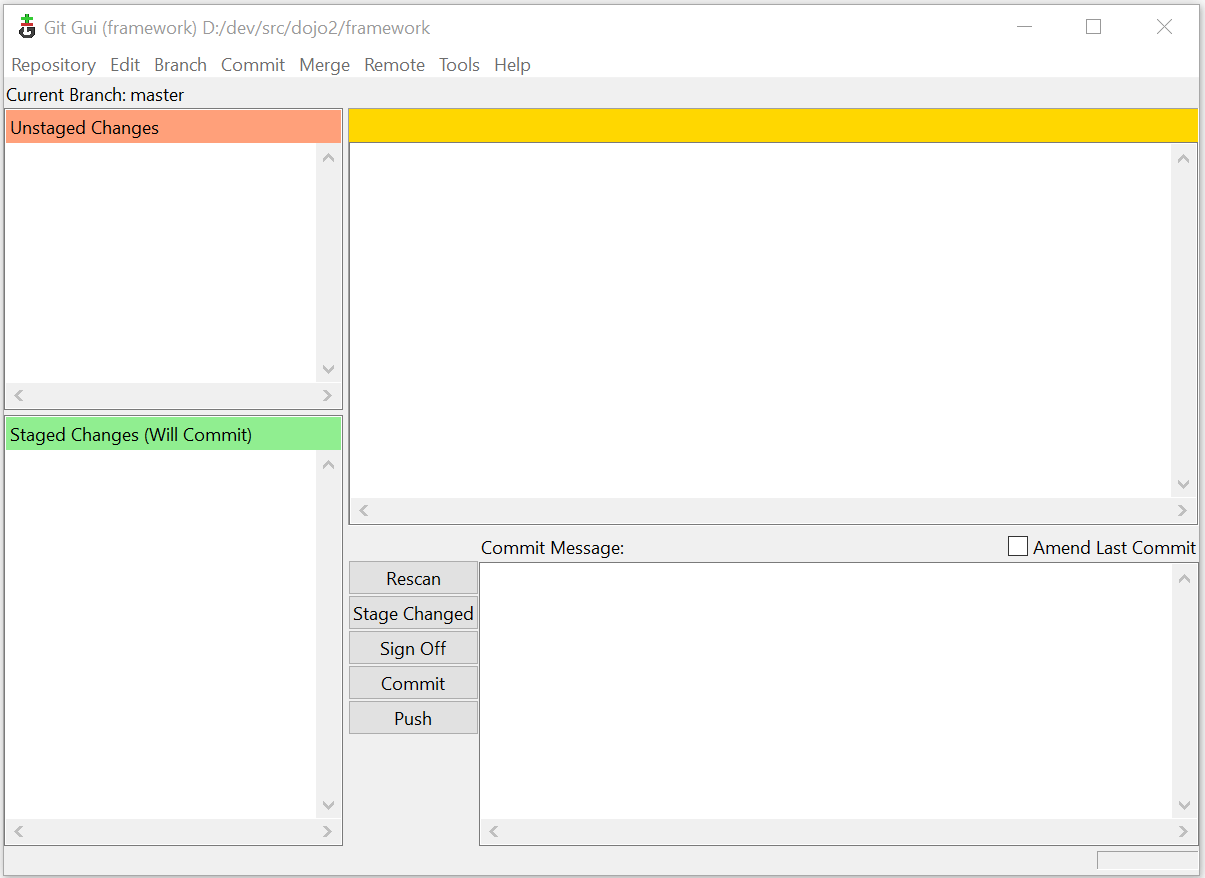

You will get a dialog like this:

Notice that our file is at the top left, and is “Unstaged”. That means that,

at the moment, it is not going to be part of any “Commit” we do. A commit is

where we record changes into the database. We do want to record our file, so -

Either click on the little icon to the left of the

good_idea.txtfilename

in the dialog, or go to the “Commit” menu, “Stage to commit” option. Notice

thegood_idea.txtfile then goes to the “Staged changes (Will Commit)”

section of the dialog. -

Add a message in the lower right box, like

The first signs of my idea. The

commit message is a reminder what set of changes the commit has. It’s very

useful to put meaningful messages here for quick reminders of what you

intended with the changes. Now click “Commit”. Congratulations!

Speak with your own voice¶

Each commit has someone who wrote the contents of the commit — the “author”. So

you can get all the blame, and all the credit, you can identify yourself to git.

That way git can see who’s doing the work (or doing the damage).

-

Right click in “my idea”, choose “Git Gui”.

-

Click on the “Repository” menu and select “Visualize master’s history”:

-

Notice that you are ‘Author: unknown’:

-

Close the history window, right click and open ‘Git Gui’ again

-

Go to menu Edit — Options. Set your username and and email address in the Right hand panel (global options).

Save. Close.

-

Let’s show ourselves that I have become myself. Make a new file

another_idea.txt. Start “Git Commit Tool” with a right click, stage the

file by clicking on the icon next to the filename, add a message and the click

commit. -

Open Git history from the Git Gui, choose the “Repository” menu, “Visualize master’s history”.

Notice that you have two commits now, and the second one has your name on it.

Making a backup¶

Now you have your changes backed up into your repository, but you will probably

want to back up the repository somewhere.

Let’s pretend to back the repository up to a shared drive (but in fact we’ll

back up to the C:\ drive).

-

Right click in the

my_ideafolder, chose “Git Gui” -

Choose menu “Remote”, “Add”:

-

Give a name for your backup (no spaces) and a path to write the backup to.

I like to add.gitto the folder name for the backup, because this will be

a backup with only the repository (the.gitsubfolder, but not the

.txtfiles): -

Select “Initialize repository and push”, then click “Add”.

-

If you get “Success” then your files have been backed up to this other folder.

Working from another machine¶

Now you can work from any computer and send changes back to the backup copy.

We can pretend to do this by making a new copy as if it was on (say) your

laptop. But in fact we’ll create the folder in the C:\ drive again.

-

Right click on the

C:\drive, choose ‘Git Gui’: -

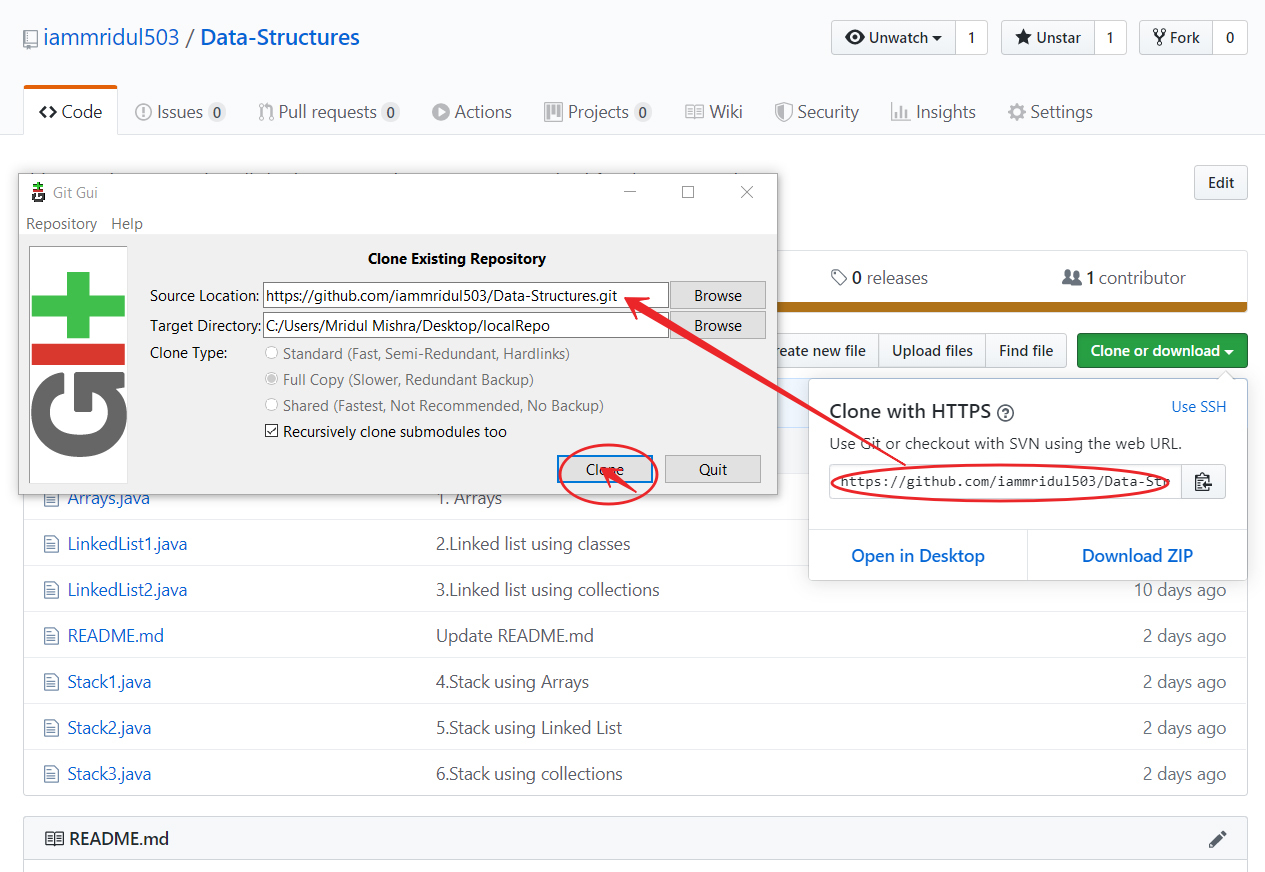

Select “Clone existing repository”. For the ‘Source location’, browse to the

backup that you just made. TypeC:\laptop_workingfor the target directory. Choose

“full copy” from the options (for safety). Click on “Clone”. -

You now have a

c:\laptop_workingfolder that is a clone of the “my_backup”

repository, and that also has the same data as thec:\my_ideafolder. -

Let’s make some changes on the laptop. Go to the

c:\laptop_working

folder. Make a new fileidea_on_laptop.txtand type some text in it.

Save. -

Right click, “Git Commit Tool”, stage the

idea_on_laptop.txtfile, add a

commit message and click “Commit”.Now you have this contents in your

laptop_workingfolder.

You put the changes back into the backup by doing a “Push”

-

Right click in

laptop_working. “Git Gui”, “Remote” menu, “Push …”On the next dialog, click “Push”.

The changes go back to the

my_backup.gitrepository.

Getting changes from a common backup¶

Let’s pretend that we’ve gone back to our original computer and we want the

changes that we pushed from the laptop.

-

Go back to the

my_ideafolder. Notice you don’t have the

idea_on_laptopfile yet. -

Right click, “Git Gui”, “Remote” menu, “Fetch from” from the

my_backup

remote.Now you have the changes in the repository (the

.gitsubdirectory)

— but not in the working tree. Specifically, we don’t have the

idea_on_laptop.txtfile in the folder yet:To get the file, we need to do a merge. This brings the changes from the

repository into the working tree. Open the “Git Gui” if it is not open.

Choose the “Merge” menu, “Local Merge” option.In the dialog, accept the

defaults and click “Merge”:Now you have your file — and you are synchronized with the laptop.

Review¶

-

Code states stored so you can

-

See what you’ve done

-

Go back to an earlier state if you make a mistake

-

Send files to and from different computers

-

-

If you are working with someone else they can add their changes

-

You can see what they did, they can see what you did

-

It’s easy to undo if one of you makes a mistake

-

This system is powerful, very useful and sometimes confusing. Consult an

expert if you get confused. It is fairly difficult to lose data if you ask an

expert after you have made a mistake or got confused.

Git has its native environment within the terminal. All the new features are updated first at the command line, and only there is the full power of Git. But plain text isn’t the simplest choice for all tasks; sometimes some users are much more comfortable with a point-and-click interface, a visual representation is what they need.

Note: There’s nothing these graphical clients can do that the command-line client can’t; the command-line is still where you’ll have the most power and control when working with your repositories.

Working with GUI

Git GUI is Tcl/Tk based graphical user interface to Git. It focuses on allowing users to make changes to their repository by making new commits, amending existing ones, creating branches, performing local merges, and fetching/pushing to remote repositories.

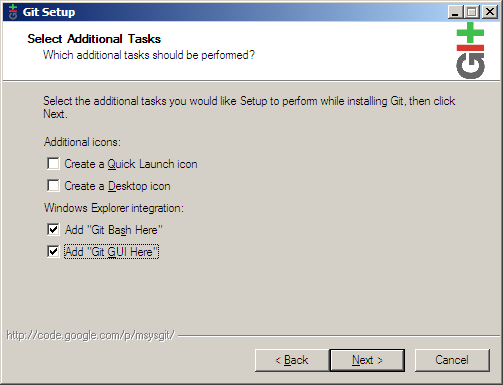

The first thing we need to do is install Git on Windows; you can do so with the following steps:

Step 1: Download and install the latest version of Git for Windows.

Step 2: Use the default options for each step in the installation.

Step 3: Remove Git Bash Desktop Icon.

Step 4: Go to Start > All Programs > Git > Git GUI and make a Desktop Shortcut.

Getting started with Git GUI

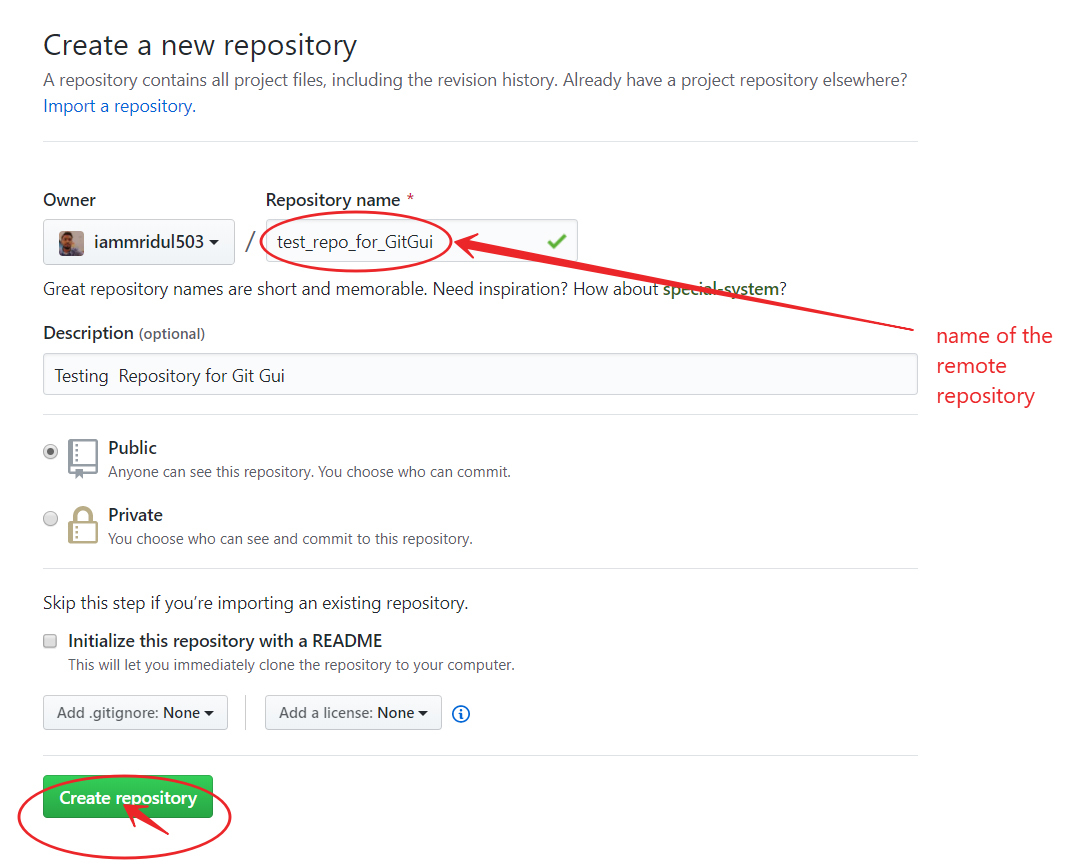

Step 1: Create Remote Repository

Now, we need a Git repository, and we’ll create a new remote repository on Github.

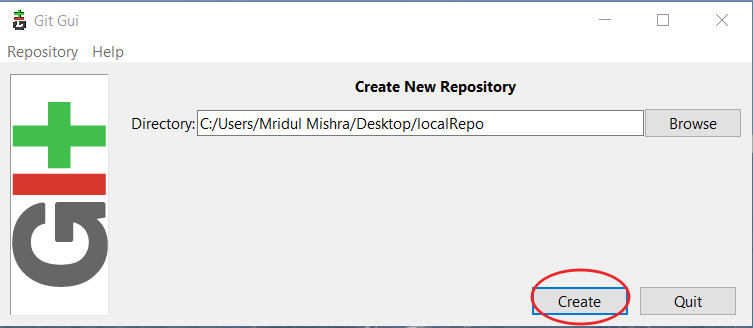

Step 2: Create a Local Repository

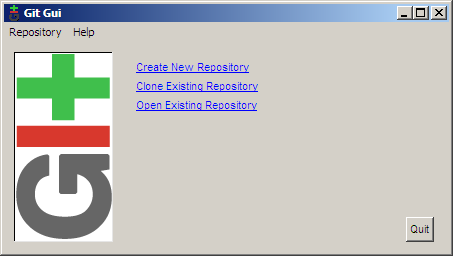

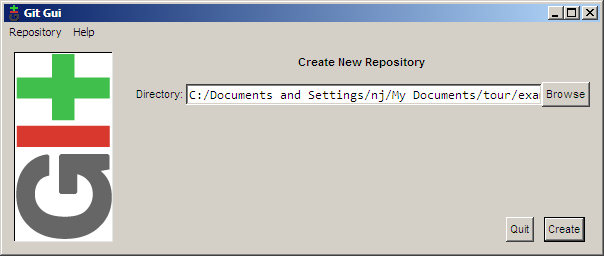

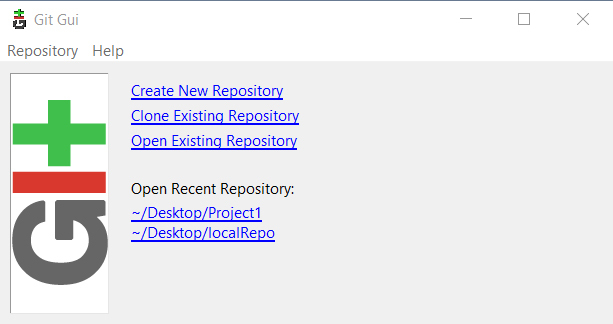

For creating a local repository: in our Git GUI, click on “Create New Repository”.

Select the location you wish to store your repository in. It is important to note that the selected repository location

MUST NOT exist.

In order for this new repository to be initialized, you must first create a file, any file, in your local repo.Then, you must Commit and Push to the remote Git repository location.

Step 3: Clone a Remote Repository to a Local Repository

In order to clone a repository, click on the “Clone Existing Repository” link in the Git GUI window. An existing repository is one that is already initialized and/or has commits pushed to it.

Note: In the Source Location field, fill in the Git remote repository location. The target directory works as same in the case of creating a local repository. Git will attempt to create it, and it will fail if it already exists.

Working with the GUI Client

The Git GUI makes it easier to perform Git-related tasks, such as staging changes, commits, and pushes.

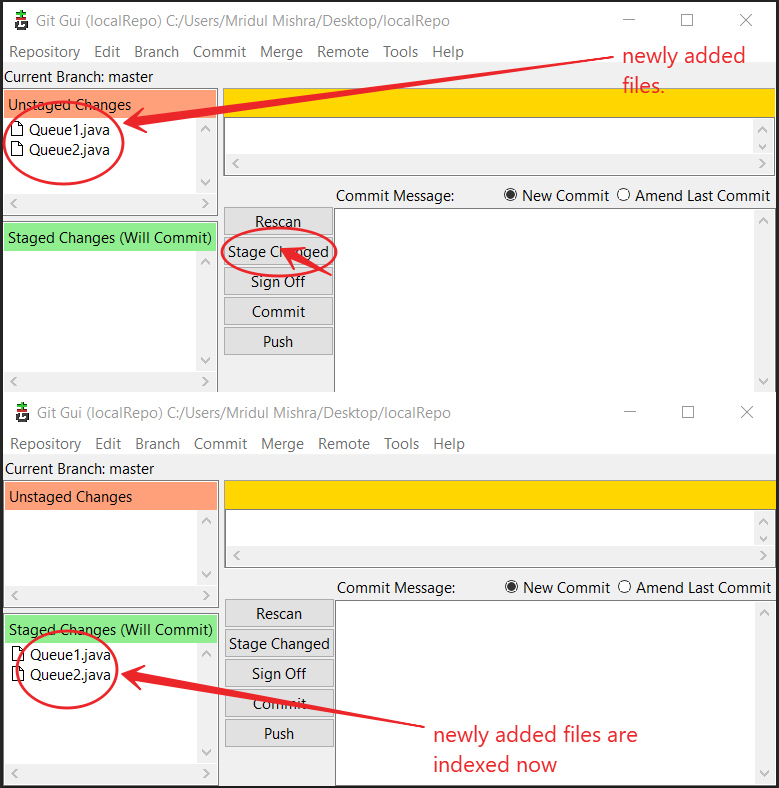

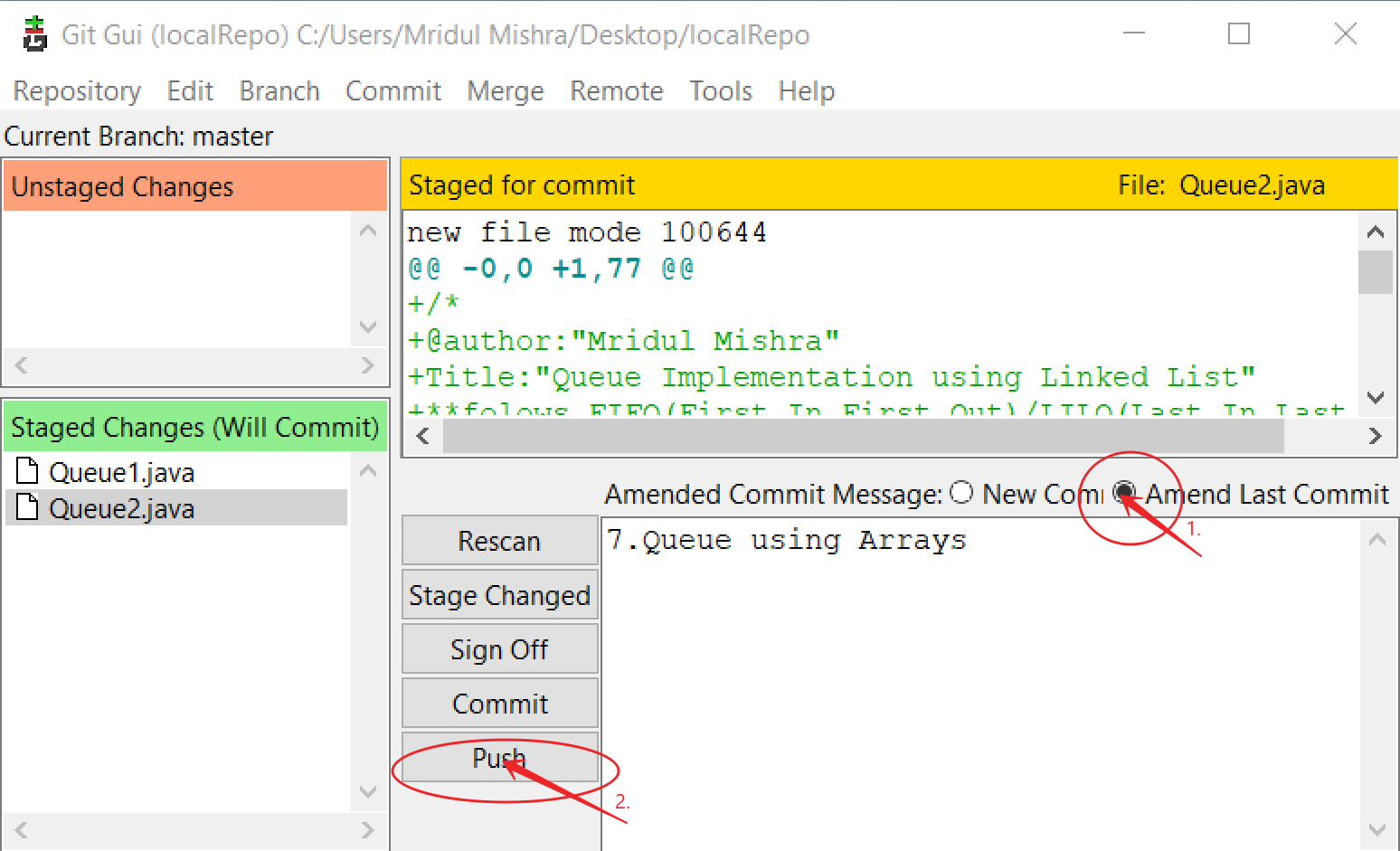

Staged Changes

When we move files to a Git directory, you will see all the files in the “Unstaged Changes” window. This basically means that new files have been added, removed, updated, etc. When we click the “Stage Changed” button, it will attempt to add all the new files to the Git index.

Git Equivalent Command: git add file_name git status

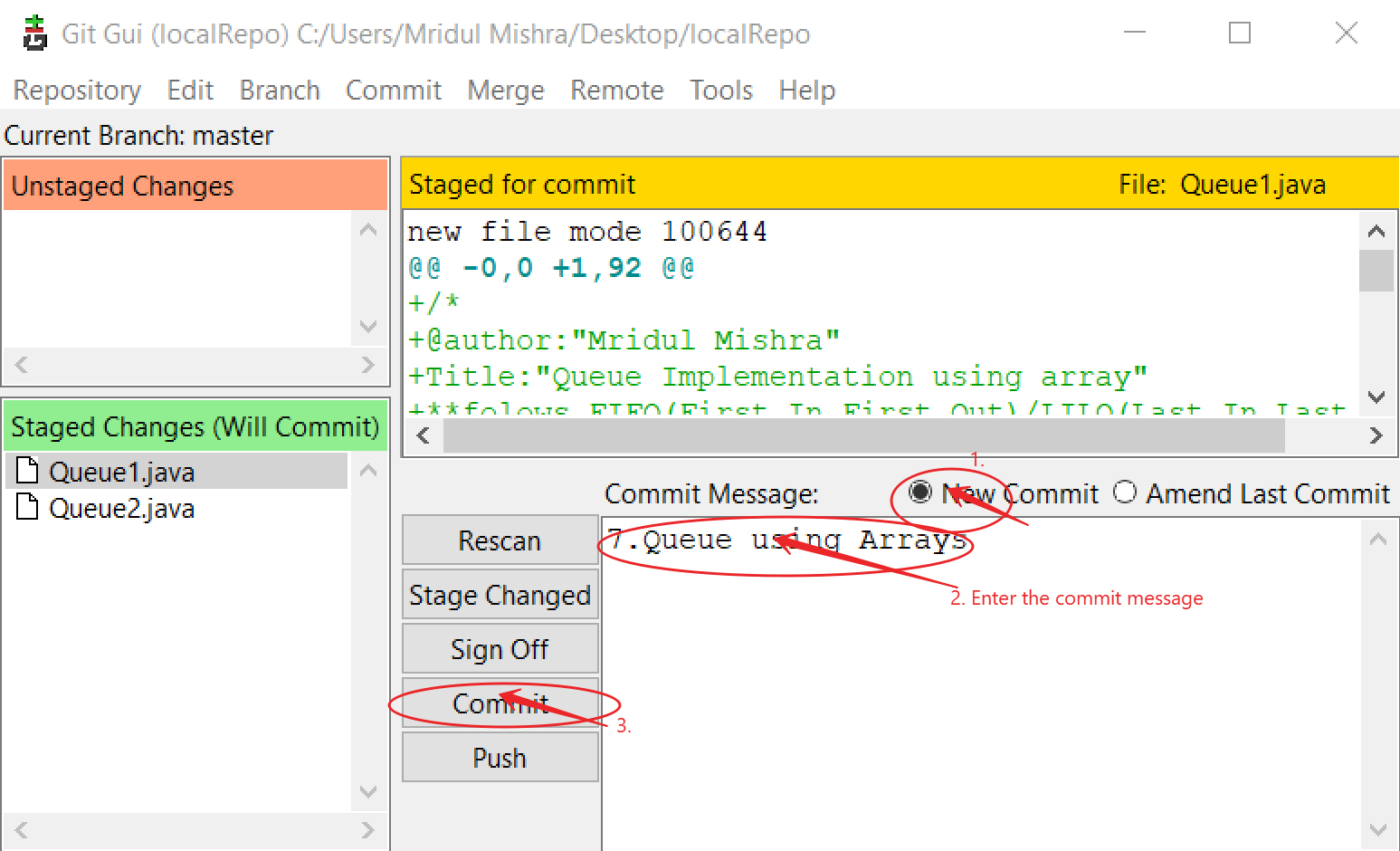

Commits

After we’ve staged your changes, we need to commit them to your local repository. Type a Commit Message that makes sense to the changes that were made. When we are done, press the Commit button.

Git Equivalent Command: git commit -m "message"

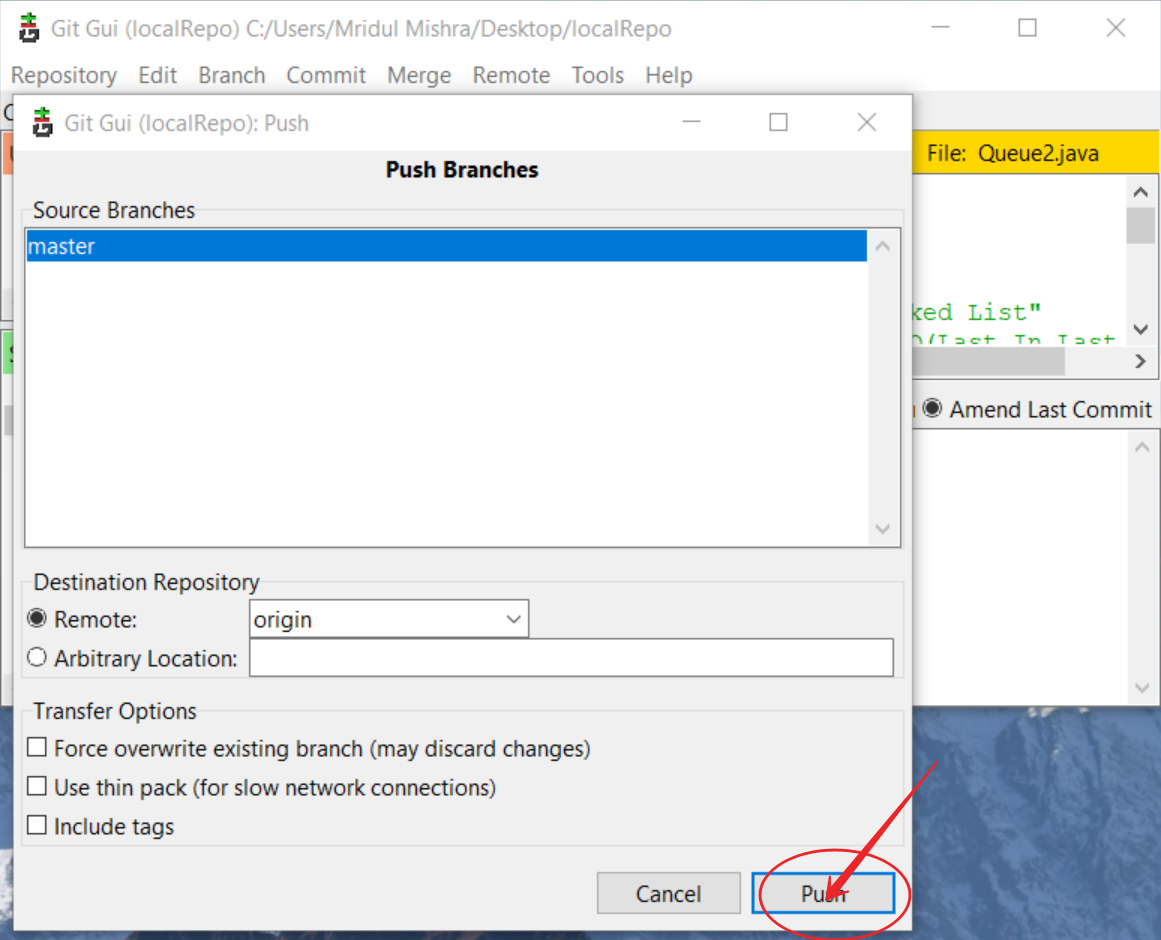

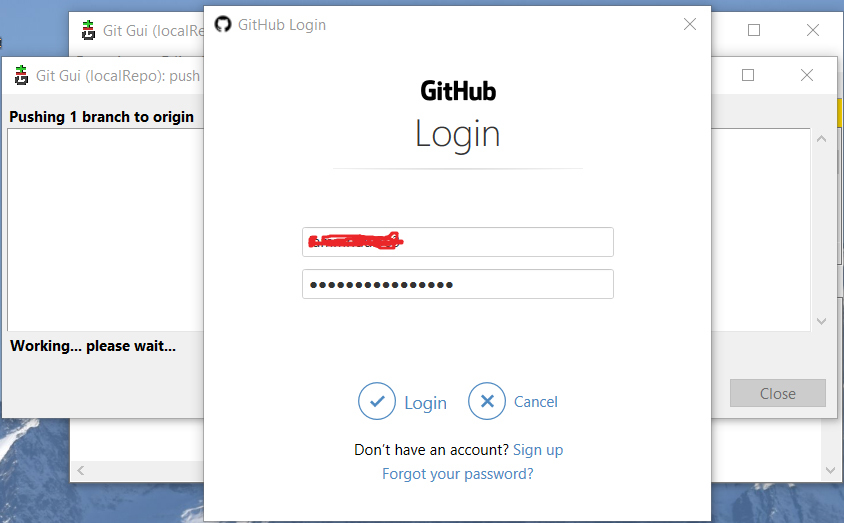

Pushing

After we have committed all the codes in the local repository, we need to push these changes to our remote repository on GitHub. Without pushing the changes, others would not be able to access the code.

Before we can proceed to push, we need set up a location to push to. Most folks refer to this location as “origin”. In Git, “origin” is a shorthand name for the remote repository that a project was originally cloned from. More precisely, it is used instead of that original repository’s URL – and thereby makes referencing much easier.

Git Equivalent Command: git push -u origin master

This way GUI makes it a lot easier to work with GIT for the users that do not prefer the command line.

Last Updated :

21 Apr, 2020

Like Article

Save Article

Getting started with Git can be a daunting task, especially if you are not at home in the command line. Fortunately, Git is a mature and widely used tool so there is a lot of reference and “How do I…?” material available. One aspect less commonly covered is using Git with some of the numerous Git GUIs available. This article will get you up and running with a basic understanding of Git concepts and how to manage your Git workflow with Git Gui, TortoiseGit, and Visual Studio Code.

Why use a GUI?

Git is a powerful, robust tool that runs on the command line by default. Using a GUI offers a more discoverable interface and some people prefer the aesthetics of GUIs over the CLI. For developers focused on writing code and using Git to collaborate with their team or contribute to OSS projects a GUI can be a pleasant tool that will comfortably handle the necessary tasks. Once you learn Git concepts you don’t necessarily need to memorize the specific steps to accomplish tasks – GUIs make it easier to discover (or rediscover!) how to accomplish a task when you know what your task is.

Git concepts

If you aren’t already familiar with software version control this short article is a good introduction.

The Git commit tree

Git stores changes in a series of commits. Every commit is identified by a unique hash. One thing that can be confusing to newcomers is that the arrows in Git tree diagrams point backwards. While the chronological flow for commits A then B then C looks like:

A → B → C

The commits are stored with parent references, not child references. A has no knowledge of B or C; B records that A is its parent and C records that B is its parent. This gives us a commit tree like:

A ← B ← C

File concepts in Git

- Working Tree: all of the files in the file system in your project folder. Git may ignore some files depending on the configuration in the .gitignore file.

- Staging Area: the “commit” command only commits files that have been added to staging. File diffs can be viewed between working tree content and staged content.

- Repository: the Git repository contains all commits and other Git data.

You add files to the working tree simply by adding them to your file system. Git’s “add” command, or Git Gui’s “Stage to Commit” action adds changes to the staging area. Git’s “commit” command adds changes to the repository.

Getting started

The first step is to create a Git repository. We’ll start with TortoiseGit for this task since its context menu is integrated into Windows Explorer.

Tip: The Tortoise VCS clients have quite a lineage going back to TortoiseSVN and even TortoiseCVS. If you have used those you’ll be right at home with TortoiseGit.

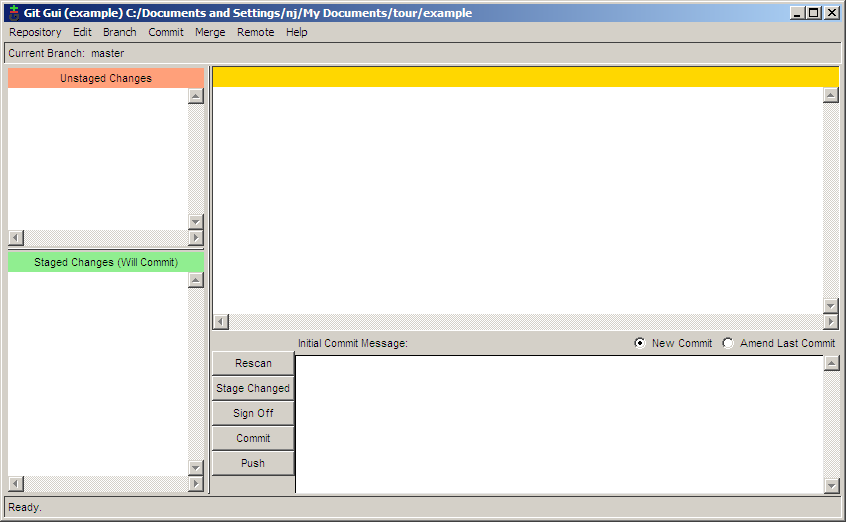

Create a new folder to start an empty project. Open the folder’s context menu and click “Git Create repository here”. This will add a “.git” folder to store Git’s data. At this point the repository is empty, the staging area is empty, all your project is in the working tree only and Git is not tracking anything. You can open Git Gui by clicking “Git GUI Here” in the folder’s context menu.

- Top-left shows unstaged changes (which at this point is all files)

- Bottom-left shows staged changes (empty)

- Top-right shows the diff for the selected file

- Bottom-right is where you can enter a commit message

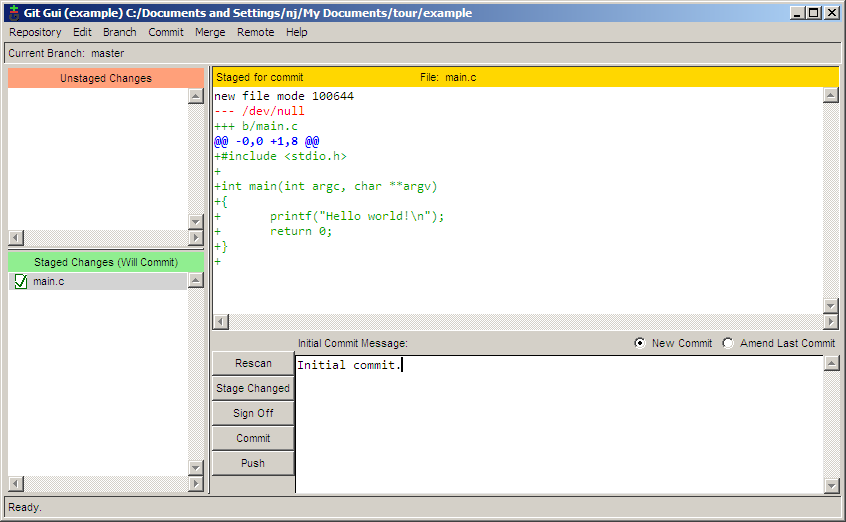

Now add a plain text file to your project folder and click the “Rescan” button in Git Gui. The file will show up in the top-left pane. The “Stage Changed” button will add all changed files to the staging area.

Tip: You can add individual files from the menu: Commit → Stage to commit.

Click “Stage Changed” to add your new file to the staging area and you will see it move from the top-left pane to the bottom-left pane. Now edit the file and save changes, then rescan again. The file now shows up in both the unstaged and staged panes. Clicking the file in the staged pane will show a diff on the right of the file contents when you staged it. Clicking the file in the unstaged pane will show the additional changes you made after staging it.

Tip: This can be useful for incrementally tracking changes while you code – even if you are not ready to make a commit, you can stage your changes and then do experimental code changes. You can see a diff of your changes so you know exactly what you changed and you can even back out your unstaged changes (Commit → Revert changes) while preserving your staged changes.

Let’s go ahead and make our first commit – rescan and click “Stage Changed”. Now enter a commit message in the lower right pane and click “Commit”. At this point the panes on the left are empty indicating that the working tree and the repository are in sync. If you delete all files (but not the “.git” folder!) in your working tree you can still restore them from the Git repository (which is stored in the”.git” folder).

If you make a commit and realize you want to make another small change and want to include that in the commit you can check the “Amend Last Commit” checkbox above the commit message. Be cautious with this feature as it rewrites history. Git history is the record of what was changed in each commit and what parent each commit has. Git is very good at enabling multiple developers to collaborate on a project and synchronize changes, but when you rewrite history this can affect other people and complicate things. If you have not shared your commit with anyone you can safely amend commits. Once you share a commit with others (e.g. by pushing to GitHub) then rewriting history (amend, rebase) will affect them as well.

Sharing your work

There are various ways of sharing Git repositories, some of the most popular are GitHub and GitLab. To share your repository on GitHub you will need a GitHub account and you need to create a new empty repository on GitHub. To connect your local repository with GitHub you will configure a new remote. In Git Gui this is done from the menu: Remote → Add. The location is the URL with “.git” appended to it. For example the Dojo repository is at https://github.com/dojo/framework and its Git location is https://github.com/dojo/framework.git. The name is arbitrary, but it is a common practice to name the primary remote “origin”. You can add more remotes, for example the primary remote would be under your organization and each developer might create “forks” (GitHub copies) of the project in their GitHub account. You would need a remote for “origin”, another remote for your own fork, and if you want to work with branches from other developers you would need a remote for them.

Tip: Git Gui makes it easy to add remotes, but if you want to manage them in more detail you can do so in TortoiseGit: choose “Git Sync” from the context menu and click the “Manage” button to the right of “Remote URL” at the top.

With a remote configured you can now upload your Git repository to GitHub with Git’s “push” command. In Git Gui the “Push” button is just below the “Commit” button. TortoiseGit gives you a little more control over how you push with its dialog in “Git Sync”. After successfully pushing your repository to GitHub you will be able to browse your files on GitHub.

Cloning and pulling from GitHub

We’ve just covered creating a local repository and pushing it to GitHub. What if you want to copy a repository from GitHub locally? Open the context menu of the folder that will be the project’s parent and click “Git Clone”. In the URL field enter the Git URL (e.g. https://github.com/dojo/framework.git). Everything else can be left as-is, but you can rename the folder if you want (by default the dojo/framework repo would be cloned into the “framework” folder, but you can change the name).

With a GitHub repository created, a local repository created, and the GitHub repository configured as a remote you can synchronize the two using the Pull and Push buttons in TortoiseGit’s “Git Sync” window. Pull will download changes from GitHub to your local repository; push will upload changes to GitHub.

Play well with others

Adding new features to a project is commonly done within a branch. A branch is a named group of commits. A Git repository starts with a single branch, typically named “master” or “main”. Branches can be temporary, where a feature is developed in a branch and eventually integrated into the main branch, or they can be long-lived to maintain multiple versions of a project. Let’s create a feature branch from “master” in Git Gui:

- Click Branch → Create

- Give your branch a name

- For “Starting Revision” accept the default of “Local branch: master”

- Click “Create”

That’s it! You are now on a new branch. Any commits you make will be in the branch, not in “master”. Git Gui displays the name of the current branch just below the menu bar. You can now make some commits and push your branch to GitHub using TortoiseGit: choose “Git Sync” from the context menu, then click the Push button. Work can continue in parallel on the main branch and feature branches, and when a feature branch is complete and ready to be integrated you create a pull request in GitHub.

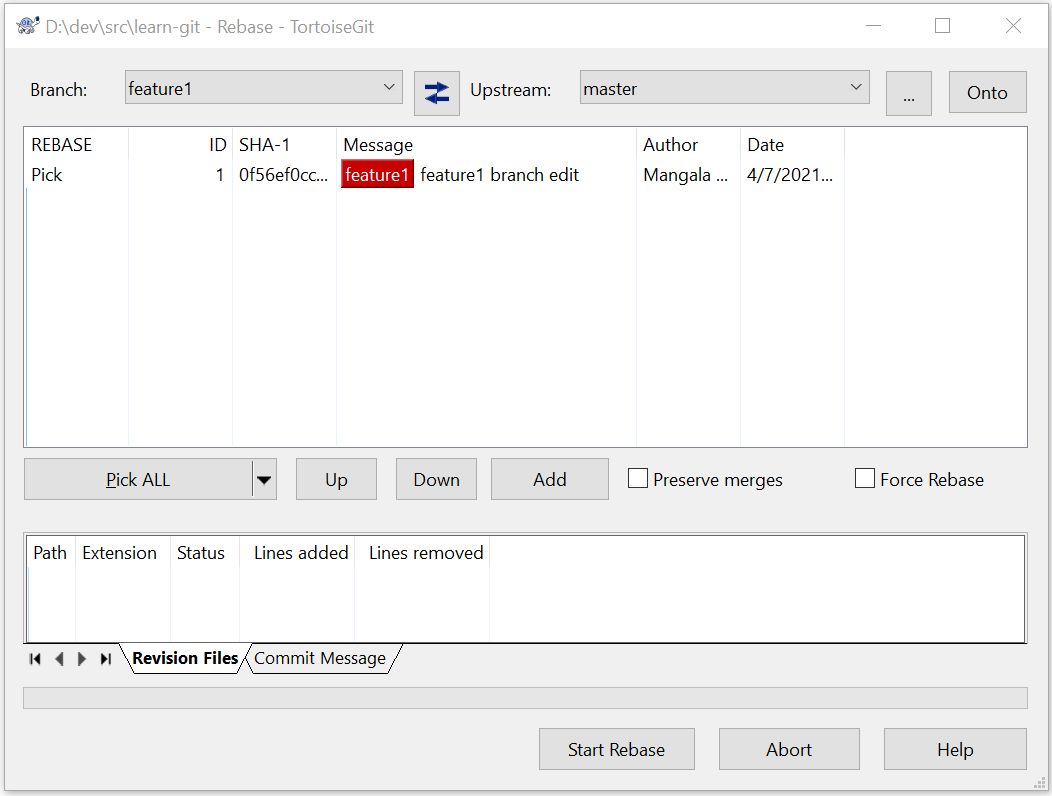

Rebasing a feature branch

Often when you are working on a feature branch work from other developers will be completed and merged into the main branch. Ideally work is broken up and scheduled in a way that minimizes conflicts, but they are inevitable.

One common workflow when integrating feature branches is to create a merge commit. A merge commit says “I added all these commits from this branch to master”, and potentially includes extra changes to resolve any conflicts. A merge workflow may be useful if you want your Git history to record who made what commits when, in what branch, and when they were merged. However, this type of history can be large and confusing. Many projects instead benefit from a history that records “this feature was added at this time by this person”.

Tip: A clean history makes finding out which commit broke (or fixed!) something with “git bisect” easier.

The recommended workflow to achieve a simple linear history is to use squash and rebase. Squashing a PR squashes all the PR’s commits into a single commit that is added to master directly (no extra merge commit). Rebasing is a method of resolving conflicts within a branch by rewriting the branch’s history. For a branch with commits C, D, and E, rebasing would change the commits (and assign new hashes) – this is why we say it “rewrites history”. The actual history is you created commits C, D, and E. When you rebase you change the history to record that you created commits C’, D’, and E’. The rebase commits will be identical if there are no conflicts, but will have a new parent. If there are conflicts you will have to resolve them during the rebase.

When should I rebase?

- If master has been updated with new code that you want to use in your branch

- If your PR has conflicts and cannot be merged

How to rebase

- Edit a file in your project to have 3 lines of text, save & commit to master

- Create a branch, edit line 3, save & commit

- Check out master, edit line 1, save & commit

- Check out your branch and look in the file – the most recent change to line 1 in master will not be present

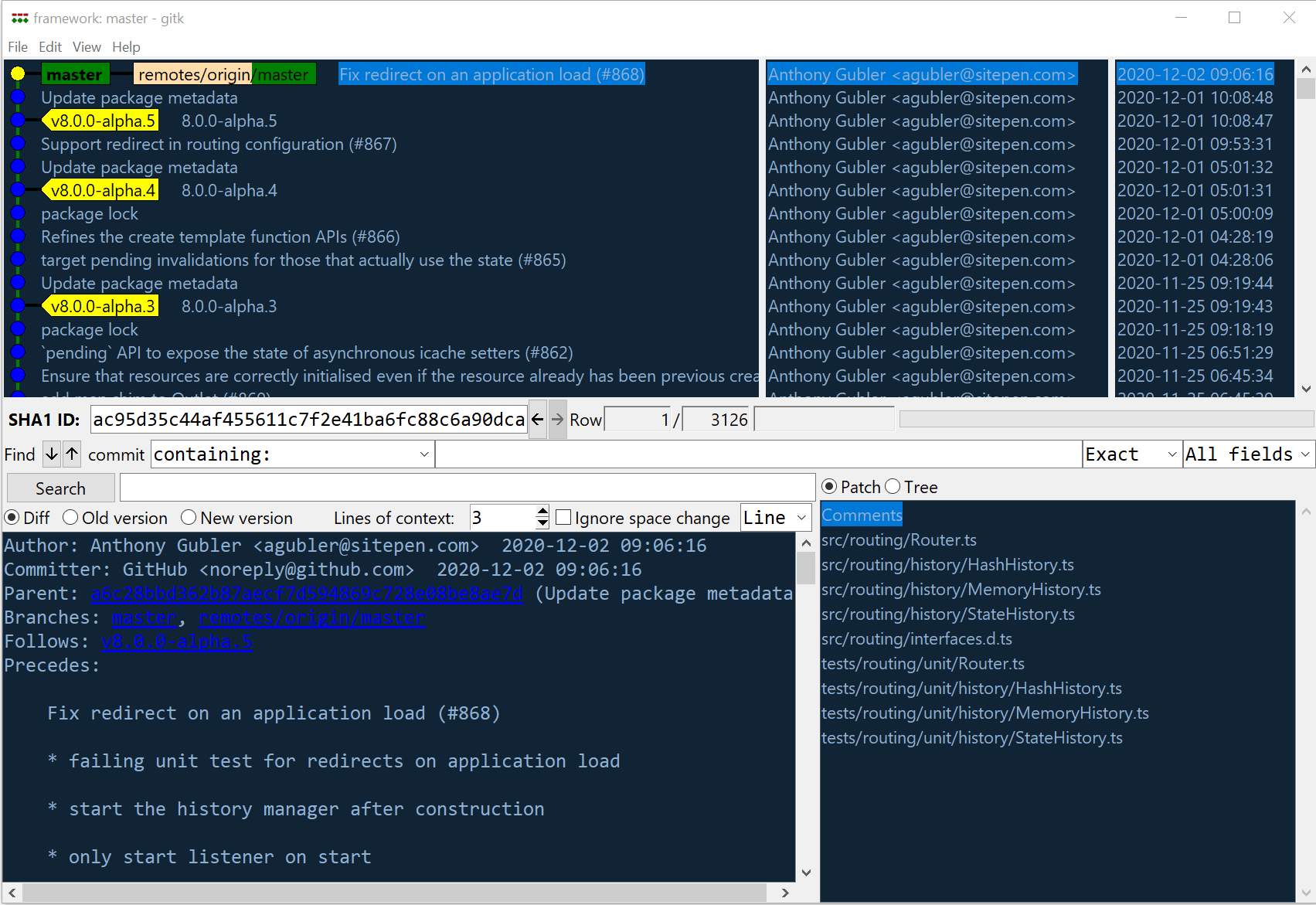

- In Git Gui click Repository → Visualize <branch>’s History

- This shows the commit history, click on a commit to see the SHA1 hash – note down the hash for your last commit

- Choose “Rebase” from TortoiseGit’s context menu

- Top left will show your branch

- In the top right set “Upstream” to “master”

- Click “Start Rebase” and “Done”

- Look at the branch history again – the commit to master has been inserted into the branch’s history, and your latest commit in the branch has a new hash

- History has been rewritten!

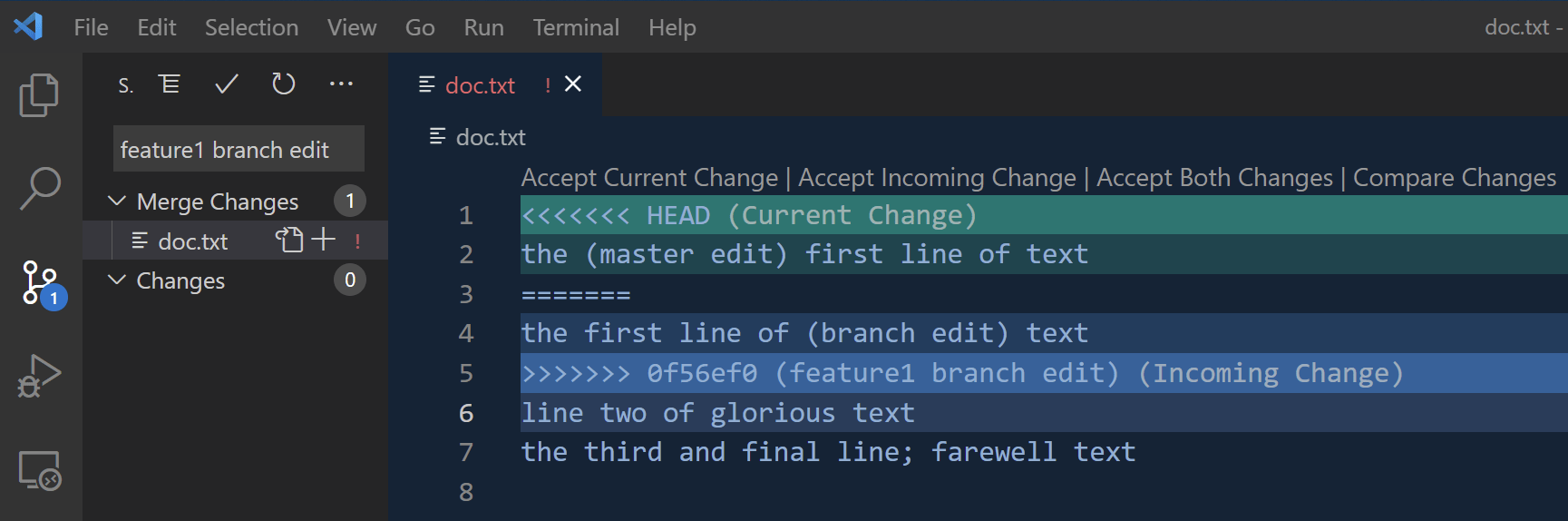

This was a simple rebase with no conflicts, let’s go through the process again with a conflict. You can continue with the same branch:

- Check out master, set line 1 to be “the first line of text”, save & commit

- Check out your branch, edit line 1 to be “the first line of (branch edit) text”, save & commit

- Check out master, set line 1 to be “the (master edit) first line of text”, save & commit

- Now when you rebase your branch on master the process halts indicating there is a conflict. VS Code provides a good UI for resolving conflicts, so open the project in VS Code and click the “Source Control” icon on the left.

- The left pane shows your files in two categories:

- Merge Changes: files with conflicts that cannot be automatically resolved (you need to fix these)

- Changes: files with no conflicts that can automatically be rebased (you don’t need to do anything)

- Open your file. VS Code will highlight conflicting lines, showing both versions of the line. “Current Change” is the value in the commit you are rebasing on (master). “Incoming Change” is the value in the commit in your branch. If one or the other is correct you can simply click “Accept Current/Incoming Change” in VS Code. If you need to manually edit the value you can click “Accept Both Changes” and edit the file as needed. When the conflict is resolved save the file and click the “Stage Changes” (➕) icon next to the file name.

- Back in TortoiseGit’s rebase dialog you can click “Resolved” in the file’s context menu and click “Commit” to finish rebasing.

As PRs are merged and the main branch is updated you may have to rebase your feature branch repeatedly to receive updates while continuing to work in your branch. If the updates to main do not affect your code there’s no need to rebase and incorporate them. When you create a PR on GitHub as long as there are no conflicts a squash merge will automatically squash and rebase all the commits in your PR into a single commit maintaining a linear history on master.

One challenge with rebasing is that the rebase process is performed for every commit in your branch. If you have a lot of commits, and a lot of noise in your change history (let’s do this, no that, hmmm, something else) then rebasing can be a bit of a waste of time resolving conflicts in commits that aren’t even relevant to the current state of the code. In this case you may benefit from squashing your whole branch to a single commit in a new branch. Then you move development to the new branch and when you rebase you are only dealing with a single commit.

Tip: Selective staging

Git Gui makes selective staging of individual lines very easy. Suppose you edited a file, made some changes and are ready to commit. But you have some debug statements, or unrelated feature changes in the file that you don’t want to commit. Looking at the diff in Git Gui you can select individual lines and click “Stage Line for Commit” – be sure to do this in pairs, as the diffing is done by line, not by word. When anything in a line is changed the diff records:

- Line x was removed (displays old content in red with a minus sign at the beginning)

- Line x was inserted (displays new content in green with a plus sign at the beginning)

So to stage a change to a single word in a line you have to stage both the removal and the insertion, which are displayed as two separate lines in the diff. If you only want to stage a few lines you can easily select them from the diff and stage them. Conversely, if you have a lot of changes and only want to exclude a few lines you can stage the whole file, then in the staged diff click “Unstage Line From Commit” for the relevant lines.

Git back to work

You now have a good foundation of Git principles and basic to intermediate tasks in some common Git GUIs to be able to get back to focusing on writing code while maintaining good collaboration practices. Some further items to learn about are cherry picking commits, squashing branches, and Git’s “bisect” command.

I recently started to use GIT as source code management system, and because i’m not made for commands written in console-like windows, i was looking for a guide on how to install and use the GIT Gui for Windows.

I found this guide written by nathanj here and i think it’s one of the easiest tutorials that i found on the web. You can find it here or on nathanj site.

An Illustrated Guide to Git on Windows

Table of Contents

- About

- Downloading PuTTY

- Installing Git

- Creating a Repository

- Committing

- Branching

- Merging

- Viewing History

- Pushing to a Remote Server

- Pulling from a Remote Server

- Conclusion

About

Note: This guide was written in early 2009. Some parts of it may be out of date. Good luck!

Using the instructions in this document, you can quickly and easily install git on Windows. In this guide, I will create a repository, make several commits, create a branch, merge a branch, search the commit history, push to a remote server, and pull from a remote server. The majority of this will be done using GUI tools.

Although this guide is targeted for use on Windows, the git gui tool works the same on all platforms. Because of this, git users on other platforms may find useful information here as well.

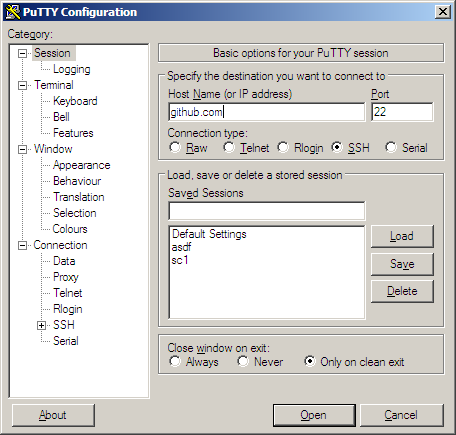

Downloading PuTTY

Although you can use the SSH program that comes with git, I prefer to use the PuTTY Agent to keep track of my SSH keys. If

you don’t already have them, download putty.exe, plink.exe, pageant.exe, and puttygen.exe from the PuTTY

web site.

Later in this guide, we will use these programs for securely pushing our changes to a remote server.

Installing Git

First, download msysgit.

This download is a single executable which installs the entire git system. While going through the installer, you will want to check the options to add Windows Explorer integration when you right click on a folder.

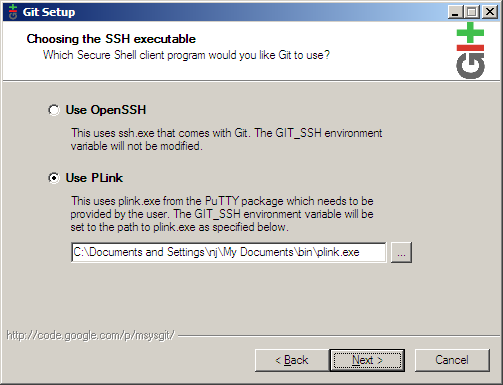

Because we will be using PuTTY as our SSH client, choose Use PLink and fill in the path to the downloaded plink.exe executable.

Continue clicking Next until the installation is complete.

Creating a Repository

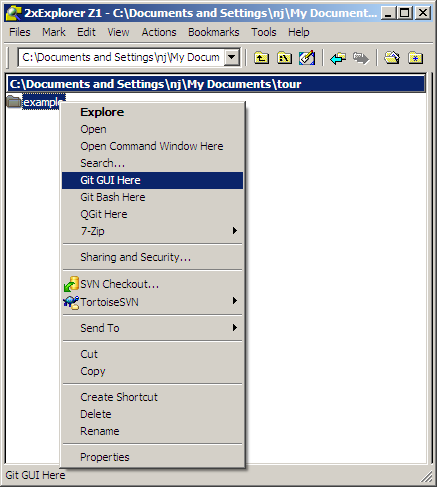

To create a repository, first create the folder you want the project to live under. Next, right click on the folder and choose Git GUI Here. Because there is no git repository in this folder yet, you will be presented with the git gui startup dialog.

Choosing Create New Repository brings us to the next dialog.

Fill in the path to your new directory and click Create. You will then be presented with the main interface of git gui, which

is what will be shown from now on when you right click on your folder and click Git GUI Here.

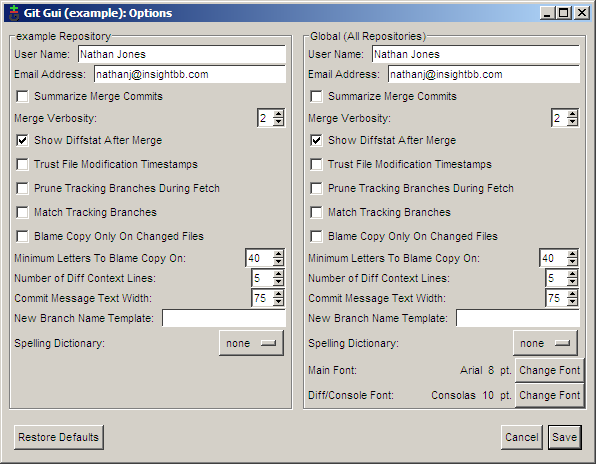

Now that the repository has been set up, you will need to tell git who you are so that commit messages will have the correct author. To do this, choose Edit ? Options.

In the options dialog, there are two versions of each preference. On the left side of the dialog are options that you want for this repository only, while the right side contains the global options which apply to all repositories. The defaults for these options are sensible so just fill in the user name and email for now. If you have a favorite font, you may want to set it now as well.

Committing

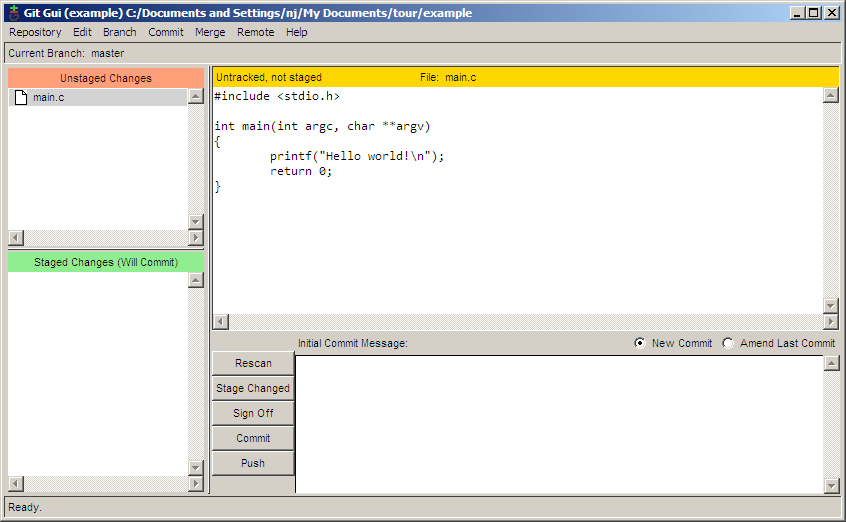

Now that the repository has been created, it is time to create something to commit. For this example, I created a file called main.c with the following content:

#include

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

printf("Hello world!\n");

return 0;

}

Clicking the Rescan button in the git gui will cause it to search out new, modified, and deleted files in the directory. In the next screenshot, git gui has found our new file (amazing, I know).

To add the file for committing, click the icon to the left of the filename. The file will be moved from the Unstaged Changes pane to the Staged Changes pane. Now we can add a commit message and commit the change with the Commit button.

Saying hello to the world is all well and good, but I would like my program to be more personal. Let’s have it say hello to the user. Here’s my code for that:

#include

#include

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char name[255];

printf("Enter your name: ");

fgets(name, 255, stdin);

printf("length = %d\n", strlen(name)); /* debug line */

name[strlen(name)-1] = '\0'; /* remove the newline at the end */

printf("Hello %s!\n", name);

return 0;

}

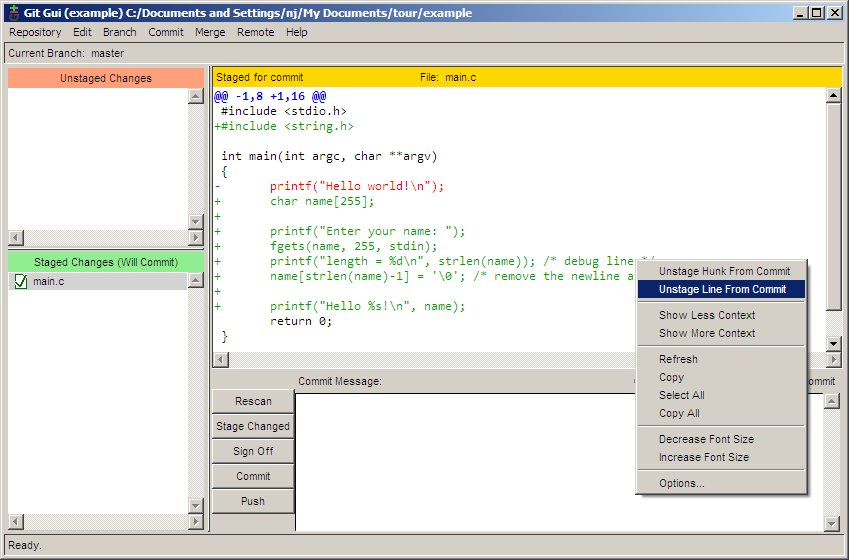

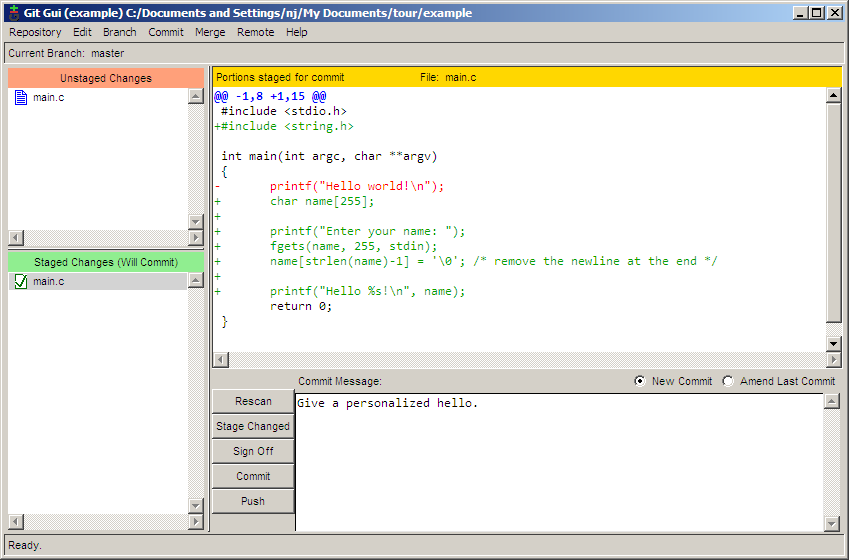

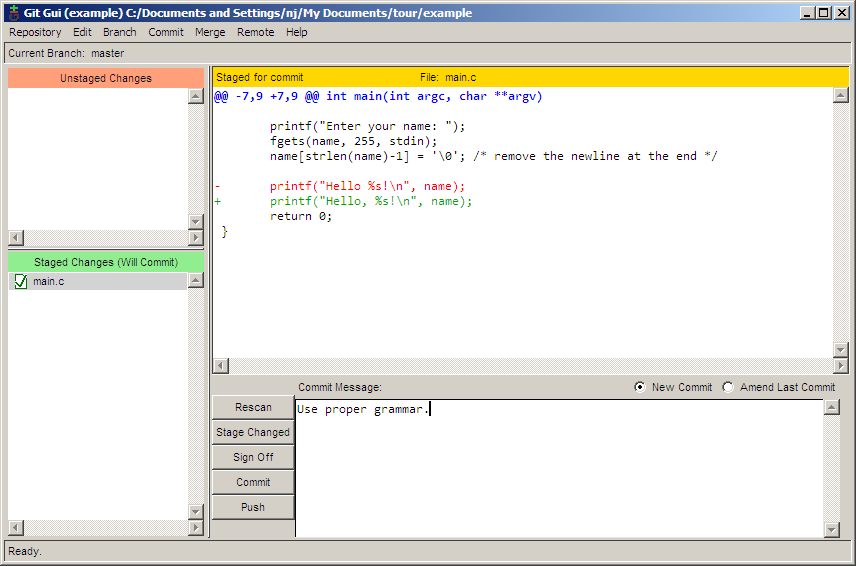

I had some trouble figuring out why a newline was printed after the user’s name, so I added a debugging line to help me track it down. I would like to commit this patch without the debug line, but I want to keep the line in my working copy to continue debugging. With git gui, this is no problem. First, click Rescan to scan for the modified file. Next, click the icon to the left of the filename to stage all modifications for commit. Then, right click on the debug line and chose Unstage Line From Commit.

Now, the debug line has been unstaged, while the rest of the changes have been staged. From here, it is just a matter of filling in the commit message and clicking Commit.

Branching

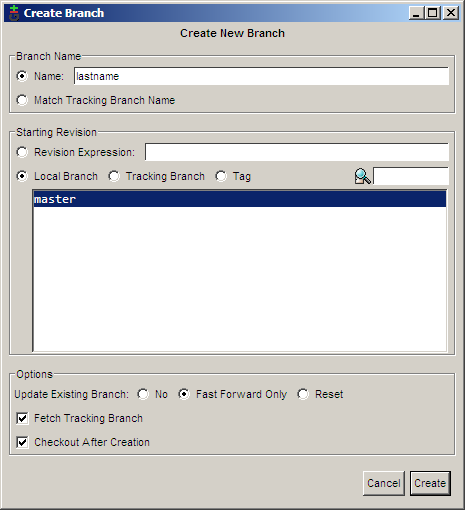

Now let’s say that we want to start adding new features for our next big version of the program. But, we also want to keep a stable, maintenance version of the program to fix bugs on. To do this, we will create a branch for our new development. To create a new branch in git gui, choose Branch ? Create. The big feature that I would like to add is to ask the user for their last name, so I am calling this branch lastname. The default options in the Create Branch dialog are all fine, so just enter the name and click Create.

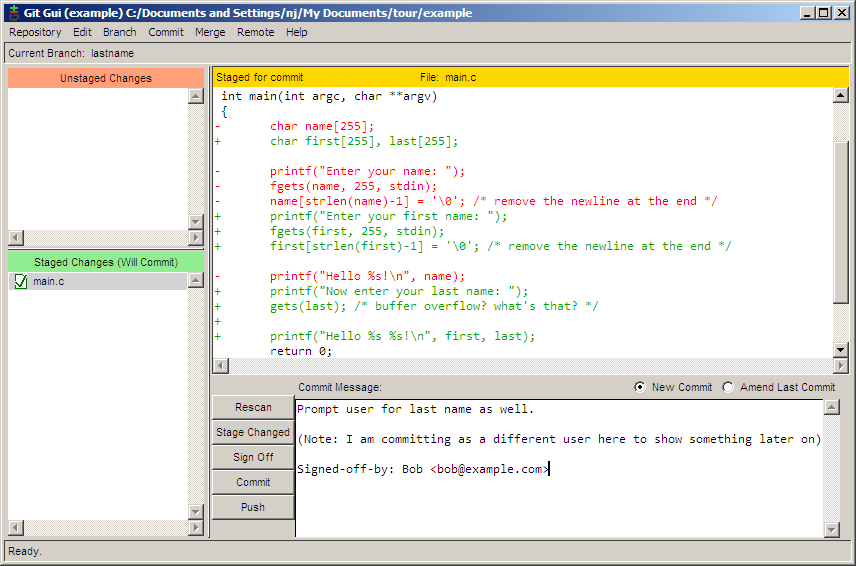

Now that I am on the lastname branch, I can make my new modifications:

#include

#include

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char first[255], last[255];

printf("Enter your first name: ");

fgets(first, 255, stdin);

first[strlen(first)-1] = '\0'; /* remove the newline at the end */

printf("Now enter your last name: ");

gets(last); /* buffer overflow? what's that? */

printf("Hello %s %s!\n", first, last);

return 0;

}

And then I can commit the change. Note here that I am committing using a different name. This is to show off something later. Normally you would always use the same name when committing.

Meanwhile, a user informs us that not displaying a comma when directly addressing someone is a serious bug. In order to make

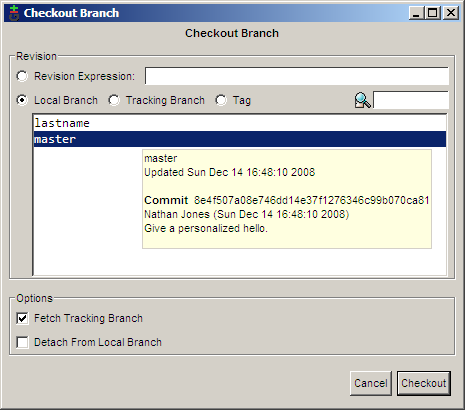

this bug fix on our stable branch, we must first switch back to it. This is done using Branch ? Checkout.

Now we can fix our major bug.

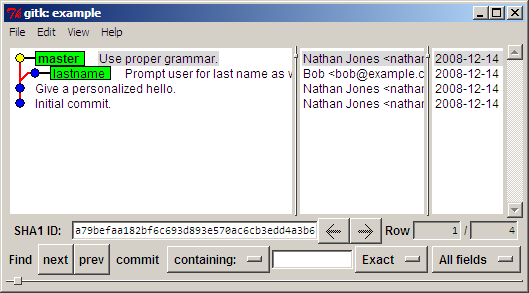

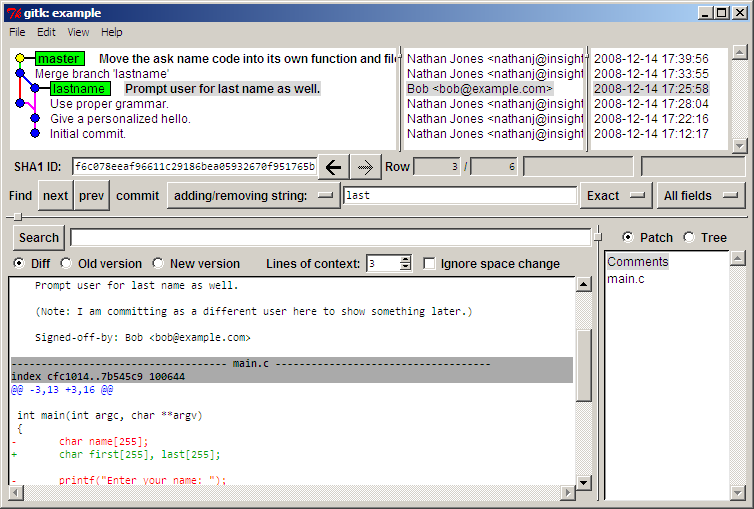

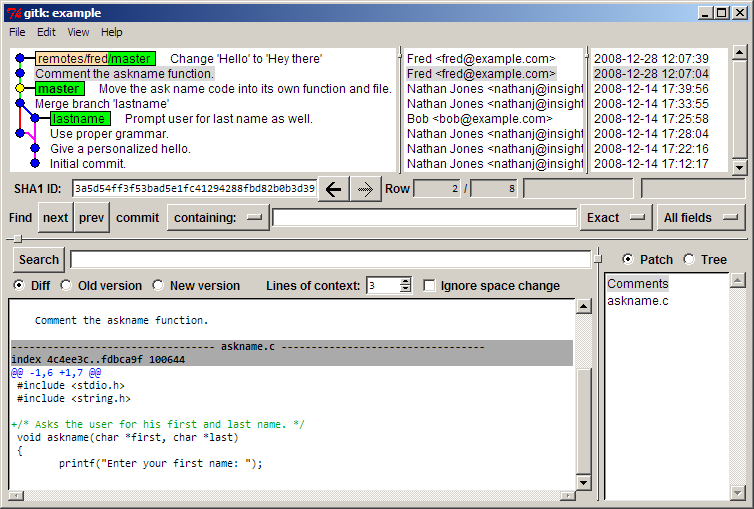

If we choose Repository ? Visualize All Branch History, we can see how our history is shaping up.

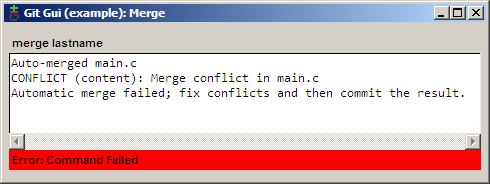

Merging

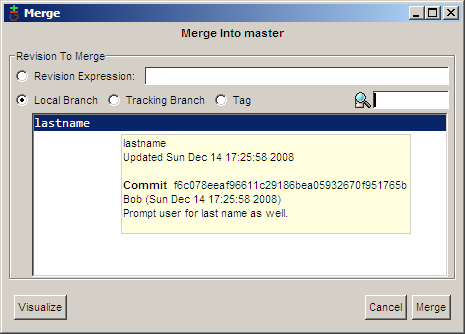

After days of work, we decide that our lastname branch is stable enough to be merged into the master branch. To perform the merge, use Merge ? Local Merge.

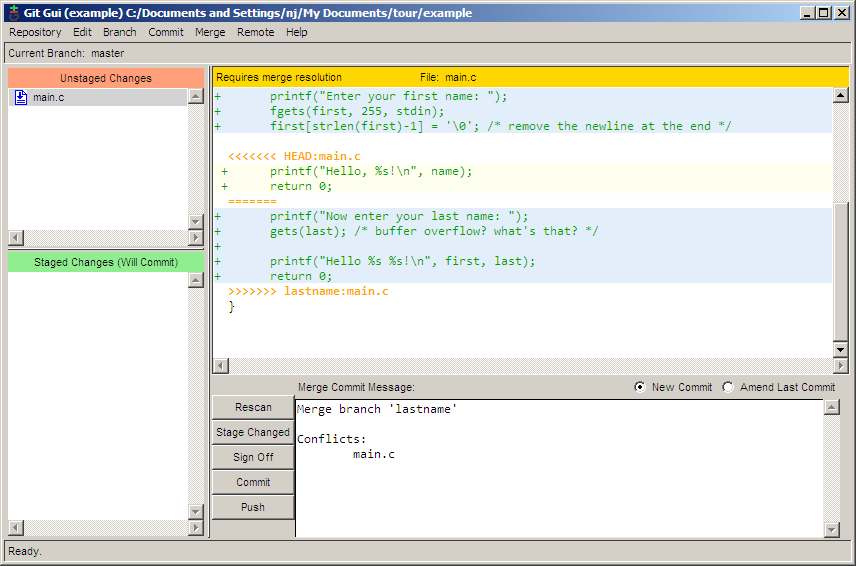

Because the two different commits made two different

modifications to the same line, a conflict occurs.

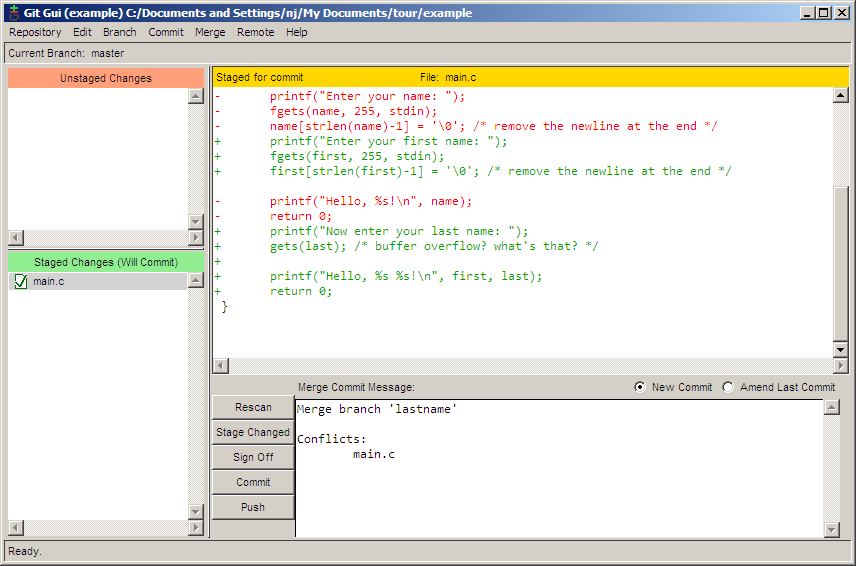

This conflict can be resolved using any text editor. After resolving the conflict, stage the changes by clicking the file icon and then commit the merge by clicking the Commit button.

Viewing History

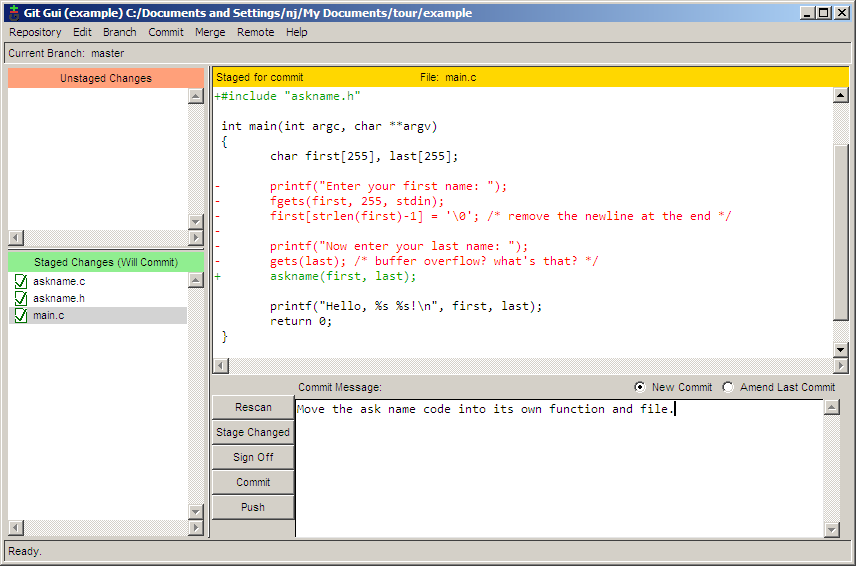

The main.c file is starting to get a bit big, so I decided to move the user prompting portion of the code into its own function. While I was at it, I decided to move the function into a separate file. The repository now contains the files main.c, askname.c, and askname.h.

/* main.c */

#include

#include "askname.h"

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char first[255], last[255];

askname(first, last);

printf("Hello, %s %s!\n", first, last);

return 0;

}

/* askname.c */

#include

#include

void askname(char *first, char *last)

{

printf("Enter your first name: ");

fgets(first, 255, stdin);

first[strlen(first)-1] = '\0'; /* remove the newline at the end */

printf("Now enter your last name: ");

gets(last); /* buffer overflow? what's that? */

}

/* askname.h */

void askname(char *first, char *last);

The history of the repository can be viewed and searched by choosing Repository ? Visualize All Branch History.

In the next screenshot, I am trying to find which commit added the last variable by searching for all commits which added or removed the word last. Commits which match the search are bolded, making it quick and easy to spot the desired commit.

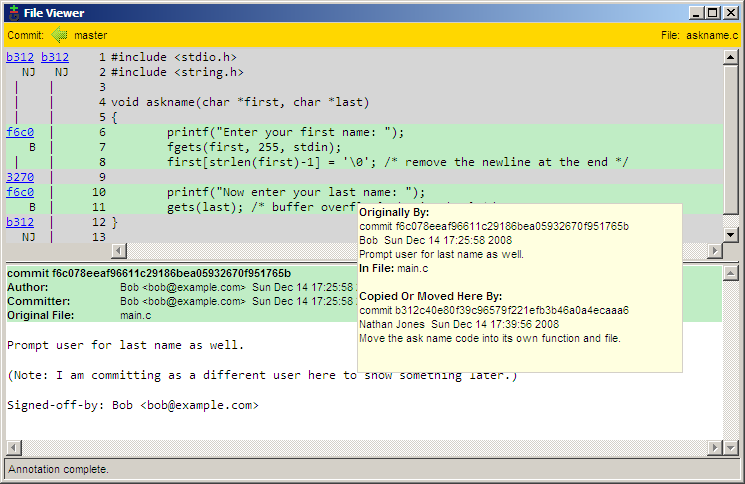

A few days later, someone looks through our code and sees that the gets function could cause a buffer overflow. Being the type to point fingers, this person decides to run a git blame to see who last modified this line of code. The problem is that Bob is the one who committed the line, but I was the one who last touched it when I moved the line into a different file. Obviously, I am not to blame (of course). Is git smart enough to figure this out? Yes, it is.

To run a blame, select Repository ? Browse master’s Files. From the tree that pops up, double click on the file with the line in question which in this case is askname.c.

Hovering the mouse over the line in question shows a tooltip message that tells us all we need to know.

Here we can see that the line was last modified by Bob in commit f6c0, and then I moved it to its new location in commit b312.

Pushing to a Remote Server

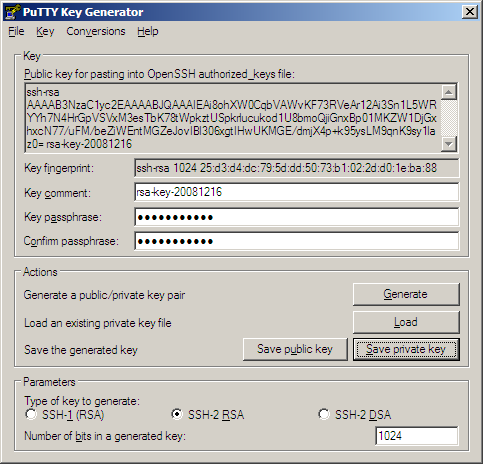

Before pushing to a remote server, you must first create a SSH public and private key pair. By using SSH, you will be able to securely authenticate to the server that you are who you say you are. Creating the key pair is a simple process. Begin by running the puttygen.exe program downloaded earlier. Next, click the Generate button to generate the keys. After processing for a few seconds, click the Save private key button to save your new private key. Copy the public key to the clipboard in preparation for the next step. I would recommend not clicking the Save public key button because the saved file is in a non-standard

format; trying to use it with other software might be problematic.

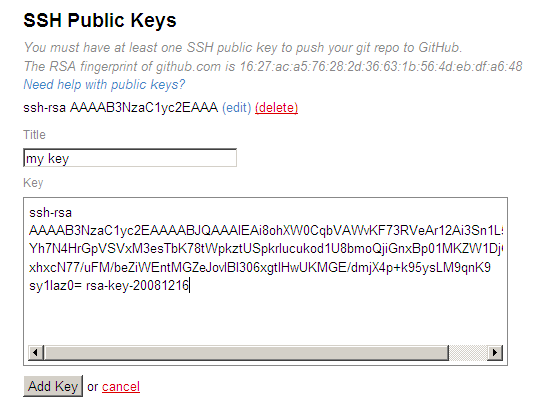

Now that the keys are generated, the remote servers need to know about it. If you would like to use github to host your code, just

go to your account page and paste in the public key.

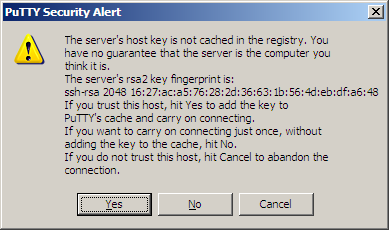

Now github has our public key, but we do not yet have github’s. To remedy this, launch putty.exe, connect to github.com, and click Yes to accept github’s public key. You can safely close the login window that opens up after accepting the key.

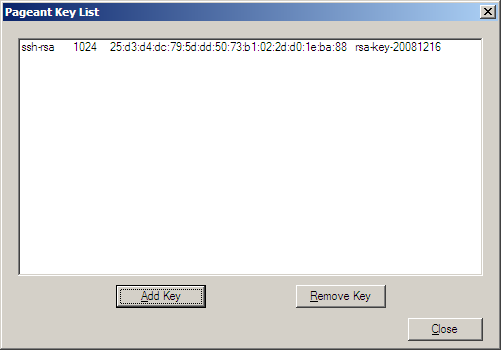

We need our private key to be loaded up to use with our public key, so launch pageant.exe. This program will create an icon in your system tray. Double clicking on the icon will open up a window into which the private key can be added. Once the private key is added, the agent will sit in the background and provide authentication when needed.

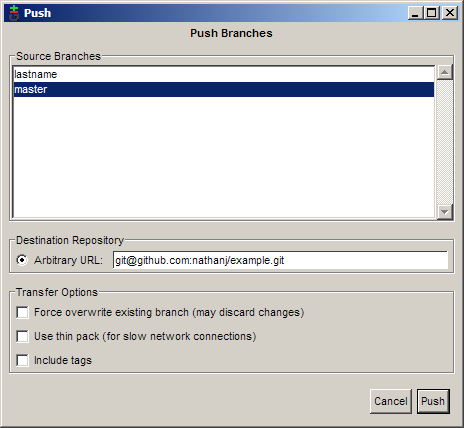

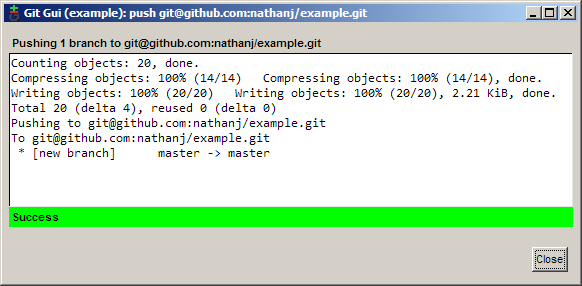

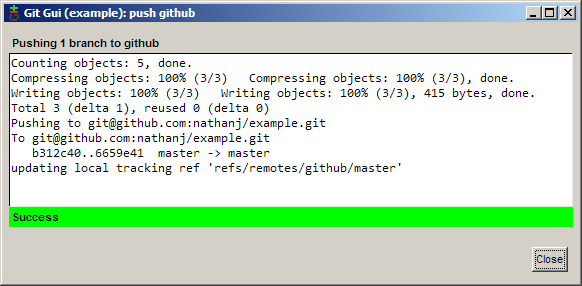

Now that our client and server can authenticate each other, it is time to push! Remote ? Push will open up the push dialog. Typing in the commit address for the project and clicking Push will send the changes on their way.

Of course, typing in the remote url would become quite annoying if we had to do it with every push. Instead, git allows us to alias the long urls using remotes. Git gui currently does not have a way to add a remote, so the command line must be used. Right click on the repository folder and choose Git Bash Here.

In the prompt, enter the following command:

git remote add github git@github.com:nathanj/example.git

Note: After adding a remote, close and reopen git gui for it to recognize the new remote.

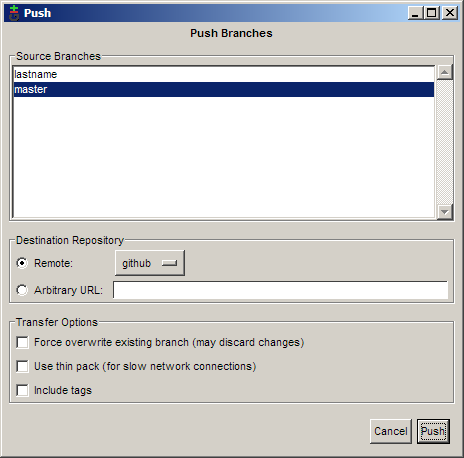

Now the remote github is aliased to the url git@github.com:nathanj/example.git. When viewing the push dialog in git gui, a convenient drop down list of remotes is shown.

Pulling from a Remote Server

Because our code is so useful, dozens of people have downloaded and now use our program. One person in particular, Fred, has decided to fork our project and add his own commits.

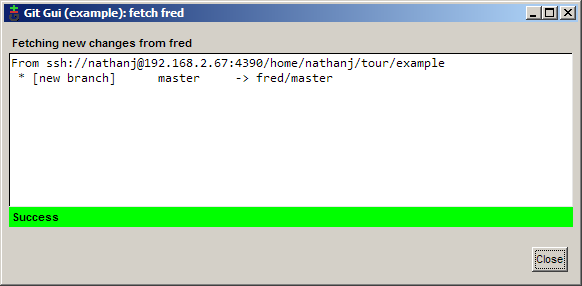

Now that he’s added his code, he would like us to pull those commits from him into our repository. To do this, first create another remote.

git remote add fred ssh://fred@192.168.2.67/home/fred/example

Now we can fetch Fred’s changes using Remote ? Fetch

from ? fred.

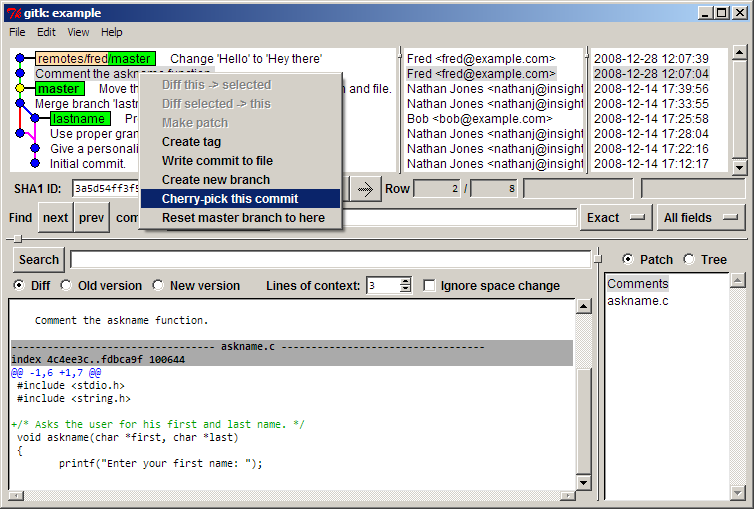

After the fetch, Fred’s commits have now been added to our local repository under the remotes/fred/master branch. We can use gitk to visualize the changes that Fred has made.

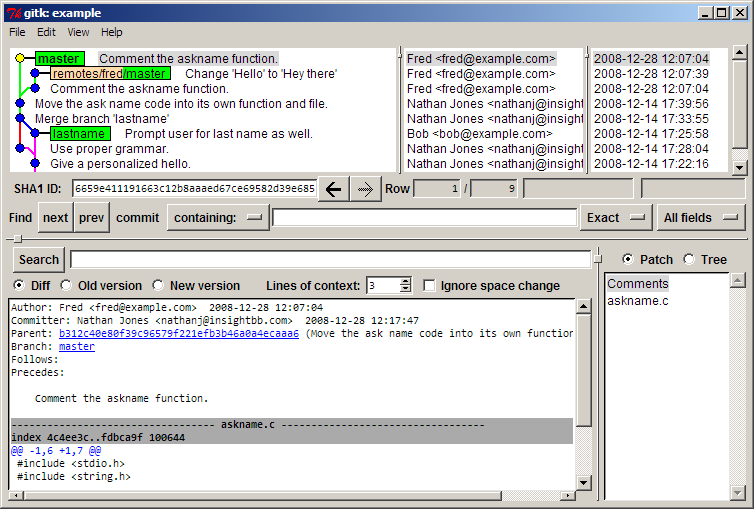

If we like all of Fred’s changes, we could do a normal merge as before. In this case though, I like one of his commits but not the other. To only merge one of his commits, right click on the commit and choose Cherry-pick this commit. The commit will then be merged into the current branch.

We can now push a final time to send Fred’s patch to our

github tree for everyone to see and use.

Conclusion

In this guide, I have shown how to do many common tasks in git using GUI tools. I hope that this guide has shown that it is not only possible but easy to use git on Windows without having to use the Windows shell for most operations.

Git is a powerful and widely used version control system. It provides a graphical user interface (GUI) that makes it easier for beginners to use Git. In this guide, we will discuss how to start Git-GUI and provide a quick overview of its functionalities.

To start Git-GUI, you need to ensure it’s installed on your system. You can install it using the appropriate commands for your operating system. Once installed, you can start Git-GUI by running the «git gui» command in your terminal. Git-GUI provides a graphical interface for managing Git repositories, allowing you to stage changes, create commits, and push changes to a remote repository.

- What is Git-GUI?

- Installing Git-GUI

- Starting Git-GUI

- Using Git-GUI

- Conclusion

What is Git-GUI?

Git-GUI is a portable graphical interface for Git. It’s designed to allow users to make changes to their repositories using a visual interface, which can be helpful for those who are not comfortable with command-line interfaces. Git-GUI provides a simple and intuitive way to stage changes, create commits, and push changes to a remote repository.

Installing Git-GUI

Before we can start Git-GUI, we need to ensure that it’s installed on our system. Depending on your operating system, the installation process may vary.

For Ubuntu and other Debian-based systems, you can install Git-GUI using the following command in your terminal:

sudo apt-get install git-guiFor Mac users, Git-GUI comes pre-installed with Git. If you’ve installed Git, you should already have access to Git-GUI.

For Windows users, Git-GUI is included in the Git for Windows package, which can be downloaded from the official Git website.

Starting Git-GUI

Once Git-GUI is installed, you can start it by running the following command in your terminal:

git guiThis command will open the Git-GUI interface, where you can start managing your Git repositories.

Using Git-GUI

Git-GUI provides a number of functionalities that make it easier to manage your Git repositories. Here are some of the key functionalities:

- Creating a New Repository: You can create a new repository by selecting the ‘Create New Repository’ option from the ‘Repository’ menu.

- Cloning a Repository: To clone an existing repository, select the ‘Clone Existing Repository’ option from the ‘Repository’ menu.

- Staging Changes: You can stage changes by selecting the files you want to stage and clicking on the ‘Stage Changed’ button.

- Creating Commits: Once you’ve staged your changes, you can create a commit by entering a commit message and clicking on the ‘Commit’ button.

- Pushing Changes: To push your changes to a remote repository, select the ‘Push’ option from the ‘Remote’ menu.

Conclusion

Git-GUI is a powerful tool that makes it easier to manage your Git repositories. By providing a visual interface, it allows users to perform key Git operations without having to use the command line. Whether you’re a beginner just starting out with Git, or an experienced developer looking for a more convenient way to manage your repositories, Git-GUI is a valuable tool to have in your toolkit.

Yes, Git-GUI is available for Windows and can be downloaded as part of the Git for Windows package from the official Git website.

Yes, Git-GUI is pre-installed with Git on Mac. If you’ve installed Git, you should already have access to Git-GUI.

Yes, Git-GUI is available for Linux. On Ubuntu and other Debian-based systems, you can install Git-GUI using the command sudo apt-get install git-gui in the terminal.

Yes, you can create a new repository by selecting the ‘Create New Repository’ option from the ‘Repository’ menu in Git-GUI.

Yes, you can clone an existing repository by selecting the ‘Clone Existing Repository’ option from the ‘Repository’ menu in Git-GUI.

To stage changes, you can select the files you want to stage and click on the ‘Stage Changed’ button in Git-GUI.

Once you’ve staged your changes, you can create a commit by entering a commit message and clicking on the ‘Commit’ button in Git-GUI.

To push your changes to a remote repository, you can select the ‘Push’ option from the ‘Remote’ menu in Git-GUI.

Yes, Git-GUI can be used alongside the command line. You can switch between the two as per your preference and requirements.

Yes, Git-GUI is designed to be beginner-friendly and provides a visual interface that makes it easier for beginners to use Git. It can be a great starting point for those who are not comfortable with the command line.